Source: Based on Central Bureau of

Statistics data.

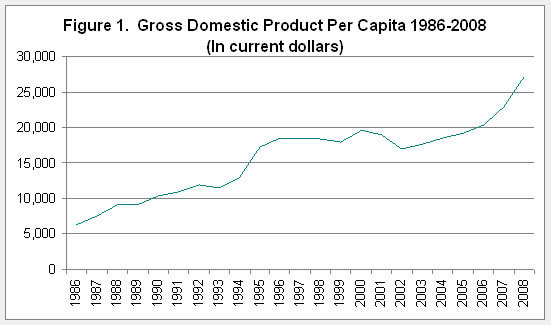

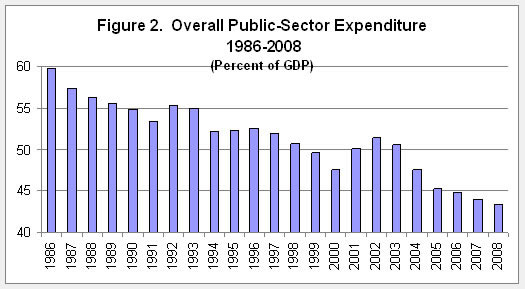

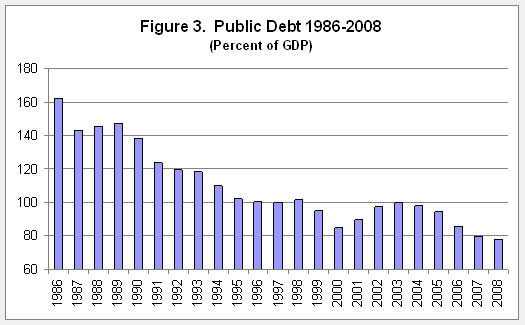

In retrospect,

the increase in fiscal discipline, which was characterized by a substantial

reduction in both public spending (from about 60% of GDP in the mid- 1980s to

about 43% by the end of 2008) and public debt (from about 163% of GDP to about

78% in 2008), was primarily the result of a substantial reduction in defense

expenditure – from more than 20% of GDP in the mid-1980s to less than 10%

recently. This reduction was made possible by, among other things, peace

agreements with Egypt and Jordan.

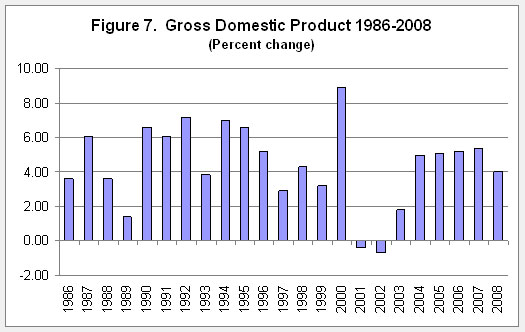

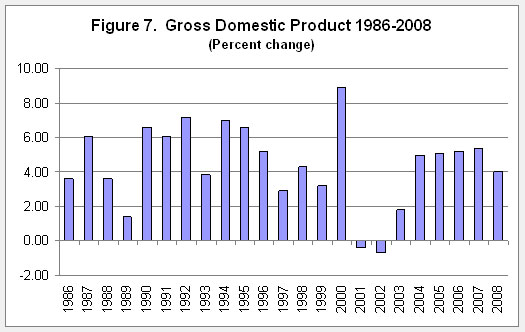

The introduction

of the Stabilization Plan in 1985 led to a drastic reduction in the public

sector deficit – from some 14% of GDP prior to the imposition of the

Stabilization Plan (in 1984) to surpluses during the three subsequent years

and, later on, to deficits of significantly lower magnitudes, which resulted in

a gradual reduction of public debt. The first two years after the introduction

of the Stabilization Plan were characterized by a rise in GDP, a stable level

of employment and a balanced government budget, although there was also an

increase in the level of unemployment during this period, primarily due to the

efficiency measures in the business sector. The years 1988 and 1989 were

characterized by an economic downturn as the business sector adapted to the new

economic reality following the success of the Stabilization Plan. This

included, among other things, the restructuring of the Koor conglomerate, the

termination of the Lavi jet fighter project and the outbreak of the first

intifada.

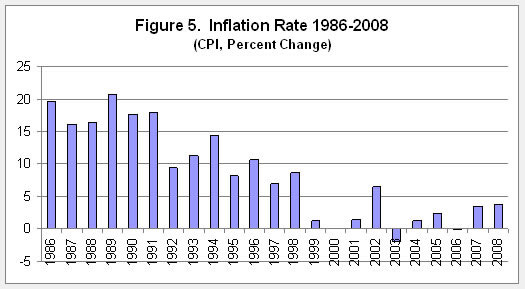

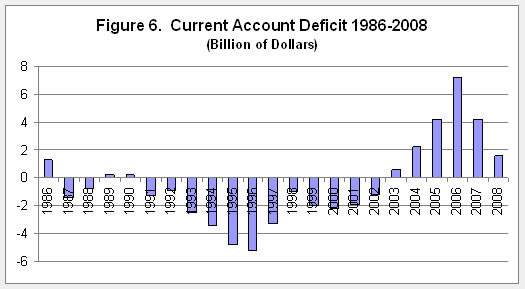

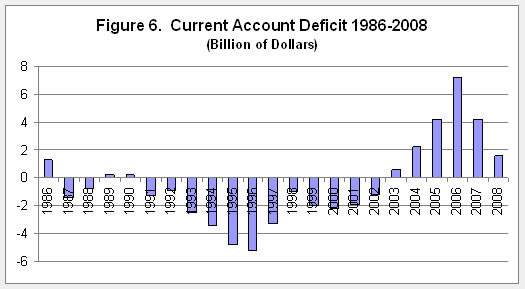

In sum, the

Stabilization Plan succeeded in achieving its two objectives: Reducing inflation to a rate of around 20%

and a significant reduction in the current account deficit. This success was supported

by the U.S. grant in the amount of $1.5 billion (over a two-year period).

Source: Based on Central Bureau of

Statistics data.

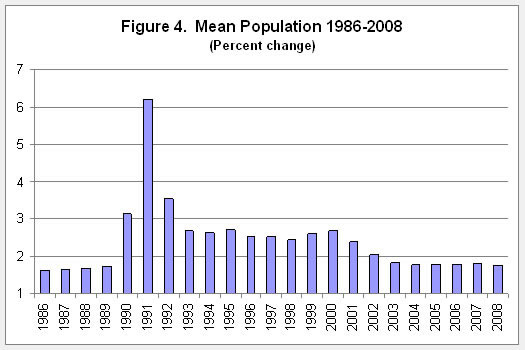

The beginning of

the 1990s was characterized both by a massive wave of immigration from the

Soviet Union and by the globalization process, which intensified during the

subsequent two decades. At the same time, the Israeli economy was becoming

increasingly open and this paved the way for the major reforms implemented

during the 1990s. These included the Deficit Reduction Law, an increasingly

flexible exchange rate regime following the transition from a horizontal

exchange rate band to a diagonal band. Also included was the transition to an

inflation targeting regime, a policy of exposing the economy to foreign trade

with countries that were not included within the framework of the trade

agreements with the U.S. and the European bloc (particularly Asian countries),

a reform of the capital market and the end of segmentation in the credit

market.

The wave of

immigration had a number of effects on the economy: Domestic demand increased

dramatically, which led to accelerated economic growth and a sharp increase in

investment. The massive immigration was also characterized by a high level of

human capital, which created the basis for a major increase in the size of the

more advanced industries and led to accelerated development in the hi-tech

industries, particularly from the mid-1990s onward. The considerable growth in the population brought

about a sharp rise in the rate of unemployment, primarily during the years

1991-1993, alongside a downward trend in real wages and an increasingly

competitive labor market accompanied by a decline in the influence of the Histadrut in the market. During the second half of the 1990s, once immigrants

had been absorbed into the labor force, the rate of unemployment declined to

levels that prevailed prior to the wave of immigration (between 6–7%).

At the beginning

of the 1990s, a global downtrend in prices began and, therefore, exchange rates

were made more flexible with the adoption of a regime with a long-term

commitment to inflation targets and a more flexible exchange rate policy. During the period 1992–1994, inflation

decreased from a plateau of around 20% to 10%. Nevertheless, there were

temporary fluctuations due to a number of geopolitical events, such as the

weakening of the Arab boycott, the Oslo Accords with the Palestinians in 1993

and the peace agreement with Jordan in October 1994.

This drop to a

new plateau was the result of a number of factors, including the effect of the

wave of immigration on the labor market (mainly through a reduction in wages),

a reduction in the dollar prices of imports, a supply surplus in the housing

market that reflected a significant reduction in demand, an increase in the

interest rate and, finally, the passing of the Deficit Reduction Law. This law

was introduced following, among other things, the increase in the deficit as a

result of the wave of immigration and the desire to signal to the public that

the government had not abandoned the objective of deficit reduction. During the

period 1994–1995, however, following an extended timeframe in which there were

no significant changes in labor agreements, it was decided to award a

substantial wage increase to public sector employees, a move that undermined to

a large extent the policy commitment to reduce the government deficit.

In parallel to

the adoption of the Deficit Reduction Law, the government decided, at the end

of 1991, to adhere to a trajectory for reducing the rate of inflation by

adopting an inflation-targeting regime. The main strategy of the Bank of Israel

during this period was to maintain a non-inflationary environment while

lowering the interest rate as much as possible to support real economic

activity. In implementing this strategy, there was also a need to ensure that

the policy did not affect foreign exchange reserves. Thus, as part of the Bank

of Israel monetary policy from 1990 to 1994, the exchange rate constituted a

nominal anchor and was allowed to fluctuate within a diagonal exchange rate

band. In addition, until the end of 1993, the Bank of Israel acted to gradually

reduce the interest rate parallel to the drop in the rate of inflation. This

interest rate policy had two main objectives, which were sometimes

contradictory: The first objective was to maintain the exchange rate within the

boundaries of the band to reduce the vulnerability of the economy to the

irregular behavior of the financial markets resulting from speculative activities

in the foreign exchange market. The other objective was to stimulate real

economic activity to facilitate the absorption of the wave of immigrants that

arrived in the early 1990s.

At the end of

1994, the Bank of Israel raised the interest rate to achieve a more ambitious

inflation target that coincided with the rise in the rate of inflation. This

new monetary policy halted the expansion of the money supply and the effect on

inflation was felt in the following year. The year 1995 was characterized by a

continued increase in the rate of growth; however, from 1996 to 1999 there was

a consistent decline in the growth rate. The period was characterized by a

gradually worsening slowdown, which was evident in the behavior of various

economic indicators, including the unemployment rate, manufacturing output, the

import and export of goods and services, housing starts and number of tourists.

There were also a number of security-related events that raised the level of

uncertainty in the economy, as did the early elections following the

assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, which was accompanied

by slower growth in global trade.

With regard to

structural changes in the economy, the positive effects of the wave of

immigration were still not being fully felt in 1995. On the other hand, some of

the business opportunities that resulted from the progress in the peace process

were being exploited. One of the structural changes that resulted from the

increased access to new overseas markets was the transition to production in

advanced industries at the expense of traditional ones, which began in that

year. The effect of these events was manifested in both positive and negative

economic phenomena. The former included growth in per capita GDP in 1996; an

increase in investment in some industries; the import of long-term capital;

and, in the labor market, a decrease in the rate of unemployment; so much so

that the economy reached a state of almost full employment. On the negative

side, a slowdown was felt in the rate of growth relative to 1994 and 1995. As

in previous years, there was no increase in productivity, which partly

reflected the less-than-full exploitation of human capital, particularly that

of new immigrants, and of the technological improvements that were the result

of investment in previous years. In addition, 1996 saw an increase in the

current account deficit and a substantial increase in the budget deficit in the

wake of the expansion of the public sector and an increase in the number of its

workers, in addition to an increase in their real wages. Up until the middle of

the year, there was an increase in prices due to an expansionary fiscal policy.

In order to limit the negative effects of this fiscal policy on inflation, a

contractionary monetary policy was adopted such that the Central Bank nearly

met its inflation target.

As a background

to the developments in 1997, it is worth mentioning that the period of 1994 to

1996 was characterized by a partial abandonment of fiscal discipline; as a

result of which important structural reforms of the economy were not carried

out and the relative share of the public sector in the economy grew. During

this period, the economy experienced high growth and a decrease in

unemployment; however, at the same time, the deficit in the current account

increased significantly and inflation reached double-digit figures, resulting

in a rapid increase of the government budget deficit and excess demand in the

economy. As a consequence of these developments, one of the main targets

included in the 1997 budget was a decrease in the current account deficit.

The year 1997

saw an end to the boom segment of the business cycle that had characterized

previous years. This was due to a lessening of the impact of the wave of immigration,

a decline in domestic demand and a decrease in investment, with the completion

of the process of adjustment in the capital stock. Despite the decrease that year, the level of

investment was still considered to be high. In contrast to previous years,

fiscal policy in 1997 was contractionary; as a result, demand dropped off,

leading to a decrease in the growth of public consumption and investment. The

raising of tax rates brought about a decrease in disposable income which, in

turn, caused a slowdown in the growth of private consumption.

A contractionary

monetary policy was manifested in a high real rate of interest (about 5%),

which was identical to its level during the second half of 1996. This policy,

which constrained supply and demand in the short term, was adopted in order to

achieve the inflation target (which was indeed achieved) and to maintain the

exchange rate within its band.

In 1997,

structural change in the economy was manifested in the contraction of

traditional industries, such as textiles and clothing. This led to a transfer

of manpower out of these industries, most of which was not absorbed into

knowledge-intensive or service industries. As a result, the level of

unemployment increased, which was accompanied by a slowdown in economic

activity. The contraction of the traditional industries was a result of their

inability to compete under the conditions created by globalization. The reality

in Israel brought about a situation in which production costs were relatively

high, in part due to the increase in the minimum wage and the increase in the

dollar exchange rate relative to European currencies. There were also

security-related events which increased political uncertainty and hampered

trade with the occupied territories and the export of tourist services. An

inevitable result of all this was the deferral of investment. The current

account deficit was reduced during this period to 3.3% of GDP, as compared to

5.2% in 1996. The yield spreads between Israel and overseas led to an increase

in foreign investment and an expansion in credit denominated or linked to

foreign currency. As a result of the widening of the foreign exchange rate

band, there was an increase in exchange rate risk which drastically reduced the

inflow of short-term capital, although the upward trend in foreign investment

continued. Together with the decrease in the current account deficit, this led

to an increase in foreign exchange reserves at the Bank of Israel, which

reached a peak of $20 billion in 1997. This high number was also the result of

large purchases of foreign currency by the Bank of Israel to prevent the

exchange rate from declining below the lower boundary of the band.

The slowdown in

domestic demand and the increase in unemployment continued in 1998, in part due

to the increase in the real interest rate, the slowdown in the growth of global

economic activity and the political and security-related uncertainty. In

contrast, there was an improvement in the current account, which resulted from

the slowdown in domestic demand and the improvement in the terms of trade

(involving a decrease in manufacturing costs, which led to an increase in the

profits of exporters and weakened the effect of the global slowdown on the

economy). Inflation decreased sharply up until August, but from August to

November, there was a sharp increase in prices due to the devaluation of the

shekel, which was a result of the financial crisis that started in Asia, spread

to Russia and from there reached Israel. Up until August of that year, there

was a feeling that inflationary pressures had abated and as a result the

inflation target for 1999 was set at 4% in August and, at the same time, the

Bank of Israel reduced the interest rate by 1.5%. Following a limited

devaluation, the exchange rate settled at a lower plateau; however, the crisis

in Russia, which included an announcement of a moratorium on debt servicing, as

well as the shocks in the financial markets in its wake, reduced flows of

capital to emerging markets. As a result, there was a significant drop-off in

the flow of capital into Israel and a sharp devaluation in the exchange rate

from the end of August until the end of October. There was a major increase in

the inflation rate (and in the expectations of inflation) during this period.

The Bank of Israel raised the interest rate by 4% without direct intervention

in the foreign exchange market, which led to a considerable cooling-off in

expectations of inflation along with a decrease in the price indexes from

December to February.

In 1999, there

was a turnaround in economic activity, particularly during the second quarter.

The acceleration of activity during this period was led by domestic demand and

exports, related to the high-tech bubble. In addition, there was an increase in

employment despite the increase in the rate of unemployment. The recovery

followed three years of economic slowdown and was primarily based on long-term

factors that acted to return the economy to a path of growth, in addition to

transitory factors that acted to accelerate activity during this period.

The slowdown in

economic activity commenced in the last quarter of 2000 and was caused

primarily by domestic and foreign shocks. In Israel, this involved the second intifada in the occupied territories,

which had a direct effect on domestic economic activity; most clearly tourism

and the construction industry. Abroad, this involved a global slowdown –

primarily in the U.S. – which resulted from a global crisis in the hi-tech

industries and the capital markets. These shocks led to a reduction in demand

for domestic products which intensified the recession in Israel.

During the

period 2001–2003, the country experienced its most serious recession since the

establishment of the State of Israel. The period started with sharp decline in the NASDAQ index of hi-tech

shares, which led to a significant reduction in the investment in Israeli

start-up companies and in the hi-tech industry as a whole. A tight monetary

policy also contributed to the lack of growth, which was reflected in a

significant decline in per capita income during 2001 and 2002. The developments

in the U.S. economy, which included a declining rate of growth and a reduction

in investment, led to a contraction in demand for Israeli exports. This period was

also characterized by the opening up of global markets and an intensification

of the globalization process, which were accompanied by a liberalization of the

foreign exchange market.

In 2000,

inflation dropped to zero as a result of the Bank of Israel's tight monetary

policy, which led to high interest rates on loans. The Central Bank urged the

government to continue cutting the budget, thus reducing the deficit and the debt

to GDP ratio, which during the period 2000–2001 reached its lowest level since

the Stabilization Plan in 1985. From 2001 to 2003, there was a further increase

in the rate of unemployment to about 10%, as compared to 6–7% during the

mid-1990s. During the course of 2001, the Bank of Israel continued reducing

interest rates without compromising the achievement of the inflation target

until, at the end of December of that year, it lowered them by 2% - from 5.8%

to 3.8%. This led to a sharp increase in the exchange rate during the first

half of 2002 and a considerable increase in expectations of inflation. The

outcome had been expected: 6.5% inflation, which represented a major deviation

from the inflation target that year. The

trend in prices during 2002 was not uniform: During the first half of the year,

a mix of expansionary economic policies was implemented, which led to the

continued growth of the deficit. This policy mix and the deterioration in the

security situation created a lack of confidence, which increased the demand for

foreign currency. As a result, the shekel was devalued by about 18% from the

beginning of the year until July; a development which threatened Israel's

financial stability. During the second half of the year, the deterioration in

the financial markets was halted by a major change in the policy mix, which was

reflected by the raising of the Bank of Israel interest rate by 4.5% by the end

of June. As part of the policy mix, it was also decided to increase tax rates

and to cut government spending while at the same time raising the deficit

target to 3.9%, even though such steps tend to exacerbate the situation during

a recession. The monetary and fiscal policy mix led to the return of relative

stability in the foreign currency market as well. In 2002, the gradual recovery

in global trade was not yet felt in the hi-tech industries and therefore

despite the real devaluation, which had a greater effect on the exports of

traditional industries, the downward trend in exports continued. The recovery

in the exports of the hi-tech industries began only during the fourth quarter

of 2002.

Following the

recession, which lasted from 2000 until the first half of 2003, a process of

economic growth began and gained momentum from 2004 to 2007. This period was

also characterized by growth in per capita income, a decline in unemployment

rates, the achievement of the government's deficit targets, low inflationary

pressures and a strong banking system. The economy's growth began against the

background of a current account surplus. During this period, interest on the

part of investors in emerging economies increased, which led to greater

activity in the local capital market and a decrease in the Israeli economy's

risk premium. Particularly noticeable was the superior performance of the

Israeli economy in 2006 despite the outbreak of the Second Lebanon War during

the summer of that year.

Budget policy in

2003 was aimed at halting the contraction in economic activity that

characterized the previous two years while the policy in 2004 and 2005 was

aimed at stimulating growth. The policy in 2006 was intended to create the

conditions that would preserve it. The means used to achieve these objectives

included budgetary restraint, a reduction in the tax burden and structural

changes. The main fiscal measures were a

cut in transfer to the public, mainly child allowances, and other measures

aimed at increasing the rate of participation in the labor market.

In view of the

continuing internal and external shocks, the targets set for 2003 were to

maintain financial stability and halt the contraction of the economy. Up until

March of that year, there was uncertainty as to the commitment of the

government to stop the growth in the budget deficit. This fact, combined with

the stalemate in the political-security situation at the beginning of 2003, led

to high real interest rates in the long and short terms; which led to continued

recession, a further decline in per capita income and an increase in the

unemployment rate. Later that year, the real interest rate began declining as a

result of the significant decrease in uncertainty regarding the capability of

the government to meet the deficit target it had set for itself. This decline

began with the publication of the government's economic plan - “The Israel

Recovery Plan,” the approval of U.S. guarantees and the commencement of the

peace process, combined with the rapid end to fighting in Iraq. As a result,

there was a decrease in Israel's risk premium.

The improvement

in the monetary indicators (expected inflation and the nominal and real yield curves)

enabled the Bank of Israel to gradually reduce interest rates up to the end of

the year. The coordinated mix of policies positively effected the expectations

of firms and individuals and led to a sharp increase in stock market prices.

This in turn led to an increase in private consumption during the second half

of 2003. The policy of limiting current government expenditure, as implemented

in 2003, had two opposite effects: On one hand, it created a decrease in

short-term domestic demand (both government and private), which was a result of

the decrease in transfer payments and a drop in real public sector wages and,

on the other hand, it prompted an increase in demand that followed the sharp

rise in stock market prices, which positively affected private consumption. In

2003, there was also a reversal in the trend of both long-term and short-term

capital flows (direct investments), which were partly the result of the

recovery in the hi-tech industries. The result was an appreciation of the

shekel relative to the dollar and, in parallel to the drop in the exchange

rate; the year was characterized by significant decline in prices (-1.9%) which

was well under 1% - the lower boundary of the inflation target.

The years

2003–2007 can be characterized as a period of economic boom and of stability in

the capital market with significant changes in capital market structure

following the reform of the pension funds and the capital market,

whose purpose was reduced concentration and the minimization of a conflict of

interest among financial corporations active in the capital market. With regard

to the public’s asset portfolio, the share of the banks was reduced while there

was an increase in the proportion of tradable assets; particularly domestic

corporate bonds and foreign debt instruments. In the business sector, there was

growth in the share of non-bank financing.

During this

period, there was volatility in the level of prices and the Central Bank

intervened when there was a deviation from the inflation target, which was often

the result of the strengthening of the shekel relative to the dollar. The year

2003 was characterized by a significant drop in the price level, which was a

result of the continuing recession. It was also due to the appreciation of the

shekel against the dollar, which followed the reversal in capital flows –

particularly of short-term capital – as a result of the interest rate spread in

favor of the local economy relative to the developed and emerging economies.

In order to

raise inflation to within the target range of 1-3%, the Central Bank

implemented an expansionary monetary policy, which was manifested in a gradual

reduction in the interest rate. However, the policy did not succeed in

minimizing the deviation from the inflation target and, as mentioned, 2003 was

characterized by disinflation at a rate of -1.9%. As opposed to its previous

behavior, the Bank of Israel maintained a relatively low interest rate during

the period of 2004–2007, while also keeping a low level of inflation that was

within the target or even lower. The stable level of prices that was

maintained for most of the period was also the result of a fiscal policy that

supported a reduction in government spending and the financial stability that

resulted from, among other things, the stable security situation in Israel and

global economic growth. The economy’s risk premium, as measured by the spread

between the yield on 10-year Israeli government bonds and comparable yields in

the U.S., declined, which made it possible to maintain relatively low interest

rates.

In 2007, a

global financial crisis (the sub-prime crisis) began spreading from the United

States to the rest of the world and later affected the global economy.

Initially, the crisis was characterized by the collapse of financial

institutions in the U.S. In the subsequent stage, the activity of the markets

was severely affected and there was a sharp decline in the prices of financial

assets. It also led to liquidity and credit shortage and a crisis of confidence

in the financial system. The global economy experienced a major slowdown, which

began in the U.S. and then spread to other developed economies, particularly in

Europe, and later on to Asia and the emerging economies. The crisis led various

nations to enact large and often coordinated cuts in interest rates and

large-scale programs for fiscal intervention, which grew in size over time. In

general, policy responses initially focused on shoring up the financial system

and relieving the liquidity shortage. Subsequently, focus shifted to

stimulating aggregate demand. These responses are important for understanding

the background for the actions of policy makers in Israel in 2008.

In 2008,

following five years of rapid growth, the Israeli economy began sliding into a

recession, as the global crisis worsened. During the year, the upward trends

that characterized the period of rapid growth were still apparent; however, the

effects of the global crisis, including significant increases in the global

prices of crude oil and raw materials, were increasingly felt toward the end of

2008. . The growth rate in 2008 stood at 4%, with demand factors leading the

growth. The demand pressure was manifested in a rise in inflation, an

appreciation of the real exchange rate and a decrease in the current account

surplus. In addition, the unemployment rate declined, nominal wages increased

and employment of low-skilled workers expanded. The effect of the crisis in the

latter part of the year included a sharp decline in exports and tax revenues as

well as a slowdown in the growth rate of private consumption. The downturn

during the course of the year could also be seen in the trend of inflation.

Until September, inflation remained high as a result of the rise in the global

prices of oil and other raw materials and the economy’s surplus demand; while

the period subsequent to September saw a steep decline in inflation as a result

of the decrease in global prices and the curbing of excess demand.

For 2008 as a

whole, inflation was 3.8%, which exceeded the upper boundary of the target of

3%. The financial system was also subject to major shocks, although the effect

of the global crisis was felt less than in other economies. The intensity of

the shocks can be seen in, among other things, a substantial decrease in the

prices of shares and corporate bonds and the increase in premiums in the credit

market. The shock to the financial system and the increase in risk led to a

contraction in the supply of credit and a sharp rise in the costs of raising

capital. Monetary policy was largely a response to global developments – the

rise in the prices of oil and commodities and the worsening assessments of the

severity of the crisis and its effect on Israel.

The

implementation of monetary policy was not uniform throughout the year. In March

and April the interest rate was lowered; from then until September it was

raised; and from September until the end of the year it was lowered

drastically, reaching its lowest level ever. Simultaneous with the Bank of

Israel’s lowering of the interest rate, the increase in risk created the

opposite pressure on banks’ lending rates. The Bank of Israel adopted another

policy that was not normally used, which involved the purchase of foreign

currency in large quantities during the course of the year in order to increase

reserves, in response to the accelerated appreciation of the exchange rate.

Fiscal policy in 2008 was expansionary, for the first time since 2004,

primarily in the form of further reductions in direct tax rates. The combination

of this policy with the slowdown in economic activity that lowered tax revenues

led to a rise in the deficit. The global crisis had a more moderate effect on

Israel relative to other economies. This is explained primarily by the

increased resilience of the Israeli economy as a result of the improved

implementation of fiscal policy, which involved a controlled rate of growth in

expenditure as an anchor for policy, thus making it possible to reduce the

deficit and the public debt.

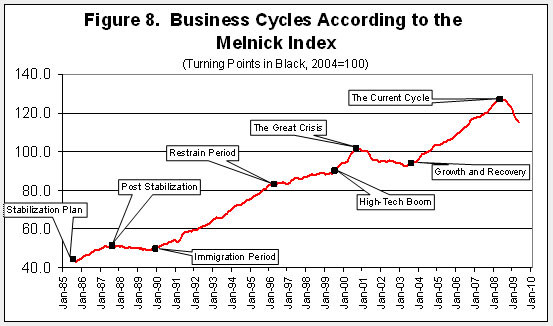

The Business Cycle from the Stabilization Plan Until 2008

The business

cycle from the Stabilization Plan until the present time can be summarized as

periods of growth, slowdown and recession in accordance with the changes in the

Melnick Index.

The first period

– the period of the "Stabilization Plan" (growth) – began in November

1985 and ended in August 1987. Following stabilization, there was a substantial

increase in private consumption and total productivity, as well as a

significant increase in GDP in the short term.

Table 2: Business Cycles

in Israel 1986-2008

Cycle

|

Cycle Type1

|

Start

|

Conclusion

|

Melnick Index 2

|

Stabilization Plan

|

Growth (22) |

November 1985 |

August 1987 |

9.3 |

Post-stabilization

|

Recession (27) |

September 1987 |

December 1989 |

-1.3 |

Immigration period

|

Growth (112) |

January 1990 |

June

1996 |

8.2 |

Period of restraint

|

Slowdown (36) |

July

1996 |

July

1999 |

2.2 |

The hi-tech boom

|

Growth (14) |

August 1999 |

October 2000 |

9.6 |

The great crisis

|

Recession (34) |

November 2000 |

August 2003 |

-2.7 |

Growth and recovery

|

Growth (56) |

September 2003 |

May

2008 |

6.4 |

The current cycle3

|

Recession |

June

2008 |

|

-8.2 |

1 Duration in number of

months appears in parenthesis.

|

2 Annual rate of change

in percent.

|

3 Until April 2009

|

This was

followed by a period of “post-stabilization” (recession) which began in

September 1987 and ended in December 1989 with the beginning of the mass wave

of immigration. This period was characterized by a restructuring of the

economy, which involved the elimination of structural distortions created

during the period of high inflation.

This was

followed by the “Immigration Period” (growth) which commenced in January 1990

and ended in April 1996. During this part of the cycle, the economy benefited

from the fruits of the Stabilization Plan, in parallel to the implementation of

a wide range of economic reforms.

The “Period of

restraint” (slowdown) began in May 1996 and ended in July 1999. This slowdown

began about 18 months after the adoption of a very tight monetary policy at the

beginning of 1995 with the objective of reducing inflation. This policy had a

significant impact as the effects of the mass wave of immigration began to

peter out and the construction industry began to contract. At the beginning of

1997, a restrictive fiscal policy was adopted, which, together with the

monetary restraint and the waning effect of the mass wave of immigration, had a

prolonged moderating effect on economic activity, which lasted for a period of

three years.

The “Hi-tech

boom” (growth) began in August 1999 and ended abruptly in September 2000. This

stage of the cycle was characterized by an endogenous transition from slowdown

to growth, but its conclusion was the result of external shocks: the crash of

the NASDAQ and the beginning of the intifada. This cycle was characterized by

non-uniform growth which was led by the hi-tech industries, whose output is

mainly destined for export.

The next stage

of the cycle, the “Great crisis” (recession), which began in October 2000 and

ended in August 2003, was characterized by an unprecedented recession that

resulted in a decrease in real GDP. This stage was a result of external shocks,

as described above.

The subsequent

“Growth and recovery” stage (growth) from September 2003 to May 2008 was

characterized by a rapid increase in per capita income, a decrease in

unemployment, the achievement of deficit targets by the government, low

inflationary pressure and a robust banking system. This can be viewed against

the background of an improvement in the management of government policy, a

loosening of monetary restraint on the part of the Bank of Israel and an

increase in global trade.

And finally, the

“Global crisis” (recession) has lasted from June 2008 until the present time.

This stage of the business cycle can be explained by the global financial crisis,

which began in the United States and then spread to the entire world.