History & Overview

Ravensbrück was a concentration camp for

women, which had 34 satellite divisions. Located alongside Lake Schwedt,

about 50 miles north of Berlin,

Ravensbrück opened on May 15, 1939,

and, three days later, the first group of 867 women arrived from Lichtenburg

in Saxony, a fortress that had been used as a women's camp from March 1938 until May

1939. The first prisoners were mostly of German anti-fascists, either

Social Democrats or Communists — some coincidentally Jewish, and Jehovah's Witnesses. A

high wall with electrified barbed wire enclosed the women in the camp.

|

Ravensbrück housed Jews, Gypsies, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians,

Germans and prisoners of other nationalities. Designed to accommodate

6,000 prisoners, the number of inmates grew from 2,000 in 1939 to 10,800 in 1942.

Between May 1939 and June 1944,

an estimated 43,000 women were brought to Ravensbrück. During the

next nine months, an estimated 90,000 more came. The most serious overcrowding

occurred after the evacuation of Auschwitz in January 1945,

when an unknown but significant number of Jewish women arrived at Ravensbrück.

Toward the end of the war, transports from Auschwitz and other camps in the East increased the population to its maximum,

some 32,000 women.

Human Statistics

The prisoners were organized into categories, each

with a distinctive colorcoded triangle, as well as by nationality. Political

prisoners (including resistance fighters and Soviet prisoners o fwar)

wore red triangles; Jehovah's

Witnesses wore purple triangles; “asocials” (including

lesbians, prostitutes, and Gypsies) wore black triangles; and criminals

(common criminals or those who broke Nazi imposed laws) wore green triangles.

Jewish women wore yellow triangles, but if they were also political

prisoners, they wore a red triangle and yellow triangle that formed

a Star of David, or a yellow

stripe on top of the red triangle. A letter within the triangle signified

the prisoner's nationality.

Exact statistics are impossible to obtain, because

the Nazis burned many records before they fled. The camp memorial’s

estimated figure of 132,000 includes about 48,500 Polish women, the

largest national group imprisoned in the camp. There were 28,000 women

from the Soviet Union, almost 24,000 from Germany and Austria, nearly

8,000 French women, and thousands from other countries in Europe. There

were even British and American women imprisoned at the camp. While no

exact records are available, an estimated twenty percent of the total

population was Jewish — more than 20,000 women.

Some of the Ravensbrück prisoners arrived at the

camp with their children or gave birth there. The statistics on the

arrival of children and the birth of babies are incomplete and we will

never know the full extent of the horrors inflicted on children and

newborns. Most of the newborns only lived briefly and then were murdered

by the Nazi doctors and nurses. The ledgers suggest that 882 children

were deported to Ravensbrück.

Camp Life

In the camp's early days, conditions were hygienic

and the prisoners were issued clean uniforms. By the end of the war,

conditions had deteriorated significantly. Barracks built for 250 women

later housed 1,500 or 2,000, with three to four to a bed. Thousands

of women did not even have part of a bed, and were lying on the floor,

without even a blanket. When 500 Jewish women arrived from Hungary in the fall of 1944,

they were placed in a huge tent with a straw floor and died in masses.

A plague of lice and danger of disease from the water made life in the

barracks even more unbearable.

The women were awakened for roll call by 4:00 a.m.

Before roll call, as many as 500 women stood in the latrine around three

“toilets” with no doors. After standing outside until everyone

was accounted for, they drank their imitation coffee and went off to

work. They returned to their assigned barracks for their noontime soup

and again in the evening, when the soup was repeated, On Sundays the

women were not required to work, and socialized in the barracks or outside

to the limited extent possible.

The regime was strict, punishment was inflicted, and

harsh labor was required. Solitary confinement in the dark and airless

prison cells of the “Bunker,” the usual punishment for acts

considered sabotage or resistance, was often accompanied by severe beatings

or other torture. Other routine torture methods included attacks by SS dogs. In addition to

the “Bunker,” there was a barrack separated from the camp

by a fence, which served as a punishment block. SS Reichsführer

and Head of the German Police, Heinrich

Himmler, ordered whippings beginning in April 1942.

A prisoner categorized as a criminal carried out the orders, and received

extra rations. The camp doctor was required to be present at each punishment,

to confirm it had been carried out. Himmler later ordered whipping to be used only as a “last resort.”

Slave Labor

The major private firm that used slave labor at Ravensbrück

was the Siemens Electric Company, today the second largest electric

company in the world. In a separate camp adjoining the main one, Siemens

“employed” the women to make electrical components for V-1

and V-2 rockets.

Ravensbrück was one of the Nazi's main depositories

for confiscated clothing and furs, and had an SS-owned factory for remodeling

leather and textiles, a subsidiary of Dachau Enterprises, There was

also a tailor shop that made the prisoners' striped uniforms and uniforms

for the SS, and fur coats for the Waffen-SS and the Wehrmacht, In another

shop the prisoners wove carpets from reeds. Women also did outside work,

such as construction of buildings and roads. They were used like animals,

with twelve to fourteen of them pulling a huge roller to pave the streets,

Some of the women worked in camp administration and

some worked outside the camp, for example, in the nearby town of Fürstenberg.

Those too old or disabled to perform other duties knitted for the army

or cleaned the barracks and latrines, The women usually worked for twelve

hours a day, under conditions of extreme exploitation.

Medical Experimentation

Beginning in 1942, medical experiments were

performed on the inmates; some women were infected with gas gangrene

or bacterial inflammations, while others were forced to receive bone

transplants and bone amputations. Other experiments involved sulfonamide and sterilization techniques.

Pregnant Jewish women were sent to the gas

chambers, while abortions were performed on non-Jews. The most infamous

experiments used Polish women as “guinea pigs” to simulate

battlefield leg wounds of German soldiers. Most of these women died

or were murdered afterward, and those who survived were crippled and

disfigured. .

Between 1942-1943, Ravensbrück served as a training

camp for 3,500 female SS supervisors who went on to maltreat, torture, and murder women in other

camps.

Prisoners that were sentenced to death in 1942 were sent to separate institutions or death camps. Some women, including

those incapable of work and Jewish political prisoners, were gassed

at a euthanasia center set up in the psychiatric facility of Bernberg.

By 1943, a crematorium

was built at Ravensbrück, near the camp for minors, which housed about

1,000 girls.

Slave Labor

|

Another

70,000 prisoners were brought to Ravensbrück in 1944,

most of whom were transferred to the 70 subcamps, although the main

camp housed 26,700 female prisoners in that year. An estimated 106,000

female prisoners passed through Ravensbrück by 1945.

The Nazi's utilization of slave labor to win the war

resulted in Ravensbrück’s expansion into a virtual empire

of slave labor subcamps. Products that were manufactured by women in

these subcamps included aircraft components, weapons, munitions, and

explosives.

Conditions varied from camp to camp, depending on the

size of the camp, changing circumstances as World War II progressed,

and the disposition of the personnel in charge. In addition to the Siemens

Electric Company, other prestigious and known companies that employed

slave labor in Ravensbrück's sub-camps included AEG and Daimler-Benz.

More than 55 years after the end of the war, Siemens and other companies

were finally beginning to agree to accept responsibility and pay some

compensation to their former slave laborers from Ravensbrück.

Gas Chambers

In February 1945,

a gas chamber was constructed

at Ravensbrück and, by April 1945,

between 2,200 and 2,300 were killed in the gas chamber. The majority

of those killed by gas in the camp were Hungarian, mostly Jewish, then

Polish, then Russian. Women prisoners working as scribes counted a total

number of 3,660 names on lists for “Mittwerda;” the Nazi

code name for the gas chamber. However, since some of the transports

went directly from the satellite camps to the gas chamber, the number

of women murdered in the camp's gas chamber is estimated to be 5,000

to 6,000.

The so-called “youth concentration camp”

Uckermark, less than a mile from Ravensbrück, was sometimes the

conduit to the gas chamber.

The SS used this adjacent

camp for old, sick, and weakened women who had been selected as “unable

to work;” and were sometimes given poisonous “white powder.”

Women who were sentenced to death for acts such as espionage at times

were shot in a special corridor between buildings, and other women received

lethal injections.

In March 1945,

an evacuation order was given to the inmates of Ravensbrück and 24,500

prisoners were sent to Mecklenburg. In early April 1945,

500 prisoners were handed over to the Swedish and Danish Red Cross and

2,500 German prisoners were set free.

In the summer of 1945 [sic

- probably 19431], Heinrich

Himmler issued

a directive to create brothels in concentration

camps. Eighteen to twenty-four women

were taken from Ravensbrück

to each camp where a brothel was established.

The women were all “volunteers.”

They were promised they would have to work

for six months.

The prisoners could do little to fight back against

their captors, but they did engage in various forms of spiritual resistance,

such as holding classes in language, history, and geography classes;

improvising theater and music; drawing the reality of camp life; and

sharing recipes and preparing imaginary meals, Through such activities,

the women helped each other survive. While there could not have been

armed resistance under the circumstances of Ravensbrück, there

was sabotage during production of rocket components at the Siemens factory,

There were also efforts by prisoners who worked in the offices to keep

secret records of arrivals, punishments, and deaths, During the early

years of the camp, there was even a secret newspaper.

Liberation

The Soviets liberated the camp on April 29-30, 1945,

and found approximately 3,500 extremely ill prisoners living at the

camp; the Nazis had sent the other remaining women on a death march.

It is estimated that 50,000 women died at Ravensbrück, either from harsh

living conditions, slave labor or were put to death.

Count

Folke Bernadotte, vice president of the Swedish Red Cross, had convinced Himmler to allow the International

Red Cross to rescue some prisoners from Ravensbrück and other camps

and bring them to Sweden, The

Swedish Red Cross was first allowed to rescue Scandinavians on March

5, followed by women from France, Poland, and the Benelux countries.

Through the intervention of the Swedish section of

the World Jewish Congress, Bernadotte requested that Jewish prisoners

also be sent to Sweden. Himmler agreed, and between April 22 and April

28, about 7,500 women — an estimated 1,000 of them Jewish —

were liberated from Ravensbrück. They were then ferried from Copenhagen

to Malmö in neutral Sweden, Once there, they received clothing,

food, and medical attention and were then sent to recuperate in different

locations. Afterward, most of the non-Jewish women returned to their

homelands. The Jewish women sought out surviving family members in their

former homelands, but most immigrated to Israel or the Americas, and some settled in Sweden.

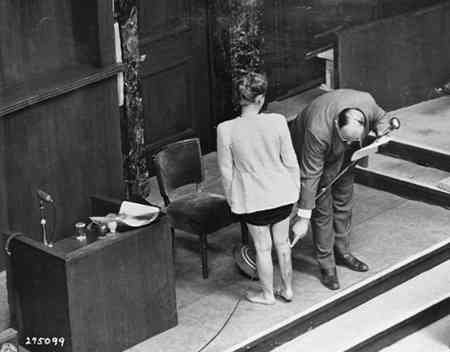

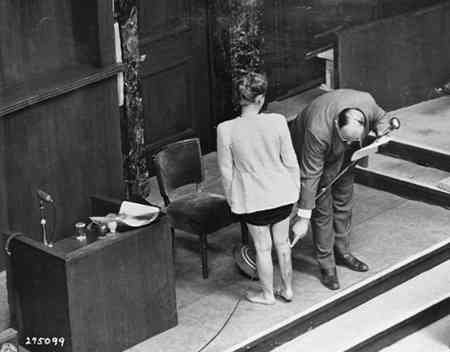

Jadwiga Dzido shows her scarred

leg to the court at the Doctors Trial, while expert witness Dr. Alexander

explains the nature of the medical experiment performed on her at Ravensbruck.

Jadwiga Dzido shows her scarred

leg to the court at the Doctors Trial, while expert witness Dr. Alexander

explains the nature of the medical experiment performed on her at Ravensbruck. |

War Crimes Trials

Trials for the people charged with war crimes at Ravensbrück

were held in Hamburg, in the British Zone. Many of the war criminals

were doctors and nurses who participated in the medical experiments.

Dorothea Binz was the brutal SS head overseer of Ravensbrück from August 1943 until April 1945.

She received a death sentence and was executed at the Hameln Prison

on May 2, 1947. Irma Grese was a “graduate” of the Ravensbrück training camp,

who was sentenced to death by hanging and executed in 1945 for her crimes

at Auschwitz. Hermine Braunsteiner

Ryan, a guard and supervisor of guards at Ravensbrück, Auschwitz,

and Majdanek entered

the United States after World

War II and was extradited to Germany in 1981 by the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

The camp was generally off limits for visitors from

the West until after the Berlin wall fell in November 1989. The original

barracks were razed by the Soviet Army after World War II, and new barracks

were built for the Soviet troops stationed in the camp until 1993. They

were there as part of the Soviet Union's Cold War antimissile program.

During this time, the former SS headquarters, punishment block, and crematorium housed memorial exhibits.

After the reunification of Germany, the camp's site was refurbished

and readied for the April 1995 ceremonies that marked the fiftieth anniversary

of liberation. Although

the lake looks picturesque, it contains the women’s ashes from

the camp crematorium’s three ovens.

Sources: Center

for Holocaust and Genocide Studies; Holocaust. Israel Pocket Library, Jerusalem: Keter Books, 1974; Kogon, Eugen. The

Theory And Practice Of Hell. NY: Berkley Publishing Group,

1998, p. 135; Encyclopedia

Britannica; Encyclopedia

of the Holocaust; Simon

Wiesenthal Center Online.

1Heinrich

Himmler developed an idea to provide hardworking

prisoners

with incentives in the camp system. He expressed his

thoughts in a

letter to Otto Pohl of the SS Economic Division on

March 5, 1943: “I consider it necessary to provide

in the most liberal way

hard-working prisoners with women in brothels.” Pohl,

in turn, directed these instructions to commandants

such as

Rudolf Höss at Auschwitz. Brothel vouchers were

to be issued only to

prisoners of special value—and certainly not

to Jews.

(Source: Nuremberg Trial Proceedings)

|