The Greeks & the Jews

(332 - 63 BCE)

In the Table of Nations in Genesis 10.1-32, which lists

the descendants of Noah and the nations they founded, the Greeks

appear under the name "Yavan," who is a son of Yaphet.

Yavan is parallel with the Greek word, "Ionia," the Greek

region of Asia Minor; "Yaphet" is parallel with the Greek

word, "Iapetus," who is the mythological father of

Prometheus in Greek legend. Two other Greek nations appear in the

table: Rhodes (Rodanim) and Cyprus (Kittim and Elishah). The sons of

Shem, brother to Yaphet, are the Semitic (named after Shem) nations,

including the Hebrews. Imagine, if you will, the Hebrew vision of

history. At some point, in the dim recesses of time, after the world

had been destroyed by flood, the nations of the earth were all

contained in the three sons of Noah. Their sons and grandsons all

knew one another, spoke the same language, ate the same mails,

worshipped the same god. How odd and unmeasurably strange it must

have been, then, when after an infinite multitude of generations and

millennia of separation, the descendants of Yavan moved among the

descendants of Shem!

|

They came unexpectedly. After two centuries of

serving as a vassal state to Persia, Judah suddenly found itself the

vassal state of Macedonia, a Greek state. Alexander

the Great had conquered Persia and had, in doing so, conquered

most of the world. For most of the world belonged to Persia; in a

blink of an eye, it now fell to the Greeks.

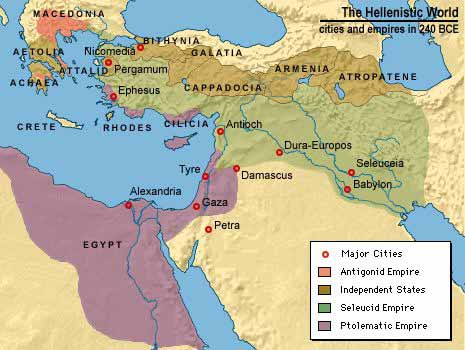

This great Greek empire would last no longer than

Alexander's brief life; after his death, altercations between his

generals led to the division of his empire among three generals. One

general, Antigonus and then later Ptolemy, inherited Egypt; another,

Seleucus, inherited the Middle East and Mesopotamia. After two

centuries of peace under the Persians, the Hebrew state found itself

once more caught in the middle of power struggles between two great

empires: the Seleucid state with its capital in Syria to the north

and the Ptolemaic state, with its capital in Egypt to the south. Once

more, Judah would be conquered first by one, and then by the other,

as it shifted from being a Seleucid vassal state to a Ptolemaic

vassal state. Between 319 and 302 BCE, Jerusalem changed hands seven times.

Like all others in the region, the Jews bitterly

resented the Greeks. They were more foreign than any group they had

ever seen. In a state founded on maintaining the purity of the Hebrew

religion, the gods of the Greeks seemed wildly offensive. In a

society rigidly opposed to the exposure of the body, the Greek

practice of wrestling in the nude and deliberately dressing light

must have been appalling! In a religion that specifically singles out

homosexuality as a crime against Yahweh, the Greek attitude and even

preference for homosexuality must have been incomprehensible.

In general, though, the Greeks left the Jews

alone; adopting Cyrus's policy, they allowed the Jews to run their

own country, declared that the law of Judah was the Torah,

and attempted to preserve Jewish religion. When the Seleucid king,

Antiochus IV, desecrated the Temple in 168 BCE, he touched off a Jewish revolt under the Maccabees;

for a brief time, Judah became an independent state again.

During this period, Jewish history takes place in

several areas: in Judah, in Mesopotamia and other parts of the Middle

East, and Egypt. For the dispersion of the Jews had begun during the

Exile, and large, powerful groups of Jews lived all throughout the

Persian empire and later the Hellenistic kingdoms

("Hellenistic"="Greek"). The Greeks brought with

them a brand new concept: the "polis," or

"city-state." Among the revolutionary ideas of the polis was the idea of naturalization . In the ancient world, it

was not possible to become a citizen of a state if you weren't born

in that state. If you were born in Israel, and you moved to Tyre, or

Babylon, or Egypt, you were always an Israelite. Your legal status in

the country you're living in would be "foreigner" or

"sojourner." The Greeks, however, would allow foreigners to

become citizens in the polis ; it became possible all

throughout the Middle East for Hebrews and others to become citizens

of states other than Judah. This is vital for understanding the

Jewish dispersion; for the rights of citizenship (or

near-citizenship, called polituemata ), allowed Jews to remain

outside of Judaea and still thrive. In many foreign cities throughout

the Hellenistic world, the Jews formed unified and solid communities;

Jewish women enjoyed more rights and autonomy in these communities

rather than at home.

|

The most important event of the Hellenistic

period, though, is the translation of the Torah into Greek in Ptolemaic Egypt. The Greeks, in fact, were somewhat

interested (not much) in the Jewish religion, but it seems that they

wanted a copy of the Jewish scriptures for the library at Alexandria.

During the Exile, the Exiles began to purify

their religion and practices and turned to the Mosaic books as their

model. After the Exile, the Torah became the authoritative code of the Jews, recognized first by Persia

and later by the Greeks as the Hebrew "law." In 458 BCE,

Artaxerxes I of Persia made the Torah the "law of the Judaean king."

So the Greeks wanted a copy and set about

translating it. Called the Septuagint after the number of

translators it required ("septuaginta" is Greek for

"seventy"), the text is far from perfect. The Hebrew Torah had not settled down into a definitive version, and a number of

mistranslations creep in for reasons ranging from political

expediency to confusion. For instance, the Hebrew Torah is ruthlessly anti-Egyptian; after all, the founding event of the

Hebrew people was the oppression of the Hebrews by the Egyptians and

the delivery from Egypt. The Septuagint translators—who are, after

all, working for the Greek rulers of Egypt—go about effacing much

of the anti-Egyptian aspects. On the other hand, there are words they

can't translate into Greek, such as "berit,"

which they translate "diatheke," or "promise" (in

Latin and English, the word is incorrectly translated

"covenant").

Despite these imperfections, the Septuagint is a

watershed in Jewish history. More than any other event in Jewish

history, this translation would make the Hebrew religion into a world

religion. It would otherwise have faded from memory like the infinity

of Semitic religions that have been lost to us. This Greek version

made the Hebrew scriptures available to the Mediterranean world and

to early Christians who were otherwise fain to regard Christianity as

a religion unrelated to Judaism. Even with a Greek translation, the

Hebrew scriptures came within a hair's breadth of being tossed out of

the Christian canon. From this Greek translation, the Hebrew view of

God, of history, of law, and of the human condition, in all its

magnificence would spread around the world. The dispersion, or

Diaspora, of the Jews would involve ideas as well as people.

Sources: The

Hebrews: A Learning Module from Washington State University,

�Richard Hooker, reprinted by permission. Maps courtesy of Prof.

Eliezer Segal's site.

|