An Illuminated Megillah

The Jewish attitude to visual art is well described by

art historian Bezalel Narkiss in his introduction to Hebrew illuminated

Manuscripts, Jerusalem, 1969:

It is generally assumed that Jews have an aversion to

figurative art. This assumption is, in a way, true, since Jewish life in

accordance with the halakah, has been directed toward belief and righteous

behavior, with a verbal rather than visual expression of its tenets.

However, artistic expression, far from being prohibited,

was actually encouraged, either for educational purposes or for what is

known as hiddur mitzvah, that is, adornment of the implements

involved in performing rituals. Once these reasons were established, a

place for artistic expression was found in Judaism. Gradually, the art

gathered momentum. Embellishing biblical, ritual, legal, or even Hebrew

secular books and manuscripts was one of the most important ways in which a

Jew could express his devotion to the written word.

The special adornment of objects employed in ritual

observance is most pronounced in the illustration and illumination of the Purim megillah, the Passover Haggadah, and the marriage ketubah. From the Hebraic

Section of the Library, we draw notable examples of these as well as a most

interesting illuminated Shivviti tablet, and a representation of the

most Jewish of art forms, micrography.The most joyous of Jewish holidays is the Festival of

Purim. It is a day for merriment-eating and drinking, "until one can

no longer discern between blessed Mordecai and accursed Haman"--a day

of exchanging gifts and giving charity to the poor. It commemorates the

events in ancient Persia described in the Biblical Book of Esther: The

great monarch King Ahasuerus, whose kingdom extends from "India unto

Ethiopia," in a moment of rage, deposes his queen Vashti, then sets

about choosing another in her stead, the queenly post being won by the fair

young maiden Esther, who, unbeknown to the king, is a Jew. Ahasuerus then

raises a certain Haman to be his chief minister. Mordecai, cousin of the

new queen, refuses to bow to the imperious Haman, who determines to punish

not only Mordecai but his whole people with him. Through the intercession

of Queen Esther-as well as the fortuitous saving of the king's life by

Mordecai-Haman's wicked plan, the destruction of all the Jews in the realm,

is thwarted, and turned against him. By royal decree, the Jews are

permitted to defend themselves, and Haman and his sons are hanged. Mordecai

is raised to highest station, and sends lettersunto all Jews that were in the provinces of the King ...

enjoining them that they should keep ... the days wherein the Jews had rest

from their enemies ... days turned from sorrow to gladness, from mourning

to rejoicing ... that they should make them days of feasting and gladness,

of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor.

Esther 9:20-22

The fourteenth day of the month of Adar, the day which

Haman had chosen by lots (Hebrew: purim) for the destruction of the Jews,

became a day to celebrate their being rescued. In time Purim became a holiday celebrating

salvation from evil decrees and threats of annihilation wherever and

whenever they occurred in the long history of persecution of the Jewish

people, for, as the Haggadah reminds Jews each Passover, "In every generation,

they rise up to destroy us, but the Holy One, Blessed be He, saves us from

them."The festival is not only celebrated in the home through

feasting and merrymaking but commemorated in the synagogue as well through

special additions to the liturgy and most importantly through the evening

and morning reading of the Book of Esther from a megillah scroll. The

scroll read in the synagogue contains the text alone, without illustration

or decoration, but individual Jews began to commission such scrolls with

ornamentation and illumination from the seventeenth century on in middle

and southern Europe, and later in the Near East. Some of these were

accompanied by a special sheet containing the blessings recited before and

after the reading, and most incorporated hymns.

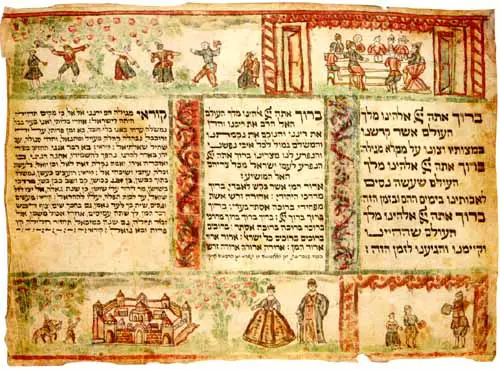

An Illuminated Megillah

Among the dozen scrolls of the Book of Esther in the

Library is one which is both illustrated and illuminated on fine vellum,

accompanied by a sheet of blessings.The blessings are the traditional ones, to which the

scribe appends a listing of those to be cursed and blessed. And in tiny

letters he offers this plea: "As thou hast taken retribution against

our ancient [enemies], do so against the evil doers now and in the future,

Amen!"The scribe also adds an acrostic poem, whose verses

begin with the letter ABRM, by the biblical commentator, grammarian, and

poet Abraham Ibn Ezra, which is included in some Sefardi liturgies to be

recited before the reading of the megillah, or on the Sabbath of

Remembrance before Purim, Shabbat Zakhor. it is found in no less

than seven manuscripts of comprehensive prayer books from Algiers and the

Yemen, and its refrain reads: "Those who read the megillah, sing

joyous songs to God, for it was a time of exultation for Israel." From

Babylonian exile to Messianic redemption is its theme; at the center of the

drama is the confrontation between Haman and Mordecai.

Some megillah scrolls are accompanied by the blessings

said before and after the reading of the Book of Esther in the synagogue. A

few have the blessings inscribed on the scroll itself, before the text;

more often they are on a small parchment of their own. The blessing

broadside which accompanies the Washington Megillah contains not only the

blessings and a liturgical poem by Abraham Ibn Ezra, but illuminations

appropriate to the Festival of Purim, some of which are copied from the

illustrated Italian Haggadot published between 1609 and 1740, (Megillah

Benedictions and Illuminations, Painting on Parchment, Italy, eighteenth

century Hebraic Section, Library of

Congress Photo).

|

Above the blessing, in pleasing colors, is a scene of

seven men and two women seated around a table at which a man is apparently

reading to them from one of several open books. Doors are open on either

side of the room. Above the poem is a scene of two men and two women

dancing in a garden; on either side is a musician playing a horn. One man

has doffed his hat. Below the blessings is a picture showing a man reading

from a book to a boy and a girl. In the center are a crowned king and queen

in royal dress. Under the poem, which ends with "May the Redeemer

arrive," is a depiction of the walled city of Jerusalem. On the way to

the city is a man on a donkey, before whom a herald sounds his shofar. It

is the Messiah about to enter the Holy City.Both the scene at the table and the Messiah at Jerusalem

are copied from the Venice Haggadah of 1609, 1629, 1695, or 1740, though

there is one more person and books have replaced food on the table.

Musicians and mixed dancing also point to the Italian provenance of the

megillah and its sheet of blessings. Cecil Roth describes northern Italian

"Jews and the ... theater, music and dance" in his The Jews

and the Renaissance. Later Italian rabbis often inveighed against their

flock for having surrendered to "the ways of the environment."

Illustrations in color accompany the text throughout,

depicting every major scene in the Esther-Mordecai Ahasuerus-Haman drama.

The illuminations, drawn with a naive charm, are appropriate to the

biblical narrative which at its heart is history recounted in the form of a

folk tale. The costumes worn by the actors in the drama, and the

illustrations depicting celebrants indicate an early eighteenth-century

Italian provenance for this charming manuscript on vellum, (The Washington

Megillah (Megillat Esther, The Book of Esther), Scroll on Parchment,

Illuminated, Italy eighteenth century Hebraic Section. Library of Congress Photo).

|

The megillah is illustrated with scenes from the

biblical narrative. Vashti, the queen, as commentators suggest, was to have

appeared without clothes. She refused, but our artist complies. The

illustrations unfold before us scenes at the court, Esther before Ahasuerus,

battles being waged, and musicians playing. The full drama of the narrative

is brought to life by the eighteenth-century north Italian landscape, its

recognizable buildings, dress, furnishings, and martial and musical

instruments-lance and viol. Ahasuerus and Vashti, Haman and Zeresh,

Mordecai and Esther become contemporaries. The illustrations do not intrude

upon the text; they give it life. Alas, we know nothing of the

illustrator-scribe, not even his name.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress, 1991).

|