When Churchill Severed Transjordan From Palestine

(1921)

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement envisioned the establishment of mandates for France (Lebanon and Syria) and Britain (Palestine and Iraq). As a reward for help in defeating the Ottomans, the son of Sharif Hussein of the Hashemite dynasty was installed by the British as the ruler of Syria. The French, however, expelled him in 1921 and the British made Faisal bin Hussein the king of Iraq the following year.

The Hashemites had earlier been expelled from the Hejaz, what is now Saudi Arabia, and the Saudis would fear for many years afterward they might try to return and expel the Wahhabis ruling the country.

According to Frank Jacobs, “Faisal bin Hussein was on his way to help his brother Abdullah in Syria when Winston Churchill implored him to renege, using the prospect of a crushing defeat by the French as stick, and the promise of Abdullah’s own dynasty as carrot.”

Winston Churchill said that “with the stroke of a pen one Sunday afternoon in Cairo” in 1921 he created the British mandate of Transjordan, now known as the Kingdom of Jordan. Apparently, having been drinking that day, the colonial secretary’s penmanship was wobbly, “allegedly producing a particularly erratic borderline.” The resulting zigzag that delineates the border between Jordan and Saudi Arabia is sometimes referred to as “Winston’s Hiccup” or “Churchill’s Sneeze.”

“The British,” Jacobs notes, “saw Transjordan’s value mainly as a transit zone between Palestine and Iraq, but also as part of an air corridor (back when flights were relatively short and refuelings many) between Britain and India.” The location of the Eastern border between Transjordan and Iraq was also considered strategic with respect to the proposed construction of what became the Kirkuk–Haifa oil pipeline.

Transjordan, so-called because of its position on the east side of the Jordan River, was originally part of the British Mandate for Palestine created at the San Remo Conference in 1920. That mandate had recognized the Balfour Declaration, which envisioned that a Jewish national home would be created in all of Palestine.

A memo regarding Transjordan written on March 12, 1921, prior to the convening of the Middle East Conference held in Cairo, explains the British decision to alter the original mandate:

On March 12, 1921, Churchill telegrammed the Colonial Office (paraphrased):

The Colonial Office responded (paraphrased):

-

(To be inserted after article 15 of the Mesopotamian mandate):

“Nothing in this mandate shall prevent the mandatory from establishing such an autonomous region system of administration for the predominantly Kurdish areas in the northern portion of Mesopotamia as he may consider suitable.”

- (To be inserted after article 24 of the Palestine mandate):

“In in the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the mandatory shall be entitled to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those conditions, provided no action shall be taken which is inconsistent with the provisions of articles 15, 16 and 18.”

To create the kingdom for Abdullah, Churchill’s “stroke of the pen” severed Transjordan, roughly three-fourths of Palestine, from the original British mandate established in San Remo in 1920. Churchill and Abdullah subsequently agreed that Transjordan would be accepted into the mandatory area as an Arab country apart from Palestine and that it would not form part of the Jewish national home to be established west of the Jordan River. Abdullah was then appointed Emir of the Transjordania region in April 1921. Britain administered the part west of the Jordan River as Palestine, and the part east of the Jordan as Transjordan.

In August 1922, the British government presented a memorandum to the League of Nations stating that Transjordan would be excluded from all the provisions dealing with Jewish settlement, and this memorandum was approved by the League on August 12. This angered the Zionists because it reduced the area available for a future Jewish state, which they had expected to encompass all of Palestine; that is, both sides of the Jordan River.

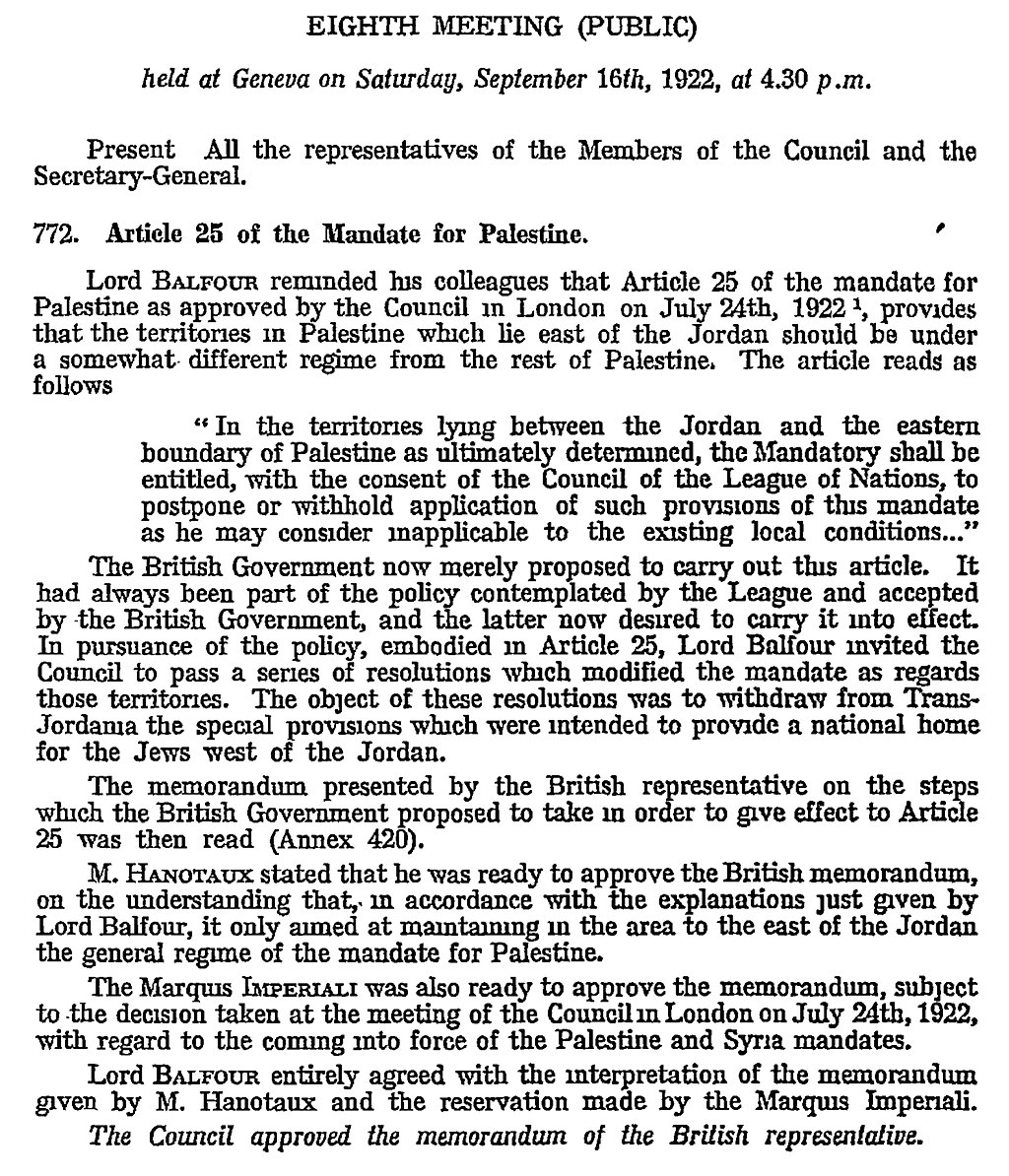

Ironically, it was Lord Arthur Balfour, whose letter to Lord Walter Rothschild in 1917 had promised the Jews a national home in Palestine, who told the League on September 16, 1922, that Britain wished to modify the mandate for the purpose of withdrawing Transjordan from the area intended to provide a national home for the Jews west of the Jordan.

Minutes from discussion of Palestine during the meeting

of the League of Nations (September 16, 1922) - Click graphic to enlarge

Later, the Peel Commission, appointed by the British Government to investigate the cause of the 1936 Arab riots, wrote that at the time of the Balfour Declaration it was understood that the Jewish National Home was to be established in the whole of historic Palestine, including Transjordan.

On June 17, 1946, Transjordan became an independent nation.

When King Abdullah annexed the West Bank in 1948, the country was renamed Jordan.

Sources: Kingdom of Jordan;

Frank Jacobs, “Winston’s Hiccup,” New York Times, (March 6, 2012);

“Emirate of Transjordan,” Wikipedia;

Maurice Ostroff, “The 1967 map is less relevant to Israel's future borders than the 1920 map,” Jerusalem Post, (March 31, 2014).