Born in Ulm, Germany, Einstein grew up in Munich. As a boy, he already showed great interest in and

talent for mathematics and physics. His family moved to Italy,

and young Albert, unhappy with the authoritarian discipline of the German

schools, went on to study at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology

in Zurich. Of the four graduates in 1900, he was the only one who was

not given a position at the Institute; instead, he became a Swiss citizen

and took a job at the Swiss patent office in Berne.

In 1905, Einstein was granted

a doctorate by the University of Zurich.

His thesis, Eine neue Bestimmung der Molekuldimensionen (A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions),

Berne, 1905, was his first independently

published work (five papers had previously

been published in Annalen der Physik). The

Library's copy of Einstein's twenty-one-page

doctoral dissertation was received on January

18, 1907, as a “Smithsonian Deposit.” In "Subtle

is the Lord . . . ” The Science and Life

of Albert Einstein (New York, 1982),

Abraham Pais, of Rockefeller University,

writes:

It is not sufficiently realized that Einstein's thesis is one of

his most fundamental papers ... It had more widespread application

than any other paper Einstein ever wrote. of the eleven scientific

articles published by any author before 1912, and cited most frequently

between 1961 and 1975, four are by Einstein. Among these four, the

thesis ... ranks first.

In 1921, Einstein accompanied Chaim

Weizmann on a tour of the United States to raise funds for the proposed

Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Among other honors, Einstein was received

at the White House by President Harding, The Library has a photograph

taken at the Farewell Dinner of the American Palestine Campaign. On

it are Professor and Mrs. Einstein, financier Felix Warburg, Zionist

leaders Robert Szold, Morris Rothenberg, and Rabbi

Stephen S. Wise, as well as Jefferson Seligman of the banking family.

The Prints and Photographs Division also contains a print of a pen and

ink drawing of Einstein by Robert Kastor on which is inscribed in Einsteins

own hand in German:

Nature has so wonderful a harmony that at times, one can draw conclusions

from distant facts about not yet observed phenomena, and do so with

such certainty, that he can look forward without fear to comparing

these conclusions with observed reality.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Einstein resigned his position in the Royal Prussian

Academy of Sciences. On October 17 of that year the Einsteins arrived

in the United States and settled in Princeton, where Einstein had accepted

a professorship at the Institute for Advanced Studies. Five years later,

July 13, 1938, he wrote to Dr. Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress:

My good friend, Professor E. Lowe, informs me that you would like

to have one of my manuscripts for the Library of Congress. I am sending

you herewith a specially prepared copy of my newest theory which I

consider particularly worthy.

Einstein, a Jew fleeing Nazi terror, finding refuge

in the United States, expresses his gratitude to this haven which became

his home through a gift to the Library of Congress. The enclosed manuscript

was “Einheitliche Feldtheorie” (Unified Field Theory), inscribed

and dated in Einstein's hand 6 VII (July 6), 1938. Einstein began his

pursuit of a unified field theory in 1919 and continued it to the last

years of his life.

Five years later, in 1943, his new country now at war

with the one he fled, Einstein aided the War Bond campaign by presenting

through it another manuscript to the Library of Congress. (A Kansas

City life insurance company was awarded the honor of being the official

donor for its $6.5 million purchase of bonds.) He described his manuscript

in an accompanying note:

The following pages are a copy of my first paper concerning the theory

of relativity. I made this copy in November 1943. The original manuscript

no longer exists having been discarded by me after its publication.

The publication bore the title Zur Electrodynamic Bewegter Körper.

A. Einstein, 21 XI, 1943

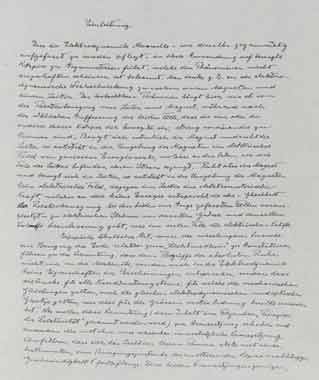

Displayed at left is the

first page of a holograph copy of “Zur

Elektrodynamik bewegter Korper,” which

Einstein described as his first paper concerning

the theory of relativity. He had discarded

the original manuscript after it had been

published in Annalen

der Physic in

1905. In November 1943, Einstein rewrote

this paper so that it might be presented

to the Library of Congress to help promote

the sale of U.S. War Bonds (Albert Einstein. “Zur

Elektrodynamik bewegter Korper,” November

1943, Manuscript Division).

The Library proudly

exhibits its new treasure, noting that

it was first published in the Annalen der

Physic, Leipzig, 1905, and that it was:

Written by Einstein at the age of twenty-six, while

he was living at Berne, Switzerland, the theory, though not immediately

recognized as such, represents the first step toward one of the greatest

intellectual triumphs of modern times.

In March 1955, a month before he died, Einstein wrote

to Kurt Blumenfeld, “I thank you belatedly for having made me conscious

of my Jewish soul.” This consciousness had come forty-five years

earlier when Blumenfeld directed him to Zionism.

Although never a member of a Zionist organization, in 1924 Einstein

did become a member of a Berlin synagogue to declare his Jewish identity

and he served the cause of Zionism throughout his adult life. He visited

Palestine, served on the Board of the Hebrew University, and willed

his papers to it. In 1946, Einstein appeared before the Anglo-American

Committee of inquiry on Palestine and made a strong plea for a Jewish

homeland.

Al Aumuller.

America Gains a Famous Citizen (Albert Einstein),

October 1, 1940.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

Prints and Photographs

Division

When Israel's first president, Chaim

Weizmann, died, Israeli Prime Minister David

Ben Gurion invited Einstein to stand as a candidate for the office,

but Einstein declined because, he said, though he was deeply touched

by the offer, he was not suited for the position. During his final illness,

Einstein took with him to the hospital the draft of a statement he was

preparing for a television appearance celebrating the State of Israel's

seventh anniversary, but he did not live either to complete or deliver

it.

Sources:Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress,

1991). Portrait photo: Robert Kastor. January

21, 1922,

Pen and ink on paper. Prints and Photographs

Division, Library

of Congress