|

The history

of Spanish

Jewry dates back at least two thousand

years to when the Romans destroyed

the Second

Temple in Jerusalem,

and brought Jews with them back to Europe.

Since that time, the Jews of Spain (also known as Sephardim)

have experienced times of great oppression

and hardship, as well as periods of unprecedented

growth and renewal. Today the Jewish community in Spain is small - numbering approximately 12,000 - but growing, and the Jewish contributions to the nation and their influence on culture is still very much alive.

- Early History (205 BCE-711 CE)

- Muslim Rule (8-11th Century)

- Early Christian Rule (11-14th Century)

- Conditions Worsen (1369-1492)

- Inquisition & Expulsion

- Modern Community (1869-Present)

Early History (250 BCE - 711 CE)

While the area

of modern-day Spain (formerly

a collection of kingdoms which included Castile,

Aragon, and Catalonia) was still controlled

by the Holy Roman Empire, the Catholic Church

convened at the Council of Elvira where they

issued 80 canonic decisions, many of which

were intended to ostracize the Jews from

the general Spanish community. Canon 49, for example, prohibited Jews from blessing

their crops, and Canon 50 refused communion

to any cleric or layperson that ate with

a Jew.

During the early

5th century, the Visigoths captured

the Iberian Peninsula from Roman rule. While

initially anti-Christian, the Visigoths later

converted to Christianity and adopted many

of the previous laws that existed during Roman rule.

Under the rein of Toledo III, children of

mixed marriages were forcibly baptized and

Jews were barred from holding public office.

The situation got progressively worse and,

in 613 CE, the Jews were ordered to convert

to Christianity or face expulsion. Though

many Jews chose to leave rather than convert,

a large number of them still practiced Judaism in

secret, a tradition that survivedfor centuries.

In 633, the Fourth

Council of Toledo, convened to address

the problem of crypto-Judaism and Marranos (Jews who converted

to Christianity to escape persecution, yet

observed Jewish law in private).

While opposing compulsory baptism, the Council

decided that if a professed Christian was

determined to be a practicing Jew, his or

her children were to be taken away and raised

in monasteries or trusted Christian households.

Muslim Rule (8th - 11th Century)

In the 8th century,

the Berber Muslims (Moors) swiftly conquered

nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula. Under Muslim rule, Spain flourished,

and Jews and Christians were granted the

protected status of dhimmi.

Though this still did not afford them equal

rights with Muslims,

during this “Golden Age” of Spain,

Jews rose to great prominence in society, business,

and government.

The conditions

in Spain improved

so much under Muslim rule

that Jews from all across Europe came to

live in Spain during

this Jewish renaissance. There they

flourished in business and in the fields

of astronomy, philosophy, math, science,

medicine, and religious study. The same period

also witnessed a resurgence of Hebrew poetry

and literature from a traditional and liturgical

language to a living language able to be

used to describe everyday life. Among the

early Hebraists of the time were Yehudah

HaLevi who became known as one of the

first great Hebrew poets, and Menahem ben

Saruq who compiled the first ever Hebrew

dictionary.

The intellectual

achievements of the Sephardim (Spanish

Jews) enriched the lives of non-Jews as well.

In addition to contributions of original

work, the Sephardim translated

Greek and Arabic texts, which proved instrumental

in bringing the fields of science and philosophy,

much of the basis of Renaissance learning,

to the rest of Europe.

In the early

11th century, centralized authority based

at Cordoba broke

down following the Berber invasion and the

ousting of the Umayyads.

Rather than having a stifling effect, the

disintegration of the caliphate expanded

the opportunities to Jewish and other professionals.

The services of Jewish scientists, doctors,

traders, poets, and scholars were generally

valued by the Christian as well as Muslim rulers

of regional centers, especially as recently

conquered towns were put back in order.

Yet, despite

the Jews’ success and prosperity under Muslim

rule, the Golden Age of Spain began

to decline as the Muslims began to battle

the Christians for control of the Iberian

Peninsula and Spanish kingdoms in 722. The

decline of Muslim authority was matched with

a rise in anti-Semitic activity.

In 1066, a Muslim mob

stormed the royal palace in Granada,

crucified Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela

and massacred most of the Jewish population

of the city. Accounts of the Granada Massacre

state that more than 1,500 Jewish families,

numbering 4,000 persons, were murdered in

just one day. The conditions of Jews living on the

Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal)

steadily began to worsen again. As a result,

many people started fleeing the Iberian Peninsula

to neighboring nations. Among those who fled

were the famed bible commentators Abraham

Ibn Ezra and Rabbi

Yosef Karo (author of the Shulchan Aruch),

as well as the families of Maimonides and

philosopher Baruch

Spinoza. (Christopher Columbus is also

suspected by many to have been a Marrano,

though there exists no conclusive evidence

to substantiate this claim.)

The centuries-long battle between Christians and Muslims,

(known as the Reconquista), divided

neighboring regions in the Iberian Peninsula

until the Christians finally took full control

of the entire peninsula in 1492. Though initially

as hostile to the Jewish population as the Muslim rulers

had become, the Christians soon realized

that the Jews could prove a strong ally and

enlisted many of them in their war effort.

The Christians relied on the Jews for assistance

in fighting the Muslim rulers since the Jews

were familiar with the local language and

customs. Collaboration between the Jews and

Christians brought the Jews increased persecution

from Muslim rulers, but full autonomy in

Christian controlled regions.

Early Christian Rule (11th - 14th Century)

The

early years of Christian rule over parts

of Spain seemed

quite promising for the Spanish

Jews. Alfonso VI, the conqueror of

Toledo (1085), was tolerant and benevolent

in his attitude toward them, for which

he won the praise of Pope Alexander

II. Soon after coming to power, Alfonso

VI offered the Jews full equality with

Christians and even the rights offered

to the nobility to estrange the wealthy

and industrious Jews from the Moors. Jews prospered under Alfonso and by 1098, nearly 15,000 Jews were living in Toledo, a city of 50,000.

To

show their gratitude to the king for the

rights granted them, the Jews willingly

placed themselves at his and the country’s

service. At one point, Alfonso’s army contained

40,000 Jews, who were distinguished from

the other combatants by their black-and-yellow

turbans. (So honored and important were

the Jews to the Spanish army that the Spanish

chose not to initiate the battle of Zallaka

until after the Sabbath had

passed). The king’s favoritism toward the

Jews became so pronounced that Pope Gregory

VII warned him not to permit Jews to rule

over Christians and roused the hatred and

envy of the latter.

After

the Christian loss at the Battle of Ucles

(1108), an anti-Semitic riot

broke out in Toledo; many Jews were slain,

and their houses and synagogues burned.

Alfonso intended to punish the murderers

and incendiaries, but died before he could

carry out his intention (1109). After his

death the inhabitants of Carrion slaughtered

the local Jews, others were imprisoned

and their houses pillaged.

In

the beginning of his reign, Alfonso VII

(1111) curtailed the rights and liberties

that his father granted the Jews. He ordered

that neither a Jew nor a convert may exercise

legal authority over Christians, and he

held the Jews responsible for the collection

of the royal taxes. Soon, however, he became

friendlier, confirming the Jews in all

their former privileges and even granting

them additional ones, by which they were

placed in parity with Christians. Judah

ben Joseph ibn Ezra had considerable influence

with the king, and after the conquest of

Calatrava (1147), the king placed Judah

in command of one of his fortresses, later

making him his court chamberlain.

Under

the reign of Alfonso VIII, the Jews gained

still greater influence, aided, doubtless,

by the king’s love of the beautiful Jewess

Rachel Fermosa of Toledo. When the king

was defeated at the battle of Alarcos,

many attributed the defeat to the king’s

love affair with Fermosa, and the nobility

retaliated by murdering her and her relatives

in Toledo.

Despite

the reclaimed status of the Jews

in Spain, their condition soon began

to worsen once again as the Crusaders unleashed

another round of anti-Semitic riots

in Toledo (1212), robbing and butchering

Jews across the nation. During the 13th century, Spanish

Jews of both sexes, like the Jews of France,

were required to distinguish themselves

from Christians by wearing a yellow badge

on their clothing; this order was issued

to keep them from associating with Christians,

although the reason given was that it was

ordered for their own safety.

During

this time, the clergy’s endeavors directed

against the Jews became increasingly pronounced

as well. A papal bull issued by Pope Innocent

IV in April 1250 further worsened the

situation of the Jews

in Spain by

prohibiting Jews from building new synagogues without

special permission, outlawing proselytizing

by pain of death, and forbidding most forms

of contact between Jews and Christians.

According to the decree, Jews were also

forbidden to appear in public on Good Friday.

The Jews of Spain were

also forced to live as a separate political

body in the Juderias (Jewish ghettos).

Nachmanadies (Ramban)

Nachmanadies (Ramban) |

Although

the Spanish

Jews engaged in many branches of human

endeavor—agriculture, viticulture,

industry, commerce, and the various handicrafts—it

was the money business that procured them

their wealth and influence. Kings and prelates,

noblemen and farmers, all needed money,

and could obtain it only from the Jews,

who were forced to act as bailiffs, tax-farmers,

or tax-collectors since Christians were

forbidden from charging each other interest

rates. Becuase of their acquired wealth,

as well as government anti-Semitism,

Jews were also forced to pay many additional

and exorbitant taxes to the king.

Disputation

of Barcelona

Though

their holy texts were often burned by royal

decree, and many Jews were forced to convert

to Christianity, during the rule of King

James of Aragon (a Christian-ruled province

of Spain)

the Spanish monarchy started to take an

interest in Jewish philosophy and religion,

if only so that they could better understand

Jews and convince them to convert. In 1263,

King James convened a special council of

Dominican (Christian) and Jewish clergymen

to debate three key theological issues:

whether the Messiah had

already appeared, whether the Messiah was

divine or human, and which religion was

the true faith. Nachmanides (Rabbi

Moshe ben Nahman Gerondi, Ramban),

a Jewish theologian and philosopher was

called upon to represent the Jews; while

Friar Pablo Christiani, a Jew who later

converted to Christianity, represented

the Church.

The

disputation lasted four days and drew the

attention of the entire Jewish community.

Though the King granted Nachmanides the

freedom to speak freely, the Jewish community

feared that any statement that offended

the King would lead to increased persecution.

As the disputation turned in favor of Nachmanides the

Jews of Barcelona entreated

him to discontinue; but the King, whom Nachmanides had

acquainted with the apprehensions of the

Jews, desired him to proceed. At the end

of disputation, King James awarded Nachmanides a

prize and declared that never before had

he heard “an unjust cause so nobly

defended.” Despite the King’s declaration,

the Dominicans still claimed victory, which

led Nachmanides to

publish a transcript of the debate to prove

his case. From this publication, Christiani

selected certain passages which he construed

as blasphemies against Christianity and

denounced to his general Raymond de Penyafort.

A capital charge was then instituted, and

a formal complaint against the work and

its author was lodged with the King. King

James mistrusted the Dominican court and

called an extraordinary commission, ordering

the proceedings to be conducted in his

presence. Nachmanides admitted

that he had stated many things against

Christianity, but he had written nothing

which he had not used in his disputation

in the presence of the King, who had granted

him freedom of speech.

The

justice of his defense was recognized by

the King and the commission, but to satisfy

the Dominicans, Nachmanides was

sentenced to exile for two years and his

pamphlet was condemned to be burned. The

Dominicans, however, found this punishment

too mild and, through Pope Clement IV,

they succeeded in turning the two years

exile into perpetual banishment. Nachmanides left

Aragon never to return again and, in 1267,

he settled in the Land

of Israel. There he founded the oldest

active synagogue in

the Old City of Jerusalem,

the Ramban Synagogue.

The Reign of Pedro I

During

the reign of Pedro I (1350-1369), the quality

of Jewish life in Spain began

to improve and the King became a well-known

friend to the Jews. From the commencement

of his reign, Pedro so surrounded himself

with Jews that his enemies spoke derisively

of his royal court as “a Jewish court.” In 1357, Samuel Levi financed the construction of the Sinagoga del Transito, which served as the center of Todelo's Jewish life. It is also believed that during this time kosher slaughterhouses and butchershops sprang up along the main streets of Toledo.

Soon,

however a civil war erupted and a rival

army, led by Pedro I’s half brother

Henry II, attacked the Jews. During the

war, part of the Juderia of Toledo was

plundered and about 12,000 Jews were murdered

without distinction of age or sex. The

mob did not, however, succeed in overrunning

the Juderia proper, where the Jews, reinforced

by a number of Toledan noblemen, defended

themselves bravely.

The

friendlier Pedro was to the Jews and the

more he protected them, the more antagonistic

his half brother became. Later, when Henry

II invaded Castile in 1360, he robbed and

butchered the Jews living in Miranda de

Ebro and Najera.

Yet,

everywhere the Jews still remained loyal

to Pedro and fought bravely in his army.

In return, Pedro I showed his good will

toward them, and called upon the King of Granada to

also protect the Jews. Nevertheless, the

Jews suffered greatly. Villadiego (whose

Jewish community numbered many scholars),

Aguilar, and many other towns were destroyed.

The inhabitants of Valladolid, who paid

homage to Henry, robbed the Jews, destroyed

their houses and synagogues,

and tore their Torah scrolls.

Paredes, Palencia, and several other communities

met with a similar fate, and 300 Jewish

families from Jaen were taken prisoners

to Granada.

Pedro was eventually defeated and succeeded

by Henry de Trastamara.

Conditions Worsen (1369 - 1492)

When

Henry de Trastamara ascended the throne

as Henry II (1369), the Jews

of Spain witnessed

the dawn of a new era of suffering and

persecution. Prolonged warfare devastated

the land, and the people became accustomed

to lawlessness. The Jews were reduced to

extreme poverty and later expelled.

In

addition, Henry II decreed that Jews:

1)

Be kept far from palaces;

2)

Were forbidden to hold public office;

3)

Must live separate from Christians;

4)

Should not wear costly garments nor ride

on mules;

5)

Must wear distinct badges to indicate that

they were Jewish;

6)

Were barred from adapting Christian names;

7)

Were forbidden to carry arms and sell weapons.

Despite

his aversion for the Jews, Henry could

not dispense with their services. He employed

wealthy Jews—Samuel Abravanel and

others—as financial councilors and

tax collectors. He also did not prevent

them from holding religious disputations

or deny them the right to conduct their

own court proceedings.

Massacre of 1391

Under the rule of

John I (1379-1390), things grew even worse

for the Jewish community of Spain.

Jewish courts were forbidden from calling

for capital punishment, Jews were forced

to change prayers deemed offensive to the

Church, and people were forbidden to convert

to Judaism on

pain of becoming property of the State. Anti-Semitic violence

also increased during this period, and

Jews were often beaten or even killed

in the streets.

A

revolt broke out in Seville after

the death of King John I in 1390, leading

to a period of disorder which greatly affected

the Jewish

community of Spain in the coming years.

On Ash Wednesday 1391, Ferrand Martinez,

the Archdeacon of Ecija, urged Christians

to kill or baptize the Jews

of Spain. On June 6, the mob attacked

the Juderia in Seville from

all sides and murdered 4,000 Jews; the

rest submitted to baptism as the only means

of escaping death. The riots then spread

across the countryside destroying many synagogues and

murdering thousands of Jews in the streets.

During the months-long riots, the Cordova

Juderia was burned down and over 5,000

Jews ruthlessly murdered regardless of

age or sex. Again, more Jews converted

as the only way to escape death.

Soon

after, a series of laws were passed to

reduce the Jews to poverty and further

humiliate them. Under these laws, the Jews

were ordered to:

1)

Live by themselves in enclosed Juderias;

2)

Banned from practicing medicine, surgery,

or chemistry;

3)

Banned from selling commodities such as

bread, wine, flour, meat, etc.;

4)

Banned from engaging in handicrafts or

trades of any kind;

5)

Forbidden to hire Christian servants, farm

hands, lamplighters, or gravediggers;

6)

Banned from eating drinking, bathing, holding

intimate conversation with, visiting, or

giving presents to Christians;

7)

Banned from holding public offices or acting

as money-brokers or agents;

8)

Christian women, married or unmarried,

were forbidden to enter the Juderia either

by day or by night;

9)

Allowed no self-jurisdiction whatever,

nor might they, without royal permission,

levy taxes for communal purposes;

10)

Forbidden to assume the title of “Don”;

11)

Forbidden to carry arms;

12)

Forbidden to trim beard or hair;

13)

Jewesses were required to wear plain, long

garments of coarse material reaching to

the feet, and Jews were forbidden to wear

garments made of fine material;

14)

On pain of loss of property and even of

slavery, Jews were forbidden to leave the

country, and any grandee or knight who

protected or sheltered a fugitive Jew was

punished with a fine of 150,000 maravedís

for the first offense.

These

laws were strictly enforced, and calculated

to compel the Jews to embrace Christianity.

Though

these laws were targeted against the Jews,

with them suffered the entire kingdom of Spain.

Commerce and industry were at a standstill,

the soil was left uncultivated, and the

finances disturbed. In Aragon entire communities—as

those of Barcelona, Lerida, and Valencia—were

destroyed, and many had lost more than

half of their members and were reduced

to poverty.

After

the persecutions of 1391, many Jews converted,

and still thousands more continued to practice Judaism in

secret (these people were known as Marranos).

On account of their talent and wealth,

and through intermarriage with noble families,

the converts and Marranos gained

considerable influence and filled important

government offices. To restore commerce

and industry, Queen Maria, consort of Alfonso

V and temporary regent, endeavored to draw

Jews to the country by offering them rights

and privileges while making emigration

difficult by imposing higher taxes.

Inquisition & Expulsion

Sketch

depicting one of the brutal torture methods

used to interogate Marranos into

confessing that they were Jewish

during the Spanish Inquisition

Sketch

depicting one of the brutal torture methods

used to interogate Marranos into

confessing that they were Jewish

during the Spanish Inquisition |

By

the mid-15th century, hatred toward the

Neo-Christians exceeded that toward the

professed Jews. Later, in 1413, at

the behest of Pope Benedict

XIII, King Ferdinand I of Aragon called

for another religious disputation similar

to that held two centuries earlier. Yet,

unlike the disputation in which Nachmanides succesfully

defended the Jews

of Spain, the Disputation of Tortosa

was structured in such a way that it always

granted the final word to the Church. The

King also was not as favorable to the Jews,

and the representatives of the Jewish community

less eloquent and convincing than Nachmanides had

been. Jews were subsequently forcibly converted

and rabbinic texts were confiscated and

burned.

The

nobles of Spain later

found that they had only increased their

difficulties by urging the conversion of

the Jews, who remained as devout in

their new faith as they had been in the

old, and gradually began to monopolize

many of the offices of state, especially

those connected with tax-farming. In 1465,

a “concordia” was imposed upon

Henry IV of Castile, reviving all the former

anti-Jewish regulations. (So threatening

did the prospects of the Jews become that

in 1473 they offered to buy Gibraltar from

the king; the offer was refused.)

As

soon as the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand

and Isabella ascended their thrones (1479

and 1474, respectively), steps were taken

to segregate the Jews both from the “conversos” and

from their fellow countrymen. Though both

monarchs were surrounded by Neo-Christians,

such as Pedro de Caballeria and Luis de

Santangel, and though Ferdinand was the

grandson of a Jew, he showed the greatest

intolerance to Jews, whether converted

or otherwise.

Anti-Semitism in Spain peaked

during the rule of Ferdinand and Isabella

as they instituted the Spanish

Inquisition, a Church sponsored investigation

of anyone suspected of being a crypto-Jew

(Marrano).

On November 1, 1478, Pope Sixtus

IV published the bull Exigit Sinceras

Devotionis Affectus, through which

the Inquisition was

established in the Kingdom of Castile.

During this period, thousands of Marranos (Jews

who had converted to Christianity but still

practiced Judaism in secret) were interrogated

and executed. At first, the activity of

the Inquisition was

limited to the dioceses of Seville and Cordoba,

where Alonso de Hojeda had detected the

center of Marrano activity.

From there, the Inquisition grew

rapidly in the Kingdom of Castile. By 1492,

tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities: Ávila, Córdoba,

Jaén, Medina del Campo, Segovia,

Sigüenza, Toledo and Valladolid. The

first auto de fe (reading of a

decree against someone found to be a heretic,

followed by a prayer session and public

procession) was celebrated in Seville on

February 6, 1481 — six people were burned

alive.

Despite

the horrors of the Inquisition,

the cities of Aragón continued resisting,

and even saw periods of revolt, such as

in Teruel from 1484 to 1485. However, the

murder of inquisidor Pedro Arbués

in Zaragoza on September 15, 1485, caused

public opinion to turn against the Marranos in favor of the Inquisition.

The Inquisition was

extremely active between 1480 and 1530,

during which time about 2,000 Jews were

executed. Many Spanish

Jews immigrated to Portugal (from

where they were expelled in 1497) and to Morocco.

Much later the Sephardim,

descendants of Spanish

Jews, established flourishing communities

in many cities of Europe, North Africa,

and the Ottoman

Empire.

The

Al Hambra Decree signed in 1492 by King

Ferdinand and Queen Isabella ordering the expulsion of

the Jews from all land under their control.

The

Al Hambra Decree signed in 1492 by King

Ferdinand and Queen Isabella ordering the expulsion of

the Jews from all land under their control. |

Approximately

40,000 Jews converted to Christianity to

escape death and expulsion. These conversos were

the principal concern of the Inquisition;

continuing to practice Judaism put

them at risk of denunciation and trial.

(During the 18th century the number of conversos accused

by the Inquisition decreased

significantly. Manuel Santiago Vivar, who

was tried in Cordoba in

1818, was the last person tried for being

a crypto-Jew.)

Expulsion of 1492

Finally,

Ferdinand and Isabella issued the Alhambra

Decree in 1492, which officialy called

for all Jews, regardless of age, to leave

the kingdom by the last day of July (one

day before Tisha

B’Av). It is estimated that more than

235,000 Jews lived in Spain before

the inquisition. Of these, approximately

165,000 immigrated to neighboring countries

(mostly to Italy, England, Holland, Morroco, Egypt, France,

and the Americas), 50,000 converted to

Christianity, and 20,000 died en route

to a new location.

Some

claim that Don

Isaac Abravanel, who had previously

ransomed 480 Jewish Moriscos of Malaga

from the Catholic monarchs by a payment

of 20,000 doubloons, offered Ferdinand

and Isabella 600,000 crowns for the revocation

of the edict of expulsion. As the story

goes, Ferdinand hesitated, but was prevented

from accepting the offer by Torquemada,

the grand inquisitor, who dashed into the

royal presence, threw a crucifix down before

the king and queen, and asked whether,

like Judas, they would betray their Lord

for money.

Many Spanish

Jews settled in Portugal,

which allowed the practice of Judaism.

In 1497, however, Portugal also

expelled its Jews. King Manuel of Portugal agreed

to marry the daughter of Spain’s

monarchs. One of the conditions for the

marriage was the expulsion of Portugal’s

Jewish community. In actuality, only eight

Jews were exiled from Portugal and

the rest converted, under duress, to

Christianity.

The Alhambra

Decree was overturned in 1968.

Modern Community (1869 - Present)

After

hundreds of years abroad, Jews were finally

permitted to return to Spain after the abolition of the Inquisition in 1834 and the creation of a new constitutional monarchy that allowed for the practice of faiths other than Catholicism in 1868, though the edict of expulsion

was not repealed until 1968. (From 1868

until 1968, Jews were allowed to live in Spain as

individuals, but not to practice Judaism as

a community.) The Spanish Moroccan War of 1859-60 also brought many Jews to southern Spain who were fleeing Morocco. Small numbers of Jews started

to arrive in Spain in

the 19th century, and synagogues were

eventually opened in Madrid and Barcelona.

Slowly things began to improve and Spanish

historians even started to take an interest

in the history of Spain’s

Jewish population and in the Sephardic

language of Ladino (Judeo-Spanish).

The government of Miguel Primo de Rivera

(1923-1930) even granted the right of Spanish

citizenship to Sephardim who

applied before December 31, 1931.

In 1917, the Jews of Madrid numbers around 1,000 people. Most were German, Austrian-Hungarian and Turkish citizens who fled to Spain at the beginning of World War I. They inaugurated their first synagogue in a small apartment. The world economic crisis of 1929 brought additional Jews to the country.

During

this period, Jews slowly began to return

to Spain and

take part in national affairs. During the

Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), many Jews

from all over Europe and America volunteered

to fight in support of the Spanish Second

Republic. Despite the easing of tensions

between the Spanish government and the

Jews, synagogues in Spain remained

closed.

The Holocaust

During World

War II , Franco-led Spain aided

the Jews by permitting 25,600 Jews to

use the country as an escape route from

the European theater of war, provided

they “passed through leaving no

trace.” Paradoxically, though Spain later

cultivated relations with Arab countries,

it also assisted Moroccan and Egyptian Jews

who survived pogroms.

Furthermore,

Spanish diplomats such as Ángel

Sanz Briz and Giorgio

Perlasca protected some 4,000 Jews

in France and the Balkans. In 1944, Spain accepted 2,750 Jewish refugees from Hungary.

Later, as the Franco regime

evolved, synagogues were

opened and the communities were permitted

to hold services discreetly.

Contemporary Period

Today,

there are approximately 12,000 Jews living

in Spain,

mainly of North

African-Sephardic descent. The Jewish

community is led by the central governing

body of the Federación de Comunidades

Judías de España (FCJE).

Like other religious communities in Spain,

FCJE has established agreements with the

Spanish government, regulating the status

of Jewish clergy, places of worship, teaching,

marriages, holidays, tax benefits and heritage

conservation. Jewish day schools have also

been established in Barcelona,

Madrid, and Málaga. In the 1970s,

there was also an influx of Argentinian

Jews, mainly Ashkenazim,

escaping from the military Junta. Spain

also grows kosher olives which they export

to Jews around the world.

The Spanish Jewish community is one of the few Jewish communities in Western Europe that is growing in both numbers and activities. The Spanish government has made an increased effort to increase the awareness of the role that the Jews once played in Spanish life and to combat anti-Semitism.

Despite

interest in Jewish culture, Jews are still

not completely safe from anti-Semitism.

Many Spanish-Jewish leaders

note that the presence of the “new anti-Semitism” is

growing. This new form uses anti-Zionism as

a disguise for anti-Semitism. A 2007 survey by the Anti-Defamation League revealed that Spain had the highest percentage of anti-Semitic views out of five European countries polled: Austria, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland. Spain also has an estimated 70 neo-Nazi and anti-Semitic groups with nearly 10,000 members, according The Movement Against Intolerance. Additionally, in 2008, Spain’s constitutional court ruled that imprisonment for Holocaust denial is unconstitutional since it violates freedom of expression. Until this ruling, Spain’s criminal code had provided for one to two years in jail for anyone who disseminated theories or teachings that denied or justified genocide or other crimes against humanity. The new ruling makes only the justification of genocide punishable by prison. Jewish community leaders worry that the court’s decision will strengthen the activities of neo-Nazi groups.

The Jewish community is centered in Madrid with around 12,000 Jews. Barcelona also has a sizeable Jewish community of 5,000 members. In addition, Jewish congregations, including a handful of Conservative and Reform communities, can be found in cities such as Valencia, Malaga, and Marbella as well as the Spanish North African enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. In 2007, a modern Orthodox synagogue was established in the city of Alicante on the Costa Blanca, where about 1,000 Jews reside. There are also Jewish day schools in Madrid, Barcelona and Melilla.

The Conservative congregation in Madrid, Beit El, conducts weekly Shabbat services in a small hall in an apartment building. Beit El is one of five Conservative synagogues in Spain. These congregations are popular because many of Spains more recent immigrants follow the Ashkenazi tradition and do not observe the Sephardi traditions of the main Orthodox community. There is also an independent Reform congregation in Madrid but a large number of Jews remain unaffiliated.

In 1995, the Spanish goverment created the "Route of the Sephardim," a network of historical tours aimed to help reclaim the country's Jewish history while also generating tourism. The Route has grown to include 21 cities throughout the country.

In the small community that still exists in Toledo, a museum dedicated to the Sephardic Jewish community is now housed in the ancient Sinagoga del Transito. The synagogue itself has been restored to original beauty, which consisted of richly decorated columns in Arabic style with an exquisitely coffered pinewood ceiling and a large women's balcony, was founded in 1357 with the help of Jewish financier Samuel Levi. Following the expulsion in 1492, the synagogue was used as a hospital, a priory, and even as a military barracks.

In March 2013, the Spanish town of Ribadavia will host a Passover seder - the town's first since the explusion of Jews in 1492 - in order to "breathe new life into its old Jewish quarter." Ribadavia used to have a sizable Jewish population before the Inquisition, and in 1997, Judith Cohen, a scholar of Sephardic Jewry, wrote that Ribadavia had two Jewish households remaining, neither of them Sephardic. The seder is being organized by the municipality’s tourism department in partnership with the Center for Medieval Studies, a Ribadavia-based association that researches the history of Iberian Jews prior to their expulsion during the Spanish Inquisition that began in 1492.

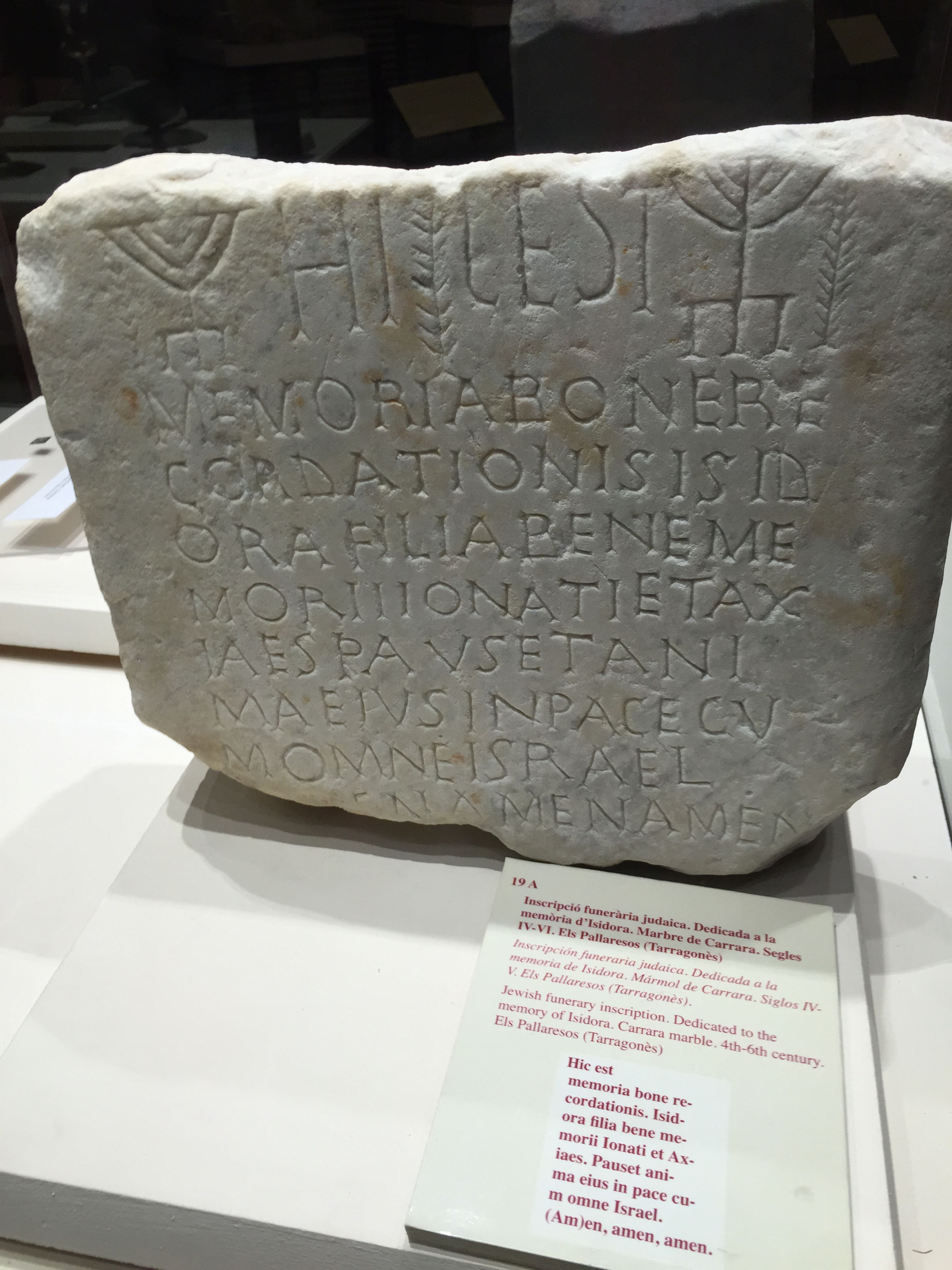

An inscribed tablet in the Barcelona Jewish Museum.

An inscribed tablet in the Barcelona Jewish Museum. |

The Spanish Parliament approved a measure on June 11, 2015, aimed at restoring citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jewish individuals who were expelled during the Inquisition. The law allows relatives of individuals who were expelled to apply for dual citizenship within a three-year window. In order to prove citizenship however, Sephardic Jewish applicants will be tested in basic Spanish speech, be questioned about the history of Spain, and will have to demonstrate a connection to modern Spain. This law is similar to the law passed previously in Portugal, allowing relatives of expelled Sephardic Jews the right of return. Three months later, in October 2015, Spain granted restored citizenship to 4,302 descendants of Sephardi Jews expelled from Spain during the Inquisition. These people are now fully naturalized citizens of Spain, and most of them currently reside in Morocco, Turkey, or Venezuela.

This noble plan to reconnect Sephardic Jews with their Spanish roots inspired Israel Foreign Ministry Advisor Ashley Perry to launch the Knesset Caucus for the Reconnection with the Descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish communities in October 2015.

On November 19, 2015, a Holocaust memorial in Oviedo, Spain was vandalized by unknown criminals. A plaque on the memorial, reading “Never again will the barbaric acts of the Nazis be repeated,” was ripped from it's place and stolen. The Jewish community appealed to their local government to restore the memorial to it's original condition.

Spain-Israel Relations

Even

with the gradual ease of tensions between

the Spanish government and the Jews

of Spain, Francoist Spain chose

not to establish diplomatic relations with

the new state of Israel. Israel,

in turn, opposed the admission of Spain into

the United

Nations as a friend of Nazi

Germany. Despite not engaging in diplomatic

relations with Israel, Spain maintained

a consulate in Jerusalem and

traded freely with Israel.

After years of negotiations, the Spanish

government of Felipe González established

relations with Israel in

1986. Today, Spain tries

to serve as a bridge between Israel and

the Arabs as reflected by hosting the Madrid

Peace Conference of 1991.

Casa Sefarad-Israel (The Israel-Spain House) was established in Madrid by the Spanish Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Ministry in June 2007. The cultural and educational center hopes to foster greater understanding of Jewish history and culture. It is completely financed by the Spanish government, and also promotes Sephardi culture as an integral and vibrant part of Spanish culture and aims to strenghten bonds between Spanish and Israeli societies.

On November 19 2014 members of Spain's Parliament voted 319-2 in favor of a measure demanding that the government of Spain officially recognizes the Palestinian state. This vote follows votes in British Parliament and the Irish Senate, as well as a pledge from the government of Sweden. Like all of these previous votes in other European countries in 2014, this vote is largely symbolic and in reality carries no weight or merrit. The vote was simply taken as a symbolic measure to encourage the peace process and spur negotiations forward. The text of the bill clarifies that the only possibility for peace is the existance of two independent states coexisting next to each other.

In light of these recent votes to recognize a Palestinian state, EU Foreign Policy Chief Federica Mogherini expressed doubts as to whether the movement to unilaterally recognize Palestine is beneficial to the peace process. Mogherini explained that "The recognition of the state and even the negotiations are not a goal in itself, the goal in itself is having a Palestinian state in place and having Israel living next to it." She encouraged European countries to become actively involved and push for a jump start to the peace process, instead of simply recognizing the state of Palestine. Mogherini said that the correct steps to finding resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict might involve Egypt, Jordan, and other Arab countries forming a regional initiative and putting their differences aside at the negotiation table. She warned her counterparts in the European Union about getting "trapped in the false illusion of us needing to take one side" and stated that the European Union "could not make a worse mistake" than pledging to recognize Palestine without a solid peace process in place. (Bloomberg, November 26 2014)

The Spanish Armed Forces awarded Israeli firm Israel Military Industries (IMI) a contract worth $22.5 million Euro to supply the Spanish military with 5.56mm rifle cartriges. It was announced in October 2015 that Spain would be purchasing 5.56mm Razor Core rounds from Israel, which were developed in 2014. These 5.56mm Razor Core bullets are highly desirable because they can be used in both short and long barrel weapons.

A Spanish judge issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu as well as six other current and former Israeli officials during November 2015. The original case against Israel's leaders, in which Spanish victims of the Gaza Flotilla Incident sued Israeli authorities, was dismissed in 2010 by a Spanish judge who ruled that Spain did not have the authority to file lawsuits regarding international incidents. In 2015 however, Spanish Judge Jose De La Mata exploited a legal loophole, allowing him to re-open the case if one of the defendants were to set foot in Spain.

Contacts

Orthodox Beth El synagogue

in Marbella:

Urbanizacion El Real, KM 184, Jazmines

Str. 21

Telephone: +34-952-859395

Fax: +34-952-765783

E-mail: [email protected]

The Beth Minzi synagogue

in Torremolinos:

Calle Skal la Roca 13 29629

Telephone: +34-95-383952

Fax: +34-95-2370444

The e-mail of the local Rabbi, Rabbi Shaul

Khalili, is: [email protected]

The Malaga Synagogue:

Alameda Principal, 47 20B 29001

Telephone: +34-95-260409

Sources: DW (November 19 2014);

Wikipedia;

WAIS-Stanford;

James Reston, Jr., Dogs

of God: Columbus, the Inquisition, and the

Defeat of the Moors, NY: Anchor,

2006;

Gazzar, Brenda, “Taking Root, Again,” The Jerusalem Report (September 29, 2008);

Hedy Weiss, "The Jewish Traveler: Sefardic Routes," Hadassah Magazine, (June/July 2012);

"Spanish Town Preparing First Seder in 500 Years," JTA (March 11, 2013);

Neuger, James. “Palestine recognition 'not goal in itself' says EU's Mogherini,” Bloomberg (November 26, 2014);

Lappin, Yaakov. “IMI to supply Spain with NATO-qualified ammunition,” Jerusalem Post (September 30, 2015);

Borschel, Amanda. “Knesset caucus aims to ‘reconnect’ with descendants of Sephardi Jews,” Times of Israel (October 14, 2015)

Photo Credits:Nachmanides Potrait: Zohar-Hakabbalah

Inquisition Drawing: Australian Ejournal of Theology

Al Hambra Decree: Wikipedia

|