|

[By: Rebecca Weiner]

Before the outbreak of World War II, more than 3.3 million Jews lived in Poland, the largest Jewish population of Europe and second largest Jewish community in the world. Poland served as the center for Jewish culture and a diverse population of Jews from all over Europe sought refuge there, contributing to a wide variety of religious and cultural groups. Barely 11% of Poland's Jews - 369,000 people -survived the war. To view the full list of Jewish communities in Poland destroyed by the Holocaust, please click here. Today, approximately 3,200 Jews remain in Poland.

- Early History Through the Middle Ages

- Colonization of the Ukraine

- Chmielnicki Revolt & Rise of Hasidism

- Rise of the Haskalah

- After World War I

- The Holocaust

- Post-World War II & Communist Era

- Present Day Poland

Early History Through the Middle Ages

|

There is no specific date that marks Jewish

immigration to Poland. A journal account of Ibrahim ibn Jakub, a

Jewish traveler, merchant and diplomat from Spain mentions Cracow and the First Duke of Poland, Mieszko I. More Jews arrived during the

period of the first Crusade in 1098, while leaving persecution in

Bohemia, according to the Chronicler of Prague. There is also

archeological evidence, coins from the period with inscriptions in

Hebrew, revealing that other Jewish merchants traveled to Poland in

the 12th century. The coins may have belonged to 12th century Jewish traders, Holekhei Rusyah (travelers to Russia).

While persecution took place across Europe during

the Crusades, in the 13th century, Poland served as a haven for European Jewry because of its

relative tolerance. During this period, Poland began its colonization

process. It suffered great losses from Mongol invasions in 1241 and

therefore encouraged Jewish immigrants to settle the towns and

villages. Immigrants flocked to Poland from Bohemia-Moravia, Germany,

Italy, Spain and colonies in the Crimea. No central authority could

stop the immigration. Refugees from Germany brought with them German

and Hebrew dialects that eventually became Yiddish

Jews were treated well under the rule of Duke Boleslaw

Pobozny (1221-1279) and King Kazimierz Wielki (1310-1370, aka King Casimir the Great ) because the now-decentralized nature of Polish polity saw the nobles forced to run their own areas and therefore the Jews- a group with commercial and administrative experience - were fought over to attract to the various townships.

In 1264, Duke

Boleslaw issued the "Statute of Kalisz," guaranteeing

protection of the Jews and granting generous legal and professional rights, including the ability to become moneylenders and

businessman. King Kasimierz ratified the charter and extended it to include specific points of protection from Christians, including guaranteed prosecution against those who "commit a depredation in a Jewish cemetery" and banning people from "accusing the Jews of drinking human blood."

Freedom of worship and assembly was also granted to the Jews, which helped lay the

seeds for the foundation of Hasidism and other

Jewish movements. One of the great sages of the time, Jacob Savra of Cracow,

was extremely learned in Talmud,

his opinions differed from Talmudic authorities in Germany and

Bohemia.

In the 14th century, opposition arose

to the system in which Jews owned land that would be used as

collateral for loans. By the mid-1300's, hatred of the Jews existed

among the nobility. According to the Chronica Olivska, Jews

throughout Poland were massacred because they were blamed for the

Black Death. There were anti-Jewish riots in1348-49 and again in 1407

and 1494 and Jews were expelled form the city of Cracow in 1495.

During the 14th and 15th century, Jews were active in all areas of trade, including cloth,

horses, and cattle. By the end of the 15th century, Polish

Jews began trading with Venice, Feodosiya and other Genoese colonies

in the Crimea, as well as with Constantinople. Accusation were made

against the Jews claiming unfair competition in trade and crafts. Due

to these complaints, in 1485, Jews were forced to renounce their

rights to most trades and crafts. These accusations may have led to

the Jewish expulsion from Cracow in 1495.

By the mid-16th century, eighty percent of the

world’s Jews lived in Poland. Jewish religious life thrived in many

Polish communities. In 1503, the Polish monarchy appointed Rabbi

Jacob Polak, the official Rabbi of Poland, marking the emergence of

the Chief Rabbinate. By 1551, Jews were given permission to choose

their own Chief Rabbi. The Chief Rabbinate held power over law and

finance, appointing judges and other officials. Some power was shared

with local councils. The Polish government permitted the Rabbinate to

grow in power, to use it for tax collection purposes. Only thirty

percent of the money raised by the Rabbinate served Jewish causes,

the rest went to the Crown for protection. In this period

Poland-Lithuania became the main center for Ashkenazi Jewry and its

yeshivot achieved fame from the early 1500's.

One the great talmudic scholars of the 1500's was Moses

ben Israel Isserles (1525-1572). He founded a religious academy

in Cracow. Beyond Talmudic

study, he was also familiar with many of the Greek philosophers and

was one of the forerunners of the Jewish

enlightenment.

Colonization of the Ukraine

In the 16th century, Jews also thrived

economically and took part in the settler movement of Poland. In

1569, Poland and Lithuania unified and then Poland annexed the

Ukraine. Many Jews were sent to colonize these territories.

Polish nobility and landowners and Jewish

merchants became partners in many business enterprises. Jews became

involved in the wheat export industry, which was in high demand

across Europe. The Jews built and ran mills and distilleries,

transported the grain to the Baltic Ports and shipped it to the West.

In return they received wine, cloth, dyes and luxury goods, which

they sold to Polish nobility. The roles of magnates, middleman and

intermediaries with the peasants were held by the Jews.

Jews created entire villages and townships,

shtetls. Fifty-two communities in Great Poland and Masovia, 41

communities in Lesser Poland and about 80 communities in the Ukraine

region.

From the 16th to 18th century, Jews enjoyed a measure of self-government — the Council of

Four Lands (Va’ad Arba Artsot) — which served as a Jewish

Parliament. Ordinances of the Council of the Lands revealed the

ideals of widespread Torah study. Jews were active at all levels of society and politics. Almost

every Polish magnate had a Jewish counselor, who kept the books,

wrote letters, and managed economic affairs.

At the end of the 1600's, Poland-Lithuania was

involved in a war against Sweden and another war against Moscow. The

wars weakened Poland’s food-exporting industries and strained the

Polish nobility, who then put pressure on the Jews and raised

tariffs. In turn, the Jews put pressure on the local peasants.

Chmielnicki Revolt & Rise of Hasidism

In 1648, a Ukrainian officer Bogdan Chmielnicki,

with the support of the Tatar Khan of Crimea, roused the local

peasants to fight with him and the Russian Orthodox Cossacks against

the Jews. The first wave of violence in 1648 destroyed Jewish

communities east of the Dnieper River. Following the violence,

thousands of Jews fled west, across the river, to the major cities.

The Cossacks and the peasants followed them; the first large-scale

massacre took place at Nemirov (a small town, which is part of

present-day Ukraine). It is estimated that 100,000-200,000 Jews died

in the Chmielnicki revolt that lasted from 1648-1649. This wave of

destruction is considered the first modern pogrom.

Ba'al Shem Tov

Ba'al Shem Tov |

The revolts left much of the Jewish population impoverished.

In the 1660's, many Polish Jews became caught up in the fervor and excitement

of Shabbetai Zevi and,

a century later, Jacob Frank.

According to Hasidic tradition,

in southeast Poland, in the region of Podolia, Israel

ben Eliezer Ba’al Shem Tov (otherwise known as the Ba’al

Shem Tov or Besht) was born in 1699. It was said that he was a Ba’al

Shem (miracle worker), curing Jews with amulets and charms. The Ba’al

Shem Tov reached out to the masses and peasant Jewry. Hasidism flourished

after his death and was spread by Rabbi Dov Baer, the Maggid (storyteller)

throughout Eastern Europe.

Rise of the Haskalah

There were three partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793

and in 1795. Poland was divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria; Poland-Lithuania

no longer existed. The majority of Poland’s one-million Jews became

part of the Russian empire. Poland became a mere client state of the

Russian empire. In 1772, Catherine II, empress of Russia; discriminated

against the Jews by forcing them to stay in their shtetls and barring

their return to the towns they occupied before the partition. This area

was called the Pale of Settlement.

By 1885, more than four million Jews lived in the Pale.

During this period, the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) spread throughout Poland. Supporters of the

Haskalah movement wanted to reform Jewish life and end special

institutions and customs. A belief existed that if the Jews

assimilated with the Poles, then they would prosper and would not be

persecuted. The Haskalah was popular among wealthy Jews, while the

shopkeepers and artisans chose to keep speaking Yiddish and continue

practicing Orthodox Judaism.

In the 19th century, the Haskalah

philosophy of integration began to be implemented by the Sejm

(Senate). The Jewish self-government, the Kahal, was abolished. A tax

was levied on Jewish liquor dealers, forcing them to close their

shops. Jews then became involved in agriculture. A yeshiva opened in

1826, with the goal of producing "enlightened" spiritual

leaders. In 1862, Jews were emancipated and special taxes were

abolished and restrictions on residence were removed. Despite efforts

to assimilate, Jews continued to be subject to anti-Semitism under

the Czars and in Poland.

Since Jews were treated badly by the Russians,

many decided to become in involved in the Polish insurrections: the

Kosciuszko Insurrection, November Insurrection (1830-1831), the

January Insurrection (1863) and the Revolutionary Movement of 1905.

Jews also joined Polish legions in the battle for independence

achieved in 1918.

In 1897, fourteen percent of Polish citizens were

Jewish. Jews were represented in government with seats in the Sejm,

municipals councils and in Jewish religious communities. Jews

developed many political parties and associations, ranging in

ideologies from Zionist to socialist

to Anti-Zionist. The Bund, a socialist party, spread throughout

Poland in the early 20th century. Many Jewish workers in Warsaw and Lodz joined the Bund.

Zionism also

became popular among Polish Jews, who formed the Poale Zion. Another

group, the Folksists (People’s Party) supported assimilation and

trade unions. The Polish Mizrahi, a Zionist orthodox political party,

had a large following. General

Zionists became popular in the inter-war period. In the 1919

election of the Sejm, the General Zionists received 50 percent of the

votes for Jewish parties.

After World War I

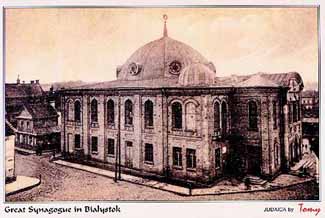

Synagogue in Bialystok

Synagogue in Bialystok |

In 1918, Poland became a sovereign state.

Following Poland’s rebirth, a reign of terror against the Jews

began. Jews were massacred in pogroms by Poles who associated Trotsky

and the Bolshevik revolution with Jewry (Trotsky was Jewish).

The situation was mixed for Polish Jews in the

inter-war period. They were recognized as a nationality and their

legal rights were supposed to be protected under the Treaty of

Versailles; however, their legal rights were not honored by Poland.

The Kehillah, a Jewish governing body, was not allowed to run

autonomously. The government intervened in the elections and

controlled its budget. On the other hand, Jews received funding from

the state for their schools.

Economic conditions declined for Polish Jews

during the inter-war years. Jews were not allowed to work in the

civil service, few were public school teachers, almost no Jews were

railroad workers and no Jews worked in state-controlled banks or

state-run monopolies (i.e. the tobacco industry). Legislation was

enacted forcing citizens to rest on Sunday, ruining Jewish commerce

that was closed on Saturday. Their economic downfall was accompanied

by a rise of anti-Semitism. In

the late 1930's a new wave of pogroms befell the community and

anti-Jewish boycotts were enacted.

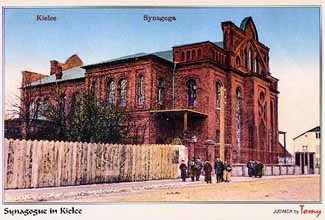

Synagogue in Kielce

Synagogue in Kielce |

Before the outbreak of World War II, there was a

thriving social and cultural life of Jews in Poland. A well-developed

Jewish press circulated newspapers in Polish, Hebrew and Yiddish.

There were more than 30 dailies and more than 130 Jewish periodicals.

More than fifty percent of all physicians and lawyers in private

practice in Poland were Jewish because of the discriminatory laws

against civil service. The Jewish population stood at 3.3 million,

the second largest Jewish community in the world.

The Holocaust

On September 1, 1939, Germany

invaded Poland. The German military killed about 20,000 Jews and

bombed approximately 50,000 Jewish-owned factories, workshops and

stores in more than 120 Jewish communities. Several hundred

synagogues were destroyed in the first two months of occupation.

Immediately, restrictions were placed on Polish

Jews. All Jewish stores were forced to display a Star

of David and were subsequently raided and forced to pay large

sums of money to the Germans. Jews were not allowed to own bank

accounts and there were limits on the amount of cash they could store

in their homes. Jews were not allowed in to work in textiles and

leather.

On July 24, 1939, instructions came from the High

Command of the Wehrmacht to intern civilian citizens, which led to

the arrest of Jews and Poles of military age at the time of the

invasion. Hundreds of civilians, Poles and Jews, were subsequently

murdered. Still more Polish Jews were killed by the Einsatzkommando.

One week before the invasion, Hitler signed a secret non-aggression pact (The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact)

with Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Under German occupation, Poland was

divided into 10 administrative districts. The western and northern

districts (Pomerania, Brandenburg, Saxony, Upper and Lower Silesia

and Danzig) were annexed to the German Reich and the eastern

districts were ceded to the Soviet Union. The largest district, the

central section including the cities of Lublin Krakow and Warsaw, was set

aside as a German colony and came to be known as the General

Government (Generalgouvernement).

When the German-Russian War began, the areas

previously controlled by Russia were incorporated into the Soviet

Union. Of the 3.3 million Polish Jews at the outbreak of the war,

about two million came under Nazi rule and the remainder were under

Soviet occupation.

Confinement

and Extermination

To provide more "living space" for

Germans, the Jews were removed from the Polish countryside and

concentrated in the cities of the General Government. The first ghetto was started as early as October 1939 in Piorków Trybunalksi and was

followed by the creation of ghettos in Lodz, Warsaw, Lublin,

Radom and Lvov. By 1942, all Polish Jews were either confined to

ghettos or hiding. That summer, the Nazis began liquidating the

ghettos and within 18 months almost all of them had been emptied.

Here is a brief description of what happened to the Jews in each

district:

- In Wartheland, there were nine ghettos,

the largest was the Lodz ghetto,

which was established in 1942. By the time the last transport left

the Lodz ghetto in August

1944, 74,000 Jews had been sent to Auschwitz.

The Soviets liberated the ghetto in January 1945 and found only 877

survivors.

- In Danzig-West Preussen, there was a

Jewish population of 23,000. Many Jewish residents were killed in

the initial massacres of the war. The last transport of Jews (about

2,000 people) were sent to Auschwitz on March 10, 1941.

- In Ciechanow, a census revealed about

80,000 Jews in 1931. Most of the Jews were expelled to Russia.

Those that stayed were sent to ghettos in East Prussia. The last

ghettos were liquidated in the fall of 1942 and the remaining Jews

were sent to Treblinka.

- In East Upper Silesia, there were 32

communities at the outbreak of the war, consisting of more than

93,000 Jews. From May to June 1942, Jewish workers from East Upper

Silesia were deported to Auschwitz.

- In the General Government, there were

four districts: Warsaw,

Lublin, Radome, and Cracow and the district of Galicia was added. More than 2.1 million Jews

resided in these districts before the occupation. The Nazis

established the Judenrat, a quasi-representative body of the Jews

in this district.

- In Warsaw,

the ghetto was established on November 15, 1940. More than half a

million Jews lived in the ghetto. About 300,000 Jews were deported

to Treblinka on September

1, 1942. In January 1943, the Nazis tried to start another round of

deportations, however, they were stopped after four days due to Jewish

resistance. On April 19, 1943, the German army entered the ghetto

and was met again by fierce opposition. It took several months, until

June 1943, before the ghetto was liquidated. The Warsaw

ghetto uprising reverberated throughout Poland and the rest of

the world as an example of courage and defiance.

- The first ghetto built in the district of Lublin,

in April 1941, held 45,000 Jews. Fifty forced labor camps were set

up in Lublin for local Jews as well as Jews from other districts.

In 1940-41, about 12,000 Jews occupied those camps.

- The district of Cracow had a pre-war Jewish population of 250,000. The first ghetto was established

in March 1941. The ghetto underwent three mass evacuations and, during

the final one, 2,000 Jews were murdered on the spot.

- In the district of Radome, eighty percent

of the Jewish population (360,000) lost their homes in the initial

bombings of the area. The others were deported into surrounding

areas. The first deportation to Treblinka occurred on August 5, 1942. On January 1, 1943, only 29,400 Jews

remained in the district’s four ghettos.

- In Galicia, the first ghetto was set up

in October 1941. On October 12, 10,000 Jews were killed at a Jewish

cemetery in the city of Stanislav.

- The district of Bialystok was created in July 1941 and contained a Jewish population of about

250,000 persons. Between June 27-July 13, 1941, more than 6,000 Jews

were murdered and the great synagogue was burned. In the final phase

of the extermination process, 40,000 Jews were killed and the rest

were sent to Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz.

Concentration

Camps

Poland had three major concentration

camps:

- Lublin-Majdanek

- Plaszow

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

Poland also housed six extermination camps:

- Auschwitz

- Majdanek

- Chelmno

- Treblinka

- Sobibor

- Belzec

Post-World War II & Communist Era

Eighty-five percent of Polish Jewry perished in

the Holocaust. Following the war,

many survivors fled to Romania and Germany in hope of reaching

Palestine. Those who remained attempted to rebuild Jewish life in the

200 local communities. The American Jewish Joint Distribution

Committee and ORT opened schools and hospitals for the Jewish

communities in Poland.

Jews were still subject to anti-Semitism and pogroms. The Kielce Pogrom in July 1946, in which 40 Jews were killed, was the impetus for

another mass emigration. At the end of 1947, only 100,000 Jews

remained in Poland.

The Soviet Union’s secret police essentially

governed the country and Stalin’s anti-Semitic regime stifled

Jewish cultural and religious activities. Jewish schools were

nationalized in 1948-49 and Yiddish was no longer used as the

language of instruction.

Stalin’s death in 1953 eased the situation for

the Jews, who then were allowed to reestablish connections with

Jewish organizations abroad and began producing Jewish literature. In

this 1958-59 period, 50,000 Jews emigrated to Israel, which was the

only country Jews were able to immigrate to under Polish law.

The last mass migration of Jews from Poland took

place in 1968-69, after Israel’s 1967

War, because of the anti-Jewish policy adopted by Polish

communist parties, which closed down Jewish youth camps, schools and

clubs. Following the 1967 War, Poland broke off diplomatic relations

with Israel.

In 1977, Poland began to try to improve its image

regarding Jewish matters. Partial diplmatic relations were restored

in 1986 — the first of the communistic block countries to take this

step — full diplomatic relations were not restored until 1990, a

year after Poland ended its communist rule.

Present Day Poland

Following the Holocaust when Jewish individuals who fled from Poland attempted to return to their homes and villages they faced a new wave of anti-Semitism and skepticism. Most of these people chose then to go on to Israel, America, or any other country that would have them. Approximately 20,000-25,000 Jews live in Poland today, mainly in Warsaw, but also in Cracow, Lodz, Breslau and other cities. Out of a total population of close to 40 million, the Jews represent at most .06%. Even though the Jewish population is so low and 90% of Polish individuals have never met a Jew according to the coordinator for the Center for Research on Prejudice in Warsaw, Poles still hold anti-Semitic attitudes. According to a 2013 survey 23% of Polish adults expressed traditional anti-Semitism, and this number represents a significant increase since 2009's statistic. The same 2013 survey showed than 60% of Polish adults harbor resentment of Jewish individuals and believe in a global Jewish conspiracy. Poland has yet to come to terms with what happened during the Holocaust, and remnants of that horrific time are still present on buildings and streetcorners. The outlines of the Warsaw Ghetto are still carved into sidewalks.

Jewish culture in Poland exists largely in the background today, with intermarriage being the norm and most Jewish individuals not practicing. Jewish culture and identity in Poland today are being carried on by individuals who are not necessarily Jewish. The Poland based Forum for Dialogue Among Nations operates in over 130 cities and towns around Poland, running programs that encourage high school students who may never meet a Jewish individual to explore the Jewish past of their country. The students research Jewish history of various towns and then make presentations to residents on walking tours. The Warsaw JCC is run by two women who both are skeptical about their Jewish roots but are deeply involved in the local Jewish community. Every Shabbat the Warsaw JCC welcomes over 50 non-Jewish volunteers who serve a free kosher meal to individuals in need.

Few Jews live in the eastern part of Poland, which at one time was home to large, important communities, such as those of Lublin and Bialystok. The Coordinating Committee of Jewish Organizations in the Polish

Republic (KKOZRP) coordinates the activities of the different Jewish

organizations in Poland. The Lauder Foundation has established a

number of clubs and events for Jewish youth as well as a primary school in Warsaw. The social and Cultural

Society of Jews in Poland helps with the renewal of Jewish life and

culture; it has branches in all major cities of Poland and publishes

the Folks-Syzme, a Yiddish and Polish weekly. The Union of

Religious Congregations, or Kehilla, has a main office in Warsaw and has branches in all cities with a sizeable Jewish population. The

Union maintains the Jewish cemeteries, synagogues and charities.

Kosher restaurants can be found in Warsaw and Cracow and the JDC

maintains Kosher cafeterias in the largest Jewish centers of Poland.

Synagogues can

be found in Warsaw, Cracow,

Zamosc, Tykocin, Lesko, Lanco, Rzeszow, Chmielnicki, Kielce and Gora

Kalwaria, but not all are functioning today. The oldest synagogue in

Poland, Stara Synagoga, built in the early 15th century,

can be found in Cracow. Today,

it hosts a Jewish museum. The Yeshiva Chachmei Lublin was reopened in Lublin in 2007, the first synagogue to be renovated and dedicated in Poland since World War II solely through funding from Polish Jewry, without government or charitable support. Prior to World War II, the yeshiva was Europe's largest.

The leading Jewish publications are the monthly Midrasz, Dos Jidische Wort, Jidele for youth and Sztendlach for primary school children. All of these publications are printed in Polish except for Dos Jidische Wort, which is published in a bi-lingual Yiddish-Polish edition. Jewish Institutions include the Jewish Historical Institute, the E.R. Kaminska State Yiddish Theater in Warsaw, and the Jewish Cultural Center in Cracow.

Chevra Lomdei

Mishnayot Synagogue, restored to its pre-war condition,

is the only synagogue in Oswiecim

to have survived World War II.

Chevra Lomdei

Mishnayot Synagogue, restored to its pre-war condition,

is the only synagogue in Oswiecim

to have survived World War II.

|

It

is also possible to visit the extermination camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek and Treblinka. Auschwitz currently houses the Oswiecim

State Museum, exhibiting documents from Nazi crimes. Block Number

27 is set aside for martyrology of the Jews and the millions who were

killed there.

All

that remains of Treblinka is a mausoluem and monument consisting of thousands of shards of

broken stone.

At Majdanek,

there is a museum and a monument, which incorporates a mound of human

ashes commemorating the 350,000 people who were murdered there.

Besides the camps, Poland also has the largest Jewish

burial ground in Europe, which is found in Lodz.

Historic grave sites can be found in Gora Kalwaria (the Ger) and Lesajsk

(Lezensk).

In June 2004, during an excavation of the site of the

Great Synagogue in Oswiecim, archeologists uncovered a unique collection

of Jewish treasures. Oswiecim's population was 70 percent Jewish, but

was wiped out after the German invasion of Poland. It is also where

the Auschwitz death camp

was built. In this project initiated by a young Israeli named Yariv Nornberg, archaeologists dug at the site based on the testimony of Holocaust survivor Yishayahu Yarod,

who remembered the relics being hidden by the Jews before the Nazis

razed the synagogue. Many Jewish ritual objects were found at the site,

including three bronze candelabras, a bronze menorah,

ten chandeliers and a ner tamid.

Tiles, marble plaques and charred wood from the synagogue were also discovered. The objects will most likely go through a year-long

restoration process and then be displayed in the Auschwitz Jewish Center.

On July 4, 2006, a memorial to Holocaust survivors killed

and wounded in Kielce,

Poland after World War II will was unveiled. The city of Kielce and

the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage

Abroad financed the memorial. On that day in 1946, residents killed

more than 40 Jews who had returned to the town after the war to reclaim

their property. The massacre consolidated the perception among survivors

that they couldn’t return to Poland.

Today there is greater awareness of Poland's rich Jewish past as well as of the tragedies of the Holocaust. Zaglada, a journal devoted to the Holocaust, was first published in 2005 by a special division of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Other publications have also been published recently dealing with the subject, most notably from the Institute of National Memory.

The Polish Jewish community is still receiving reparations from the Holocaust, however restitution is proceeding slowly. Legislation addressing the issue of private property has also yet to be enacted.

Public toilets built on the site of a Jewish cemetery in Szczelociny were finally removed in 2005 after urging from the World Jewish Congress and the Landsmanschaft. A memorial designed by the Polish-Jewish architect Czeslaw Bielecki, at the Radegest station, from which Lodz Jews were deported, was also unveiled in 2005.

In April 2013, the first part of the "Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews" in Warsaw - built on hallowed ground of the Warsaw Ghetto - opened to visitors interested in learning more about the Jewish community of the city. The museum itself is housed in a structure of green glass and stone, symbolic of transparency, and the main entrance faces a plaza dominated by the Nathan Rapoport memorial, which commemorates the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The museum's design was completed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma who were chosen from among 200 submissions to Poland’s first international architectural competition. The plot of land for the museum and an additional $13 million were donated by the city of Warsaw to the project.

Chief Curator of the Warsaw Museum and New York University Professor Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett said that the 1,000-year history of Polish Jews, 3 million of whom were killed during the Holocaust, was an “integral part” of the Poland’s history in general. “Jews are not a footnote to Polish history,” Kirshenblatt-Gimblett said.

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin joined Polish officials, Holocaust survivors, and media representatives on October 28 2014 for the final complete opening of Poland's new "Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews". The first part of the building was opened in April 2013 and the museum cost in total over $100 million. The museum was built on the grounds where the Warsaw Ghetto stood during the Holocaust. The visit to the opening of the museum was Israeli President Rivlin's first foreign trip since his election in Summer 2014. The core exhibit tells the story of the 1,000 year history of Jews in Poland through eight chronological gallery sections. The museum is meant to portray Polish Jewry in a positive light for the world, whose memories of the Holocaust are all to clear. Former Polish Ambassador to Israel Maciej Kozlowski said that "the Israelis are told that Poland is a dangerous place. They are seeing only Holocaust sites. This museum will change that."

Residents of the small Polish village Głowaczów dug up the graves in their town's Jewish cemetery during October 2015, supposedly looking for gold buried with the bodies.

The Israeli-made David's Sling missile defense system was included in a U.S.-Poland arms deal made public in September 2016. Raytheon, the U.S.-based company that manufactures the Patriot missile batteries used in the David's Sling system, offered the Polish military a version of the system in a deal worth an estimated $5 billion.

Poland's true test will come during the next decades, as they continue to pick up the pieces from communist rule and openly confront the Holocaust for the first time.

Sources: Beyond

the Pale: The History of Jews in Russia;

Gruber, Ruth Ellen. Jewish

Heritage Travel: A Guide to East-Central Europe. Jason Aronson,

Inc. Northvale, New Jersey, 1999;

"Newly Opened Museum Aims to Show Jews Not a 'Footnote to Polish History'," E-Jewish Philanthropy (April 17, 2013);

Johnson, Paul. A

History of the Jews. Harper & Row, Publishers. New York.

1987;

LNT

Poland;

March of

the Living - Canada;

Poland. Encyclopedia

Judaica. CD-ROM Edition. Judaica Multimedia. 1995;

Poland. Virtual Jerusalem - Jewish

Communities of the World;

Polish-Jewish

Relations;

Jerusalem Report, (July 26, 2004), p. 44; Jewish Records

Indexing – Poland;

Jewish Telegraphic Agency, (July 3, 2006);

The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary

Anti-Semitism and Racism, Annual Report 2005, Poland;

Wisse, Ruth. Jews and Power. Nextbook, Shocken: New York, 2007;

“Israeli and Polish presidents open Poland's Jewish museum,” Haaretz (October 28 2014);

Etzion, Udi.

“Israeli missiles to be included in US air defense deal to Poland,” YNet News (September 9, 2016)

Photo Credits: Stephen Epstein/Big

Dipper Communications; Shoah

- The Holocaust; ShtetLinks

Site for Lodz; The

Polish Jews; Scrap Book

Pages; Synagogue postcards courtesy of Tomasz

Wisniewski from the Synagogues

in Poland site and his Turn-of-the-century

postcards site; Auschwitz/Oswiecim photos courtesy of the Auschwitz

Jewish Center Foundation.

|