Beauty is in the Hands of its Creators: The Beauty of Books

More even than in the eye of the beholder, beauty lies in the hands of its creators. From the inception of printing creative artists labored to enhance the visual beauty of the book. Few if any subsequent printed books have surpassed the beauty of the first, the Gutenberg Bible. For Hebrew books the process began later and developed more slowly For sacred books in the sacred tongue, excepting only the Haggadah, the beauty favored was the beauty of the word, and almost all Hebrew books in the first three centuries of printing remained in that category. Nevertheless, there was a continuing impulse towards beauty in typography, decoration, and even illustration. Most often, such embellishments were limited to the title page, but not always.

|

Artistic bindings adorn many Hebrew books, and we choose one for its artistry as well as for its historic interest. In 1907, Israel Fine of Baltimore published Nginash Ben-Jehudah, a Selection of Poems and Memorials in Hebrew with partial translation into English. A poem in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt's birthday opens the volume. In the Library's Hebraic Section is a presentation volume bound in leather; inside, in fine cloth and appropriate colors, the flag of the United States appears on one cover, and an American seal and shield on the other. Someone has cut out the name of the recipient which was printed on the cover, but there is little doubt that it must have been President Roosevelt, for the author states that three years earlier, on October 24, 1904, he headed a delegation of prominent Baltimoreans, who called on the president and presented him with a poem "in the Hebrew language ... composed by Mr. Israel Fine and translated into English by his son, Mr. Louis Fine, hand-written on parchment in scroll shape and covered with a silk American flag."

|

A number of early Hebrew books were printed entirely on vellum to better preserve them and make them more attractive. Among these is Siddur Teflllah(Order of Prayer) According to the Rite of Rome, published in 1557 by Jacob ben Naphtali Ha-Kohen and "edited and arranged as a set table with all beauty by the scribe Meir ben Ephraim Sofer of Padua."

|

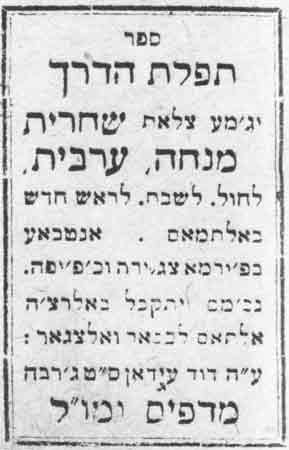

For aesthetic reasons books were printed on colored paper, A volume of the Mantua edition of the Zohar was printed on blue paper, quite common in early nineteenth-century Russia, but very rare in sixteenth-century Italy. More unusual still is a miniature 6 1/2 by 5 cm. (2 1/2 by 2 inch) Tefilat ha-Derekh (Prayers for a Journey) published on the Isle of Djerba in 1917 on rose-red paper. Books were also printed in colored type. An unusual example is Talpiot, a book of prayers by Elijah Gutmacher, published in 1882 in Jerusalem by Hayyim Hirschenson. The title page is indited in two shades of gold, and the text of the prayer is in gold throughout.

|

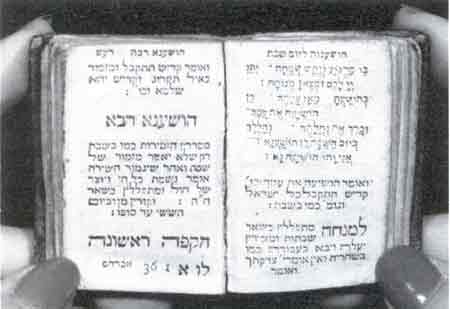

Many Hebrew books, especially prayer books and psalters, were in miniature editions so they could easily be carried in a pocket for daily devotions and for reciting the psalms while on a journey. The Library's Hebraic Section has a fine collection of such miniatures, among them, in a contemporary leather binding with matching box, a Seder Tefilot L'Moadim Tovim (Order of Prayer for the Holidays), Amsterdam, 1739, 4 by 6 cm. (1 5/8 by 2 2/8 inches).

|

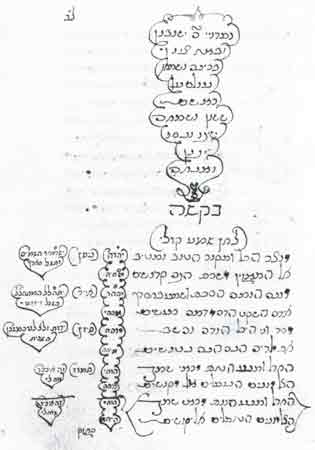

A gifted craftsman will often produce an artistic creation without conscious intention. Thus, a scribe in eighteenth-century Italy writing a Tikkun Hazot (Order of Service for Midnight Devotions), by Moses Zacut, produced pages of remarkable calligraphic and compositional artistry. A move conscious attempt to ad, beauty to the printed book comes in the artistic frame of lion, ox head, angels, and decorative branches which fills the margins of the first page of Sefer Shorashim, Book of Roots, published in 1491 by Joshua Soncino in Naples. The Soncino family worked consciously at quality book production. The title page of the 1526 Rimini edition of Sefer Kol Bo, printed by Gershom Soncino, not only has a stylized border, but features a very large representation of the Soncino logo — a tower, surrounded by the biblical verses: "The name of the Lord is a tower of strength, the righteous man runs into it and is safe" (Proverbs, 18: 10); and "In him my heart trusts and I am helped; And my heart exults and with song I will give thanks to him" (Psalms, 28:7).

|

A very beautiful title page was produced by the French artist and engraver Bernard Picart for the Tikkun Soferim Pentateuch, Amsterdam, 1726. At its top is the crown of Torah sustained by two putti angels; two other angels beneath hold an unfurled Torah scroll. Three cartouches surround the Hebrew title and the names of the three publishers — Samuel Rodriges Mendes, Moses Zarfati De Gerona, and David Gomez Da Silva. Each cartouche has an engraved biblical scene depicting an event in the lives of the biblical namesakes of the publishers. Under a royal crown, David meets Jonathan with the descriptive biblical verse: "The life of my lord shall be bound up in the bonds of life" (Samuel 1, 25:29). Under the crown of priesthood are Hannah and her infant son, Samuel, "And she called his name Samuel, for 'I asked him of the Lord"' (Samuel 1, 1:20). In the third cartouche, the baby Moses is brought before the Pharoah's daughter, "And she called his name Moses, because I have drawn him out of the waters" (Exodus, 2: 10).

|

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).