The Bedouin

by Dr. Yosef Ben-David

(Updated 2016)

Israel’s Bedouin citizens – a minority within the

Arab minority – have in recent years received increased attention, both

from the media and from government institutions.

The process of integrating the Bedouin into Israeli

society takes place on two levels – the formal or by government

policy; and the informal, by changing relationships with Israeli

society in general and Jewish society in particular.

The process, as may be expected, is fraught with

"natural" difficulties experienced by this cultural group:

- the transition from a traditional, conservative

society which only two generations ago was nomadic, entails relinquishing

values, customs and a traditional economy;

- the Bedouin have to cope with the process of

urbanization – the very antithesis of their nomadic tradition –

and the attending poverty and crime rate;

- the Bedouin to some extent fail to distinguish

between objective difficulties and those connected with their changing

sub-culture and thus feel an exaggerated sense of deprivation.

Yet a comparison of the situation of the Bedouin in

Israel to that in Arab countries will show that Israeli Bedouin enjoy

conditions that their brethren lack, mainly in two areas: welfare and land

ownership.

Israel’s attitude towards its Bedouin citizens has

generally always been positive. Well aware of the difficulties of the Bedouin and

based on a thorough knowledge of the subject, recent governments

have begun taking steps to solve the problems with unprecedented

determination and allocation of the necessary funds.

In January 2013, the Israeli government created a policy designed to solve a range of problems affecting Israel's Bedouin population. This January 2013 plan, named after then-minister Ze'ev Binyamin Begin, was created to enhance and expand technological and adult education, develop industrial centers, establish employment guidance centers, assist in bolstering Bedouin local governments, and improve transportation systems, centers of excellence for students and support for Bedouin women who want to work or even begin their own businesses.

The first Bedouin high-tech company in Israel, Sadel Technologies, was cofounded by Ibrahim Sana, a Bedouion, and his two Arab-Israeli business partners. Sadeltech provides their clients with services including but not limited to: mobile app development, web application development and software quality assurance. Most of the employees at Sadeltech are Bedouins who have graduated from computer science programs at Israeli universities and have a tough time finding work; their first Jewish employee was hired in early 2016.

- Demography

- Education

- Health Services

- IDF Service

- Bedouin in the Negev

- Bedouin in Central Israel

- Bedouin in Northern Israel

- Conclusion

Demography

The Bedouin population in Israel currently numbers

210,000 persons who live in all regions of the State, most notably in the Negev.

The Bedouin population has increased tenfold since the

establishment of the State (1948), due to a high natural increase –

about 5% – which is unparalleled in Israel, or elsewhere in the Middle

East. A high fertility rate related to traditional social values regarding

size of family and/or tribe as a political advantage, as well as modern

health and medical services with easy access, which reduced infant

mortality and increased life expectancy, are responsible for this figure.

Education

More than anything else, education can contribute to

the integration of the Bedouin into Israeli society. Under the Compulsory

Education Law, every Bedouin child is entitled to twelve years of free

education and the law is very strictly enforced, at least at the

elementary school level. Three factors enhanced implementation: an

awareness of the necessity and the benefits of an education as an economic

and social-mobility tool; the idleness of children and youngsters in the

wake of moving to permanent settlements (they had been the main labor

force tending the fields and the livestock); and the establishment of a

relatively large number of schools in the scattered locations of the

Bedouin.

Within a single generation, the Bedouin of Israel have

succeeded in reducing illiteracy from 95% to 25%; those still illiterate

are aged 55 and above.

Thirty to fifty percent of the students in elementary

schools (depending on location) go on to high school, a ratio similar to

that elsewhere in the country’s Arab sector. They attend Bedouin high

schools in the Negev and Arab high schools in the central and northern

regions of the country.

Some 650 Bedouin – 30% of the Bedouin high school

graduates of 1998 – were enrolled as of 2002 in post-secondary education.

About 60 percent of them attended teacher training colleges and 40 percent

studied at the universities (including the Technological College of Be’er

Sheva). In addition, 35 students enrolled in universities abroad,

since they did not qualify for admission to Israeli institutions; the

universities now tend to ease admission standards for Bedouin students.

Health Services

The National Health Insurance Law (NHIL) which took

effect on January 1, 1996 considerably improved health services for about 30% of the

Bedouin population who had not belonged to a sick fund. According to the

NHIL, every resident is entitled to a basket of health services provided

by clinics, specialists and hospitals.

Mother-and-child care centers provide health education,

check-ups monitoring development and immunization. Today, hardly any

Bedouin women give birth at home; going to hospital makes the mother

eligible for a grant from the National Insurance Institute and provides

unaccustomed pampering.

Israel Defense Forces Service

Since 1948, Bedouins have served in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in large numbers, mostly in scouting or tracking units. A Bedouin scouting unit was established in 1970 in the IDF's Southern Command, and similar units are now in other regions. In 1986 a desert-scouting unit was formed and has been stationed near the Gaza Strip more recently. There is a monument honoring Bedouin soldiers' contribution to Israel and its army in the Galilee. In 2003, the IDF formed several specialized "search & rescue" units to serve the residents of the Arab, Bedouin and Druze communities in Israel. Despite their integration into the IDF, Israel's Bedouin population remains largely unintegrated into the rest of Israeli society, something the Begin Plan aims to change.

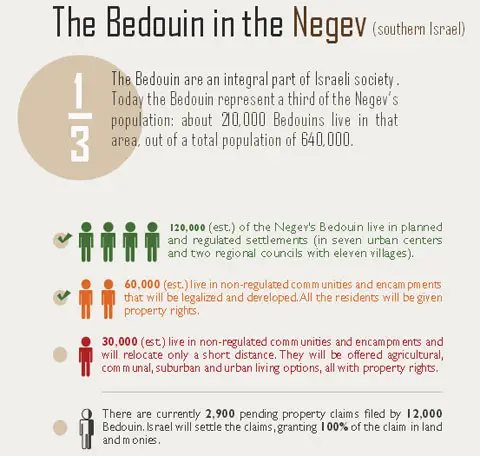

The Bedouin in the Negev

Ninety percent of the Bedouin tribes in the Negev hail from the

Hejaz, a region in the north of the Arabian peninsula. Ninety percent of the Negev's Bedouin population is located in the area between the cities of Beer Sheva, Arad, Dimona and Rahat.

Education: There are about 33 elementary

schools, three high schools and three vocational schools for the Bedouin

community in the Negev. At the elementary level, with an enrollment of

95%, the school population is made up of equal proportions of boys and

girls. But because Bedouin society regards females as inferior and does

not encourage them to study, girls make up no more than 10% of the pupils

in high schools. At first many teachers had to be brought in from outside

the community, today 60 percent of the teaching staff is Bedouin.

All the Bedouin high schools and 60% of the elementary

schools in the Negev, are located in the seven Bedouin towns there. Over

the past five years, extensive resources have been invested in schools,

especially in buildings, services, water pipes, heating and more.

Computers and laboratories have also been introduced.

Health: There are clinics in all seven Bedouin

towns in the Negev (in Rahat, proclaimed a city in 1994, there are four

clinics and a day-hospital). The medical staff includes Jews and Arabs;

fifteen of them are Bedouin doctors. Most of the Bedouin living outside

the towns can reach the clinics easily; in the more outlying areas,

several mobile clinics provide services in the mornings.

A total of 12 clinics provide services in the Negev at

present (one clinic per 6000 persons); another 10 clinics are in various

stages of establishment. Hospital facilities are available in Be’er

Sheva. If a gap still exists between health services in the rest of the

country and in the Bedouin towns, it relates more to the physical domain

than to the level of medicine.

Land Rights: In most countries in the Middle East the Bedouin have no land rights, only users’ privileges. Israeli Law is

derived largely from Mandatory (British) law which in turn incorporated

much Ottoman law. Under Israeli law, a person who has not registered

his/her land in the Land Registry cannot claim ownership; but in the mid

1970s Israel let the Negev Bedouin register their land claims and issued

certificates as to the size of the tracts claimed. These certificates

served as the basis for the "right of possession" later granted

by the government. Following the signing of the Treaty of Peace with

Egypt, it became necessary to move an airport to a locality inhabited by

5000 Bedouin. The government, recognizing these land claim certificates,

negotiated with the certificate holders and paid compensation to them.

Most moved to Bedouin townships, built houses and established businesses.

In recent years the Ministerial Committee for the

Advancement of Bedouin Affairs has undertaken to solve the problem of land

ownership and has been assured of the necessary funds. The government is

willing to leave some 20% of the land claimed in Bedouin possession and to

compensate them for the remainder. In the past, tensions relating to land

ownership have led to violence. A solution is now possible, but it

requires the willingness and goodwill of both partners.

Two kinds of land offenses make media headlines:

illegal building and grazing in protected areas:

Illegal building: Tents and light structures

(shacks and huts) built illegally are treated forgivingly. But

construction of houses of stone or concrete without a building permit is

considered an offense, since adequate infrastructure and services cannot

be provided. Some 2,000 such locations with buildings already exist,

scattered over an area of about 1,000 square kilometers.

Grazing in protected areas: Most of the livestock

of the Bedouin in the Negev who keep flocks of sheep and goats are

registered and approved by the Ministry of Agriculture, which provides

pasture land outside the Negev for six to seven months of the year, since

the carrying capacity of the Negev is limited. Owners who, for reasons of

tax evasion, have not registered their livestock and do not receive

Ministry of Agriculture services, frequently trespass on nature reserves

or populated areas. They are liable to be punished under the law.

Permanent locations: The establishment of

permanent towns did not begin until the Bedouin themselves constructed

buildings to replace tents. But the urbanization process is by no means

simple, as the planners have to deal with issues involving tradition and

social structure and the Bedouin themselves have difficulty in

articulating their wishes in planning terms.

The first Bedouin town, Tel Sheva, was founded in 1967.

Here all possible mistakes were made, both by the planners and by

government officials. Since then another six towns have been established

in the Negev and an effort was made to learn from each previous

experience. But the planning concept focused on urban settlement, while

many Bedouin wanted to live in rural localities. Today there are plans to

found such rural localities and it is hoped that they will satisfy the

traditional aspirations of the Bedouin.

The Bedouin urban population in the Negev (1998) |

| Rahat |

28,000 |

| Tel Sheva |

7,000 |

| Aro’er |

6,200 |

| Keseifa |

5,500 |

| Segev Shalom |

2,600 |

| Hura |

2,400 |

| Lakiya |

1,500 |

| Total |

53,200 |

The total Bedouin population of the Negev is over

110,000, which means that about 57,000 are still scattered in outlying

areas. It will be Israel’s task in the near future, to solve, together

with the Bedouin, the problems of their settlement in towns and rural

communities.

Livelihood: The desire of about 30% of the Bedouin in

the Negev to retain traditional occupations – the raising of livestock and

dry farming – as a source of primary or additional income, causes them to

seek pasture land, the supply of which is decreasing due to development and

increased quantities of livestock. Given the arid conditions of the Negev,

the government, though increasing quotas from time to time, providing

veterinary services and refraining from the importation of mutton, must

limit pasture land. This is at times depicted in the media as cruel, and the

Bedouin as victims of high-handedness.

Other sources of livelihood are:

1. Thirty percent of the Bedouin in the Negev have

permanent jobs (in factories, government services etc.).

2. A similar percentage of unskilled workers cannot

obtain permanent jobs and they are the immediate victims when recession and

unemployment strike. The National Insurance Law guarantees minimal income to

the unemployed, the elderly, the disabled or ill and to orphans and widows.

3. In private enterprise: they have succeeded to capture

three niches in which neither Jews nor Arabs compete (providing income to an

estimated 25% of the population): as agricultural contractors with modern

mechanical equipment; as owners of trucks, utility vehicles, buses and cabs,

or as salaried employees of transportation companies; and as contractors for

development work, involving the use of heavy mechanical equipment.

The Bedouin in Central Israel

No Bedouin lived in central Israel in 1948. The fact that

10,000 currently live in this region is the result of migration from the

Negev, due to two main factors:

Pasture migration: In 1957 the Negev was struck by

drought which lasted for six years. The military administration, responsible

for the Negev Bedouin localities at the time, came to the aid of the owners

of large herds who requested permission to move to State-owned pasture land

in central Israel. This migration led to the establishment of dozens of

Bedouin settlements from Kiryat Gat to Mount Carmel, which developed

pleasant social and political relations with their Jewish neighbors. In 1977

the government decided that the Bedouin should return to the Negev. Those

who had land in the Negev returned there, but the majority remained in

Central Israel, because they had abundant pasture land and some of the

family members had found jobs, especially in and around the major Jewish

cities. In 1992 a new policy, under which they were offered additional rural

localities, was adopted; but the process of settlement will undoubtedly last

many years.

Labor migration: The second factor that led to the

migration of Bedouin to central Israel was the search for work, especially

by families that lacked land and livestock. This migration process, which

lasted from 1954 to 1970, created Bedouin centers in the cities of Ramle and

Lod and the villages of Taibe and Kafr Kassem; lesser numbers settled in

other Arab villages. The migrants belonged to two socio-economic groups:

those who had left behind land in the Negev and those (the majority) who had

not. The latter obtained permanent jobs and income and had no intention of

leaving. Most of those who had left land in the Negev returned there in

1980, when the government recognized land claim certificates (see above -

Land rights).

In the cities: The Bedouin who moved to

Central Israel adapted quickly to urban life, free as they were of the

social and political pressure of the Negev Bedouin who opposed moving to the

townships set up for them by the government. They moved into houses

abandoned by Arabs who had fled the country during the War of Independence,

or built shacks (such as the train-station section of Lod). The government

is now planning housing projects, taking their traditional needs into

consideration. Having become permanent residents and enjoying better

national and municipal services, the Bedouin show much interest in both

general and municipal politics. in these cities they have also developed

special relations with the two dominant communities, the Arabs and new

Jewish immigrants.

In the villages: Paradoxically, the Bedouin

who migrated from the Negev to Arab villages were not able to create

positive relations with the villagers, despite a common religion and

language; they are, instead, considered foreign implants. In 1997 the Kafr

Kassem Local Council published a leaflet criticizing their Bedouin

neighbors, even demanding their eviction. The incompatibility between the

Bedouin, who bought small plots of land for agriculture, and the villagers

seems to be linked to the cultural-historical difference between farmers and

desert dwellers. But like all Israeli citizens they enjoy education, health

and welfare services, despite their claims of being discriminated against by

the local authorities, especially in the separate neighborhoods that they

have built for themselves in each village.

The Bedouin in Northern Israel

The Bedouin in Galilee and the Jezreel valley, numbering

about 50,000, unlike those in the Negev and in the Central region, hail from

the Syrian desert. At the beginning of the century their nomadic way of life

and militancy put them in a position to harass villages and demand tribute,

giving them a sense of superiority over the fellahin (farmers). During the

British Mandate the Galilee Bedouin were encouraged to purchase small plots

of land and such purchases were recorded in the Land Registry as legal

possession.

Towards the end of the British Mandate and during the

struggle for the establishment of the State of Israel, many Bedouin joined

the Jewish forces, believing that the Jewish state would be generous to

them. This also explains the continued good relations after the

establishment of the State, as manifested, first and foremost, in

volunteering for the security forces and serving on the front lines;

volunteering is considered by the Bedouin to be part of their blood-pact

with the State of Israel.

One example of the good relations between the State and

the Bedouin in the North is the tolerance displayed by the government

regarding violations of building laws, non-expropriation of land and the

establishment of the townships of Beit Zarzir and Ka’abiya.

Conclusion

Whereas the Negev Bedouin are ambivalent in their

attitude toward the State of Israel and their identification with it, the northern

Bedouin identify with it almost fully. This is manifested, first and

foremost, in the extent of volunteering for the security services. As a

result, the Bedouin in the North are rewarded with a friendly attitude, both

from the establishment and from Jewish society at large.

Sources: Israeli

Foreign Ministry, Embassy of Israel. Dr. Ben-David is an associate researcher at the

Jerusalem Institute of Israel Studies.

|