Charting the Holy Land: Journey Across the Sinai

The "Terra Sancta quae in Sacris Terra Promissionis olim Palestina" map of Willem Blaeu affords the armchair pilgrim an opportunity to accompany the Children of Israel in their journey across the Sinai wilderness, to reexperience their adventures there. Delicately engraved tiny vignettes which demand a sharp eye or a magnifying glass abound, the route marked out in events, not in numbers as in the map of Ortelius. The departure is from Rameses, and the cartographer recommends that we consult Exodus 12. A bit further on, we camp at Succoth, then at Etham, which is where the Lord began to go before the wanderers, "by day in a pillar of cloud ... and by night in a pillar of fire." Cloud and fire are made more vivid still by the illuminator whose colors remain as bright today as three hundred years ago when he first applied them. We march across the Red Sea and see the pursuing Egyptian army sinking under the waves, only their spears visible above the waters. in the wilderness of Zin, we gather manna with the Children of Israel and welcome the soaring quail "who came up and covered the camp." We see Moses standing on a rocky promontory, his arms held aloft by Aaron and Hur. Below, as the map states, are armies arrayed for, Bellum contra Amelecitas, the war against the Amalekites.

|

We are at Sinai. Above us, on the mountain's summit, haloed in a cloud of glory, is Moses, holding aloft the Tablets of the Law. On the plain below, the Children of Israel prance around a golden calf. We near the borders of the Promised Land. Two men are returning from spying out that land, carrying a huge vine heavy laden with its grapes. We remember the ten spies who warned against entering the land. The journey turns once more to the wilderness, for forty years, till a new, more courageous generation arises.

At long last we are at Mt. Nebo. Hic Mortuus Moyses we read, "Here Moses died." The tiny dots which mark the route of the journey take us to the River Jordan which we cross to inherit the land Moses could see only from afar, a land which, on this map, stretches all the way to Tripoli. Here, the delineation of historic events comes to an end. Buildings denoting Jerusalem, Hebron, Samaria, and other cities can be seen, but no historic incidents, no people; as its title indicates, it is a map of the Terra Promissionis, the Promised Land. The Children of Israel having entered, it is no longer that, the promise having been fulfilled.

The orientation is to the west. At the top is the Mediterranean. A ship is caught in a storm. Near it is a "great fish" but quite benign. Jonah is nowhere to be seen. The cartouche has the classical depictions of Moses and Aaron. The Lawgiver, rod in hand, holds the Tablets of the Law; the High Priest, in full regalia, head turbaned, the Urim and Tumin breastplate on his chest, holds a censer billowing fragrant smoke.

This charming map was drawn in 1629 and incorporated into Blaeu's Atlas Maior, Amsterdam, 1662-65. The Library has a superb copy, whose paper remains crisp and whose colors have retained their freshness, with glinting gold highlights.

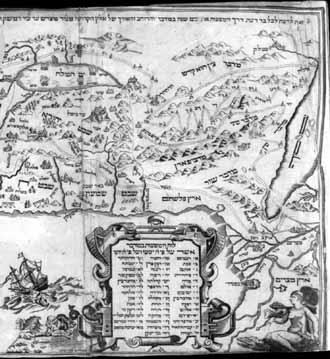

A map published in Amsterdam sixty-five years later also features the Children of Israel wandering in the wilderness. But while we can only conjecture why Ortelius and Blaeu chose to emphasize the wandering in their maps, it is obvious why Abraham bar Jacob did so. He intended his map to be inserted in an edition of the Passover Haggadah for which he had prepared a new set of illustrations. His map was to illustrate an aspect of the Exodus which the Haggadah celebrates, the journey from Egypt to the Promised Land. The course of the wandering is laid out in dotted parallel lines, each year of the journey marked by a Hebrew number, the resting places listed by identifying numbers in the cartouche.

|

|

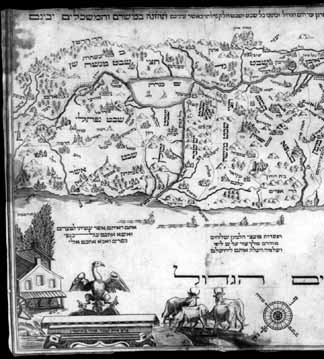

By far the most popular Hebrew map of the Holy Land is the one drawn by the proselyte Abraham bar Jacob for the Amsterdam 1695 edition of the Passover Haggadah, for which he also prepared the pictorial engravings. We show the one reproduced in a 1781 edition of the Haggadah published by the widow and orphans of the late Jacob Proops, printers in Amsterdam. An ownership inscription reads: "Samuel Hart, Passover Book, January 28th 1784." A resident of Halifax, Nova Scotia, at the end of the eighteenth century, Hart was a member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1793 to 1799, the first Jew to be a member of a legislative body in Canada, (Haggadah shel Pesah, Amsterdam, 1781. Hebraic Section, (Library of Congress Photo)

The orientation is to the southeast. At bottom right is a female figure on the back of a crocodile, protecting herself from the sun with an open parasol. The inscription above her indicates both the geographic location and what the figure represents, "The Land of Egypt." In the center of the sea is a large fish, mouth open ready to swallow a man being cast from a ship, but a further depiction shows Jonah spewed out of the fish's mouth, safe on dry land-saved! At bottom left are illustrations touching upon the dual theme of this map as stated by an inscription at its top: "This [map] is to inform every knowing person of the route of the forty-year journey in the desert, and the breadth and length of the Holy Land from the River of Egypt to the City of Damascus and from the Valley of Amon to the Great Sea, and within the land, the territory of each tribe as your eyes will see, and the wise will understand." An eagle with wings outstretched under a verse stating, "Ye have seen what I have done to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on the wings of eagles, and brought you unto myself" (Exodus 19:4), and leafy trees, marked "The Festival of Sukkoth," touch upon the Exodus theme. Four cows with the inscription "milk," and three honeycombs with the word "honey" refer to the Land of Israel, a "Land of milk and honey." The theme of the land dominates the map, an emphasis fortified by a vignette not found in other maps, sailing ships towing barges. An inscription describes them as "Rafts of cedars of Lebanon, sent by Hiram, King of Tyre, on the sea to Jaffa, from whence Solomon brought them up to Jerusalem." We have thus the introduction of a later period of Jewish history and a foreshadowing of later Jewish cartographers' interest in the city of Jerusalem and the Temple of Solomon.

The cartographer's name at the bottom is Abraham bar Jacob. A Christian pastor in the Rhineland who had converted to Judaism and become a copper engraver in Amsterdam, he provided the illustrations for the Haggadah of 1695, which have appeared in many Haggadot up to the present day. The map is in Hebrew. A special feature of this map, that seems heretofore not to have been noticed, is bar Jacob's treatment of the Exodus not as leaving but as returning. He depicts the traditional Goshen to the Jordan route, but adds another one beginning in Hebron and ending in Goshen, the route the family of Jacob took to Egypt. The route is marked by the only historical vignette on the map, a wagon representing those which Joseph sent to bring his family to Egypt. The Library has a fine copy of the 1695 Haggadah with a map; the map displayed here is from its 1781 edition.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).