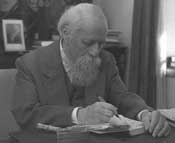

Martin Buber

(1878 - 1965)

Martin Buber was born in Vienna in

1878. He lived for a period of time with his grandfather, Solomon Buber, a

famous midrash scholar. Powerfully influenced by Ahad

HaAm, he was a member of the Third

Zionist Congress in 1899.

When he was 26, Buber began

studying Chassidic texts and was greatly moved by their spiritual message.

During World War I, he founded the

Jewish National Committee, which worked at helping Eastern European

Jews suffering under Axis domination.

Buber was a utopian Zionist.

He believed strongly that the most important possibility for Zionism

was in changing the relationships between people. He wrote powerfully

in favor of Arab rights in Palestine. Even in later years, he worked

for the establishment of a joint Arab-Jewish state. Obviously, he

failed

In 1938, Buber settled in Palestine

and was a professor of philosophy at Hebrew University. He died in

1965.

Martin Buber is best-known for his

book I

and Thou, which he wrote in 1923. It focused on the way

humans relate to their world. According to Buber, frequently we view

both objects and people by their functions. Doing this is sometimes

good: when doctors examine us for specific maladies, it's best if

they view us as organisms, not as individuals. Scientists can learn a

great deal about our world by observing, measuring, and examining.

For Buber, all such processes are I-It relationships.

Unfortunately, we frequently view

people in the same way. Rather than truly making ourselves completely

available to them, understanding them, sharing totally with them,

really talking with them, we observe them or keep part of ourselves

outside the moment of relationship. We do so either to protect our

vulnerabilities or to get them to respond in some preconceived way,

to get something from them. Buber calls such an interaction I-It.

It is possible, notes Buber, to

place ourselves completely into a relationship, to truly understand

and "be there" with another person, without masks,

pretenses, even without words. Such a moment of relating is called

"I-Thou." Each person comes to such a relationship without

preconditions. The bond thus created enlarges each person, and each

person responds by trying to enhance the other person. The result is

true dialogue, true sharing.

Such I-Thou relationships are not

constant or static. People move in and out of I-It moments to I-Thou

moments. Ironically, attempts to achieve an I-Thou moment will fail

because the process of trying to create an I-Thou relationship

objectifies it and makes it I-It. Even describing the moment

objectifies it and makes it an I-It. The most Buber can do in

describing this process is to encourage us to be available to the

possibility of I-Thou moments, to achieve real dialogue. It can't be

described. When you have it, you know it. Buber maintains that it is

possible to have an I-Thou relationship with the world and the

objects in it as well. Art, music, poetry are all possible media for

such responses in which true dialogue can take place.

Buber then moves from this

existential description of personal relating to the religious

experience. For Buber, God is the Eternal Thou. By trying to prove

God's existence or define God, the rationalist philosophers

automatically established an I-It relationship. This is Buber's major

problem with Hermann

Cohen.

Like a person we love, we can't

define God; we can't set up preconditions for the relationship. We

simply have to be available, open to the relationship with the

Eternal Thou. And when we experience such an I-Thou relationship, the

moment doesn't need words. In fact, the most intense moments we

experience with another person take place without words. Nor is the

intensity of the experience significant. Buber wasn't encouraging

mystical moments. The I-Thou relationship changed the sharers, but it

did so naturally, sometimes almost imperceptibly. For Buber, it is

possible to have an I-Thou relationship with God through I-Thou

moments with people, nature, art, the world.

Finally, Buber offers us a Jewish

insight into the I-Thou relationship. After our redemption from

Egypt, we as a people encountered God. We were available and open,

and the Sinai moment was an I-Thou relationship for an entire people

and for each individual. The Torah, the prophets, and our rabbinic

texts were all written by humans expressing the I-Thou relationship

with the Eternal Thou. By reading those texts and being available to

the relationship inherent in them, it is also possible for us to make

ourselves available for the I-Thou experience with the Eternal Thou.

We must come without precondition, without expectation because that

would already attempt to limit our relationship partner, God, and

thus create an I-It moment. If we try to analyze the text, we again

create an I-It relationship because analysis places ourselves outside

of the dialogue, as an observer and not a total participant.

For Buber, to do an action because

it has been previously legislated is meaningless. Only our response

at the moment of I-Thou can have meaning. Because of that premise,

Buber disagreed with Rosenzweig over the importance of traditional

practice in daily life. It was enough to respond to the I-Thou

encounter in whatever individualized way the moment created.

Sources: Gates

to Jewish Heritage |