Background & Overview

(June 6, 1944)

The plans to invade Nazi-occupied Europe through the beachheads of France sat in front of General Eisenhower. On the evening of June 5, 1944, the wind was blowing at 15

to 20 knots and six-foot waves were roiling the ships, but the Royal

Air Force (RAF) predicted the skies would be clear the next

day. Conferring with his colleagues, Eisenhower got conflicting

advice - Generals Bradley and Montgomery

wanted to go ahead; the Air Force and Navy generals preferred

to wait.

After a few moments of deliberation, Eisenhower said three

words that would change history: “Okay, let’s go.”

- Attacking France

- Omaha Beach

- Gold Beach

- Sword Beach

- Hitler's Mistakes

Attacking France

On the morning of June 6, 1944, Eisenhower released the following order, alerting the Allied armies of the green light for war:

“Soldiers, sailors, and airmen of

the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the

Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The

eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving

people everywhere march with you.”

With General Eisenhower's go-ahead, the BBC broadcast a coded message that instructed

members of the French resistance to cut railway lines throughout the

country. Nearly all of those targeted were successfully severed.

The attack began with more than 1,000 RAF bombers

attacking coastal targets. This attack was followed by 18,000 paratroopers

being dropped inland to capture key bridges and roads and cut German

communications. The British Sixth Airborne Division suffered few casualties

and succeeded in capturing bridges at the Orne River and the Caen Canal.

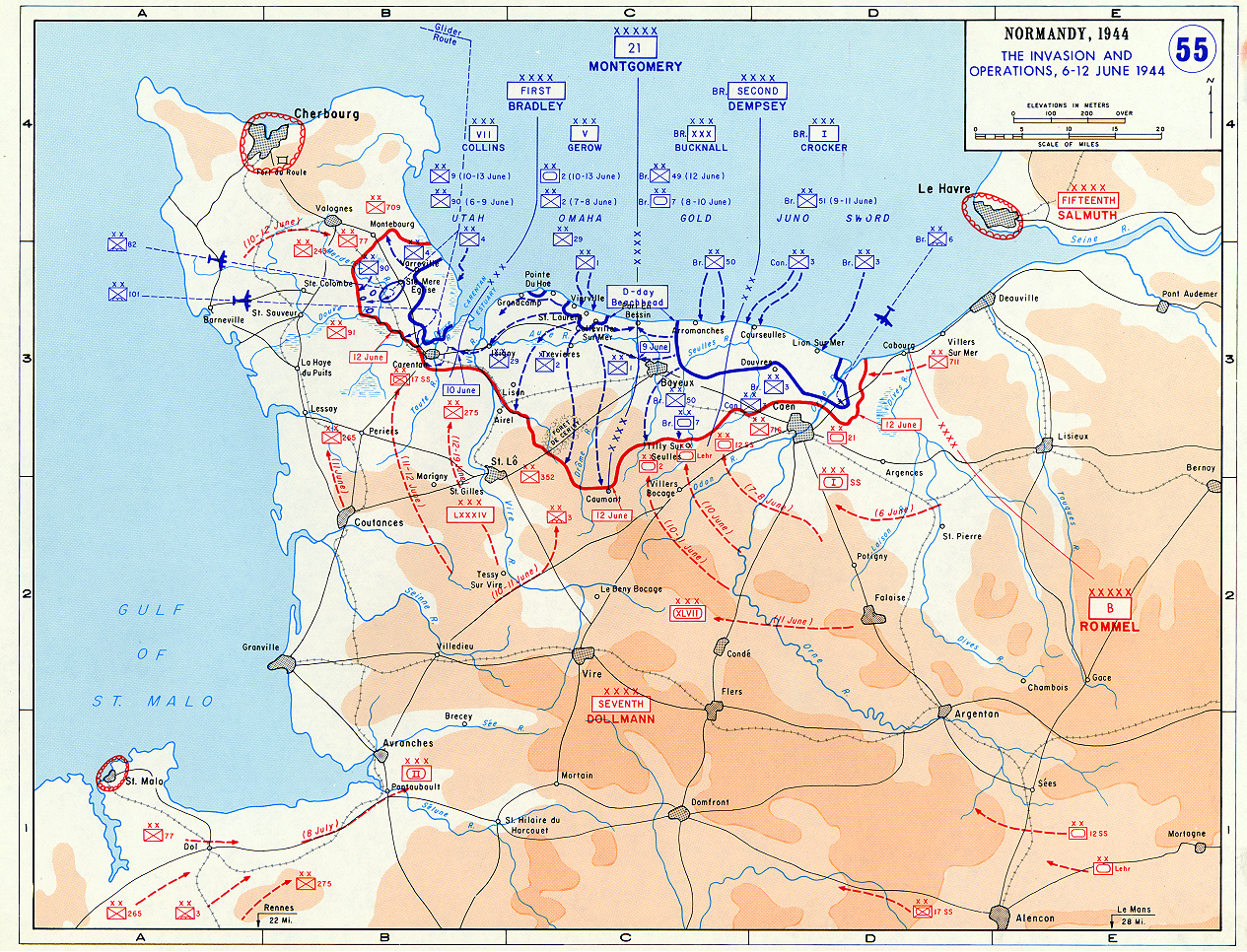

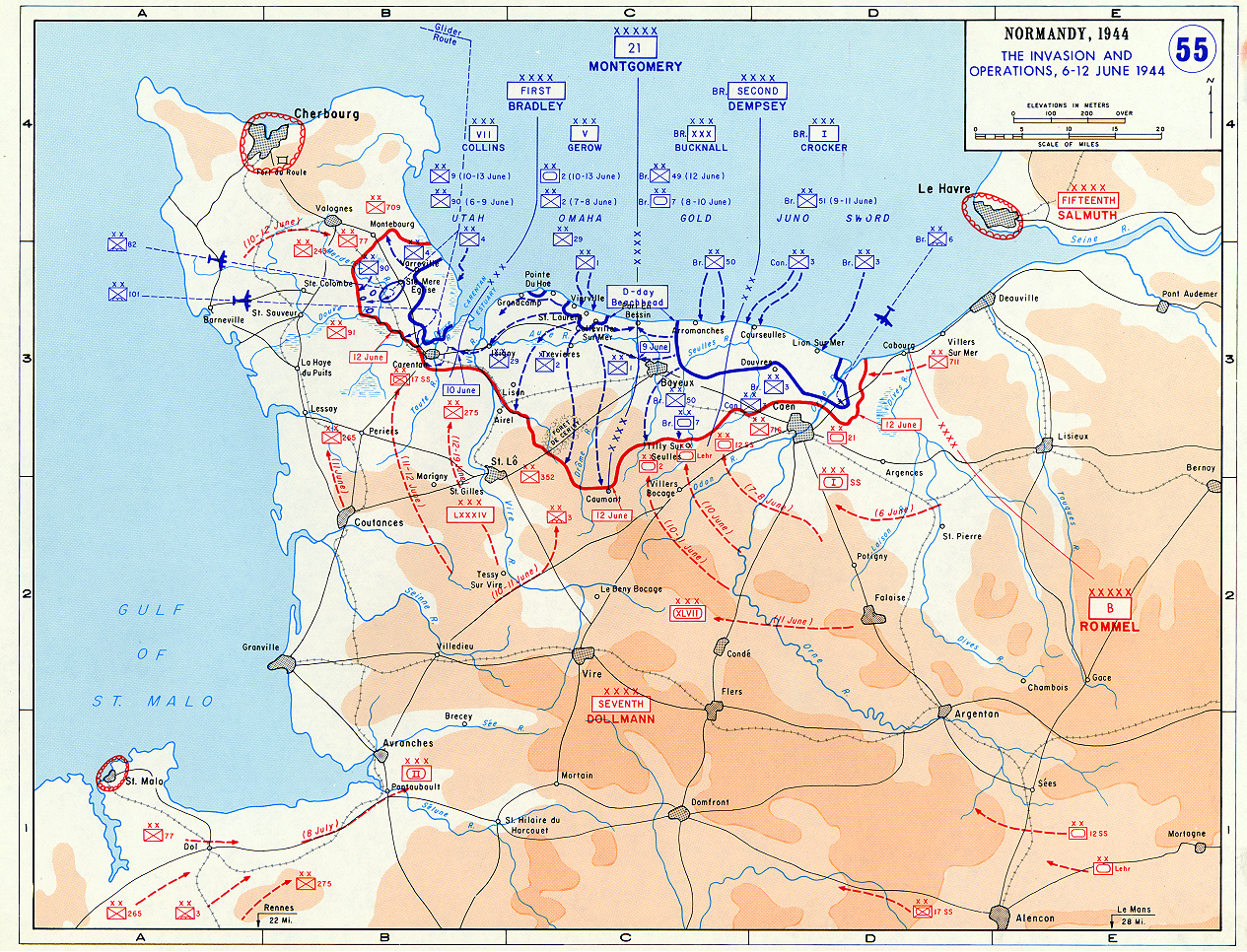

Allied Invasion of Normandy (Click to Enlarge)

Allied Invasion of Normandy (Click to Enlarge) |

The Americans had a harder time. Their 101st and 82nd

Airborne Divisions missed their drop zone and were scattered. Many men

drowned when they landed in the water. The dispersion of the Americans

helped confuse the Germans, but it also meant that troops who survived

the jump (and many didn’t) were isolated and easier to kill or

capture. But in the end, they played a major role in the securing of

Normandy by opening the way inland for the infantry, destroying much

of the German artillery aimed at the beaches, and blocking avenues for

potential counterattacks. Dying was not a danger for the dummy paratroopers

— literally dolls dressed up like soldiers — that were also

dropped away from Normandy to deceive the Germans as to the location

of the attack.

Minesweepers cleared lanes in the English Channel for

the transports. The beaches were 60 to 100 miles away when the armada

of nearly 7,000 ships left from ports such as Portsmouth, Southampton,

Chichester, and Falmouth. Soon that 100 miles would be covered with

59 convoys that included 4,000 landing craft, 7 battleships, 23 cruisers,

and 104 destroyers.

German torpedo boats out of the port at Le Havre were

the first to encounter the Allied forces, but they were quickly driven

off. Having spotted the invasion fleet, German coastal batteries began

firing at the approaching ships. At the same time, Allied warships began

bombarding the beaches, destroying bunkers, setting off land mines,

and destroying obstacles in the path of the landing parties.

To prepare for the landing of troops, the air force

and navy bombarded German positions, and continued their attacks throughout

the day. Meanwhile, paratroopers blocked any potential counterattackers

and knocked out the artillery batteries that covered the beach.

The first troops hit the beaches about 6:30 A.M.,

with 23,000 men rushing onto Utah Beach. Though certainly scared to

enter combat, which most were facing for the first time, the soldiers

were so terribly seasick from the rough crossing that they were actually

anxious to get off the boats.

“We want this war over with. The quickest

way to get it over with is to go get the bastards who started it.

The quicker they get whipped, the quicker we can go home. The shortest

way home is through Berlin and Tokyo. And when we get to Berlin,

I am personally going to shoot that paper-hanging son-of-a-bitch

Hitler.”

— General Patton, Speech to the Third

Army (June 5) |

Almost nothing went according to plan. Few of the landing

craft arrived at the time they were supposed to, and none placed their

troops at the designated target. The landing craft were buffeted by

wind and waves and had to evade a network of thousands of mines, which

sank several of the ships that were assigned to guide those that followed.

General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the son of the former

president, was one of the first ashore. He had lobbied to lead his troops

in to boost their morale, but had a tough time persuading his superiors

to let him go. Besides his rank and lineage, Roosevelt had a heart condition

and walked with a cane, but he would not be deterred from the mission.

Looking every part the Hollywood commander— Roosevelt did not bother

with a helmet, he wore a wool-knit hat instead— he ignored the shooting

around him and calmly walked across the beach to huddle with commanders.

Since the invasion force had landed in the wrong place, they had to

decide whether to stick to the original plan and have the remaining

troops try to land in the target area or improvise and head inland from

where they were. Roosevelt is said to have made the decision, “We’ll

start the war from right here.”

Most of the German defenders (many of whom were not

German, but soldiers forced into the army from occupied countries) either

surrendered or withdrew inland. The American forces quickly secured

the area and, within a few hours, supplies and additional troops were

also coming ashore. Soon the biggest problem for the Americans at Utah

was managing the traffic jam of men and material.

Omaha Beach

Rommel knew that if an attack came at Normandy, at least part of the invasion

force would try to land on the sandy beach the Allies designated as

Omaha. This beach was the largest landing area (six miles) and the most

vulnerable: 100-foot nearly perpendicular cliffs overlooked the beach.

To prepare for a possible attack, the Germans had mined the waters offshore,

littered the beach with obstacles, and placed heavy guns on the cliffs

overlooking what amounted to a shooting gallery below. And, in fact,

when the defenders saw the first landing parties, they thought they

were crazy.

American soldiers landing at Omaha Beach

American soldiers landing at Omaha Beach |

The Allies were confident that the air and naval bombardment

would soften up the defense, that the German soldiers would be from

a low-quality division, and that the 40,000 troops assigned to take

the beach would overwhelm the defenders. Instead, the defensive force

the Americans confronted, an elite German infantry division, was far

stronger and better trained than expected. Heavy clouds protected the

German defenders from Allied bombers, who dropped their payloads in

fields beyond the beachfront, and the poor visibility also prevented

offshore guns from initially offering much support.

With the exception of one unit, the wind and tide

caused the landing craft to miss their objectives. Instead of distributing

troops across the beach, they landed in bunches that became easier targets

for the German gunners. Many soldiers were killed before they could

fire a shot in the war. More than two-dozen of the special amphibious

Sherman tanks made for the invasion immediately sank upon debarking

the transports, taking their crews to the bottom. These were just a

fraction of the hundreds of vehicles of all types that never reached

the beach or were destroyed soon after they got there. Instead of 2,400

tons of supplies being brought ashore, only 100 tons made it.

In writing, much of the fighting can only be described

in a sterile fashion that doesn’t capture the horror of combat.

Omaha Beach was as hellish as any battle of the war. The first landing

parties, seasick from the rough crossing, were literally ripped apart

by mines, artillery, and machine-gun crossfire.

Many soldiers drowned in deep water before their craft

were close enough to the beach. Others struggled even in shallower water,

fighting the tide and the burden of carrying packs and guns, wearing

heavy boots and steel helmets, and then adding the additional weight

of their drenched uniforms. Helpless in the water, still more men were

killed before they could stagger ashore. The noise was deafening, and

the cries of the wounded sickening. The beach offered no cover, the

only place to go was forward, and the chances of making it across in

the early stages were practically zero. Waves of landing craft continued

to drift ashore, many exploded by shells or mines, and the numbers of

Allied soldiers and casualties piled up. The veterans of the landing

on Omaha would later reminisce that it was a miracle they managed to

get on the beach, let alone survive on it or advance beyond it.

Given the enormous naval armada offshore and the Allied

dominance of the air, it is reasonable to ask why the German forces

couldn’t have been decimated by strafing planes, bombers, and

shells from the navy’s big guns. Those assets did not play as

large a role as they might have for several reasons. Perhaps the most

important is that once the soldiers were on the beach, neither the air

force nor the navy had the accuracy to hit only the enemy targets, and

it was feared that too many friendlies could be hit by accident. The

navy provided invaluable support, but it was limited because so many

radios were lost or disabled in the landing that troops on the beach

could not communicate with the ships and direct their fire. The air

force ensured the Germans couldn’t put planes in the air to harass

or otherwise threaten the invasion, but Allied planes couldn’t

support the fight on the beach; their main contribution would be in

destroying targets inland that would help the advancing troops after

they got past the beaches.

The landing stalled and the order was given to cease

landing. General Bradley thought the landing had been a disaster and

the troops might have to withdraw. All organization fell apart as soldiers,

boats, and bodies jammed the single narrow channel engineers were able

to clear among the German mines and obstacles. Trapped behind a low

shelf halfway across the beach, under withering German fire from above,

isolated groups and individuals with no choice but to get off the beach

gradually fought their way forward and eventually took key points at

each end of the beach. It took several hours, and heavy navy bombardment,

to secure the beachhead, as well as a courageous effort by Army Rangers,

men of C Company, and the 116th regiment to scale the surrounding cliffs

with rope ladders to take out the guns guarding the coast.

Gold Beach

The British troops landed at 7:20 on Gold Beach, where

their experience was completely different from that of the Americans

at Utah and Omaha. Unlike those landed sites, the British had little

actual beach to cross. Once they surmounted the seawall and an antitank

ditch, they were into villages with pave streets. Beyond the villages

were mostly large wheat fields. They also faced almost no enemy fire

and had an orderly landing that went largely according to plan. A total

of 25,000 troops stormed Gold at a cost of 400 casualties. By the end

of the day, the British had advanced five miles beyond the coast.

A Canadian force was assigned the task of taking Juno

beach. This all-volunteer force was well-trained and highly motivated

because of a desire to avenge a disastrous defeat during the attempted

assault on the port of Dieppe in August 1942.

As in the case at the other landing sites, the Canadians

expected the defense to have been significantly degraded by air force

bombing, but despite the heaviest bombardment of the war during the

hours preceding the invasion, not a single fortification on Juno was

destroyed. Still, the 2,400 Canadians who came ashore overwhelmed the

400 German defenders, who were not front-line troops, but mostly Poles

and Russians who had been forced to serve a regime they did not believe

in.

Sword Beach

While much of the preinvasion actions designed to knock

out German defenses and make the beach landings easier did not go according

to plan, the airborne plan to take out the German guns covering Sword

beach did succeed. Not all the guns were taken out, and the invasion

force did face formidable mine fields, antitank ditches, and other fortifications,

but the paratroops did succeed in significantly degrading the enemy

defenses. This allowed 29,000 British soldiers to storm the beach at

a cost of 630 casualties. As in the case of the other beaches, the troops

overcame the initial defense and then began to move inland, but failed

to get as far as the D Day planners had hoped.

By 10:15 A.M., Rommel had learned that the Allies

had landed and rushed back to France. Hitler had ordered him to drive the invaders back into the sea, but still had

not given him the military resources he needed to do so. One of the

strongest panzer divisions, equipped with new, state-of-the-art Tiger

tanks, was sent to reinforce the defenders at Normandy, but its trip

from Toulouse was repeatedly delayed through the sabotage efforts of

British agents and French partisans, who turned what should have been

a 3-day race to the front into a 17-day crawl.

Another panzer division tried to split the British

and Canadian forces by shooting through the gap between Sword and Juno.

Had it succeeded in reaching the sea, it might have caused serious trouble,

but the British were able to neutralize the German force before it could

do any serious damage.

In the terrifying first hours making their way under

fire from the stormy sea to shore, across a front of more than 50 miles,

the Allies suffered surprisingly few casualties. On that first day,

roughly 175,000 soldiers had come ashore and approximately 2,500 had

been killed. The Americans had suffered the fewest casualties (dead

or wounded) on Utah Beach, approximately 300, but also the most, 2,400

(our of 40,000 who went ashore), on Omaha. In the first two days, the

number of men and vehicles the Allies got across the Channel was well

below what was planned; still, Eisenhower was happy the deception had

worked, and the Germans were unable to stop them on the beaches.

Once the initial assault succeeded, the Allies had

an opportunity to press their advantage and exploit the Germans’

confusion, but they did not advance as far as expected. In fact, the

deepest penetration, by the Canadians at Juno, was only about six miles.

Besides German opposition, one of the principal reasons the penetration

was not greater was that soldiers felt so satisfied with what they’d

just accomplished — and thankful that they had survived.

Hitler's Mistakes

The Germans had made numerous fatal miscalculations.

The most important was their conviction that the invasion would be elsewhere,

so they were caught by surprise at Normandy. At the end of D Day, most

of their forces were still arrayed in preparation for an invasion at

Pas-de-Calais.

General Jodl believed it would take the Allies as long as a week to put three divisions

into France, but the Americans had accomplished this on Utah beach alone

in a single day. Communication was poor, so the Germans were confused

throughout the attack as to exactly what was happening where and Rommel,

the architect of the defense plan, was in a car driving through France

and incommunicado during several crucial hours.

As in the case of the Eastern Front, the German high

command was also hamstrung by Hitler’s distrust of his generals

and their fear of acting without his approval. This proved disastrous

on D Day when Rundstedt ordered two panzer divisions to Normandy, but

first requested Jodl’s approval. Jodl told Rundstedt Hitler was sleeping. No

one had the courage to wake Hitler for approval and since he slept in

that day, the tanks were not moved into position.

The Germans also made the mistake of trusting their

own version of the Maginot Line, the Atlantic Wall, to stop the Allied

invasion rather than the deployment of their best troops. They had indeed

erected a formidable defense of trenches, mines, barbed wire, and other

obstacles, but it took the Allies less than a day to breach it, and

then the “wall” was useless.

Rather than assign their crack troops to protect the

wall, the Germans had also decided to hold them in reserve or had them

deployed elsewhere. Instead, they relied on poorly trained conscripts

and POWs from territories they’d conquered who had little or no

motivation to fight for Hitler, and were no match for the Allied troops

who were superbly trained and believed they were fighting to keep the

world free.

Monitoring German military messages after the invasion,

the British picked up the crucial piece of information that the Luftwaffe

was dangerously short of aircraft fuel. Knowing this, war planners made

Germany’s synthetic oil factories their top priority for air strikes

as soon as Overlord could spare

the planes.

Within a week, American and British forces linked

up, clearing the beachheads. With this done, the Seventh Corps, under

Major General J. Lawton Collins, moved on Cherbourg and took the city

on June 27. This port was meant to receive men and supplies, but it

took several weeks for the damage to be sufficiently repaired. The delay

was a factor in stalling the later offensive, but once the port was

fully operational, it was the entry point for more than half of all

American supplies sent to France.

The victory at Cherbourg was important for demoralizing

the Germans, particularly after Hitler had ordered the port held at all costs. Afterward, Rommel and von Rundstedt went

to see Hitler, to ask again for more troops and equipment, and to find

out how he intended to win the war. Hitler’s reaction was to deny

the requests, sack von Rundstedt, and replace him with Field Marshal Gunther Hans von Kluge.

Sources: Bard, Mitchell G. The

Complete Idiot's Guide to World War II. 2nd Edition. NY: Alpha

Books, 2004. |