Libya Virtual Jewish History Tour

By Haïm Z’ew Hirschberg, Robert Attal, Rachel Simon, Rachel Cohen, and Haim Cohen

Early History

Arab-Ottoman Period

Italian Rule

Holocaust Period

The British Occupation

Contemporary Period

Social, Economic, and Religious-Cultural Conditions

Zionist Activity

Attitude Toward Israel

Libya is a country in N. Africa, consisting of the regions of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica (see Cyrene), and Fezzan. Isolated finds of Jewish origin from pre-Exilic Ereẓ Israel were discovered both in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, but there is no reliable evidence of Jewish presence in those regions before the time of Ptolemy Lagos (ruled Egypt 323–282 B.C.E.); he is reported to have settled Jews in the Cyrenean Pentapolis to strengthen his regime there, probably in 312 B.C.E. The phrases used consistently in the sources point to their distribution around Cyrene, presumably as military settlers on royal land. The temporary extension of Ptolemaic control into Tripolitania in the early third century B.C.E. may have occasioned similar Jewish settlement in that area; there are Jewish finds from this date at Busetta and Zliten.

Early History

After the Maccabean breakthrough to Jaffa, commerce between Ereẓ Israel and Cyrene appears to have been strengthened (147–43 B.C.E.). II Maccabees is an abbreviation of a work by Jason of Cyrene. With the political reunion of Egypt and Cyrene under Ptolemy Euergetes II in 145 B.C.E., a fresh wave of Jewish immigration reached the latter country; the Jewish community of Teucheira, evidenced by their epitaphs, and composed probably of military settlers linked with Egypt, must have originated late in the century. In 88 B.C.E., after Cyrene had been freed from Ptolemaic control, the Jews of the country were involved in an undefined civil conflict perhaps to be connected with contemporary manifestations of Greek anti-Jewishness in Alexandria and Antioch. The Roman exploitation of the royal domains at the expense of their cultivators would have involved numerous Jews, ultimately expropriated, perhaps one of the social bases of the risings of 73 and 115 C.E.

Cyrene became a Roman province in 74 B.C.E.; inscriptions of the reigns of Augustus, Tiberius, and Nero at Berenice (Benghazi) indicate a wealthy, well-organized community with an executive board and its own amphitheater for assembly, as well as a synagogue. Jewish urban communities prior to 115 C.E. are further evidenced at Apollonia and Ptolemais. Cyrenean Jewry under Augustus was compelled to defend its right – attacked by Greek cities – to send the half-shekel to Jerusalem, but the Roman power confirmed its privileges.

A section of the Cyrenean community at this point seems to have obtained improved civic status, and Jewish names appear among graduates of city gymnasia both at Cyrene and Ptolemais, but it is clear that the bulk of the community was considered intermediate between alien residents and citizens. Cyrenean Jewry was nevertheless preponderantly rural; sites of Jewish rural settlement are known at Gasr Tarhuna, Al-Bagga, in the Martuba area, at Boreion (Bu-Grada) in the south (the site of an alleged temple

), and at an unlocated place called Kaparodis. The Teucheira group was largely agricultural, and a Jewish rural population probably existed around Benghazi. The occupations of Cyrenean Jewry included, besides agriculture, those of potter, sailor, stonemason, bronze-worker, and possibly weaver. Commercial elements are likely to have existed at the ports of Benghazi, Apollonia, and Ptolemais. The Jewish aristocracies of Benghazi, Ptolemais, and Cyrene were highly Hellenized (cf. a Jew, Eleazar, son of Jason, who held municipal office at Cyrene under Nero); though Jewish graduates of gymnasia appear at Teucheira, most of the Jews there were relatively uncultured and suffered a high rate of child mortality. Cyrenean Jews maintained a synagogue in Jerusalem in the first century C.E.

In 73 C.E., Jonathan the Weaver, a desert prophet

of the Qumran type and a Zealot refugee from Ereẓ Israel, incited the poorer element of the Jews of Cyrene to revolt, leading them to the desert with promises of miraculous deliverance.

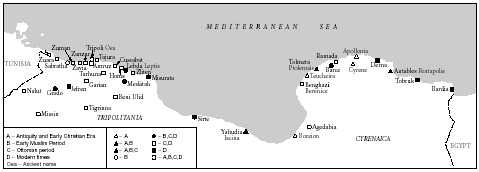

Jewish settlements in Libya, from antiquity to modern times.

Jonathan was apprehended, and his followers were massacred; the Roman governor L. Valerius Catullus also took the opportunity to execute some 3,000 wealthy Jews and to confiscate their property. The Zealot movement was not confined to the city of Cyrene, and the removal of the Hellenized Jewish aristocracy led to the radicalization of the rest of the community. Under Vespasian (69–79 C.E.), the recovery and redistribution of the extensive Cyrenean state lands began, resulting in increased friction with the seminomadic transhumant Libyan elements. To the same period belongs the Jewish settlement of Iscina (Scina) Locus Augusti Iudaeorum (Madinat al-Sultan) on the shore of eastern Tripolitania, an imperial foundation which may plausibly be held to reflect a forcible removal of disaffected Jewish elements from Cyrene to the desert borders – a view which finds support in Jewish historical tradition. A Jewish-Libyan rapprochement on the desert borders may well have taken place prior to the rising of 115.

In 115 – during Trajan’s Second Parthian campaign – the Jewish revolt broke out in Cyrene, Egypt, and Cyprus. The very heavy gentile casualties in Cyrene and the scope of the destruction wrought by the Jews at Cyrene, probably at Apollonia, Balagrae (Zawiyat Beda), Teucheira, and in the eastern areas, suggest that the rebels, under their leader Lucuas (or Andreas), who was called by the gentile historians King of the Jews,

intended to quit the country for good. The wholesale destruction of the Roman temples testifies to the Zealot content of the rising. At the end of 116, the Jews broke into Egypt but were cut off from Alexandria and were defeated by Marcius Turbo; Lucuas is thought to have been killed in Judea.

Jews may have already been living in Ptolemais in the third century, and in the later part of the fourth century, Jewish ships were reaching Cyrene from Egypt. There is much evidence for the existence of a Jewish population in the country on the eve of the Muslim conquest (642), and presumably, the numerous Jewish traditions attached to ancient sites throughout the country relate to the Byzantine period. In Tripolitania, except for the appearance of Iscina, the Jewish record is blank until the fourth century. In Africa, Vetus (Tunisia) Jewish settlement cannot be proven before the early second century C.E., and the Talmud (Men. 110a) seems to imply a gap in Jewish settlement east of Carthage; Jerome nevertheless believed that in the late fourth-century Jewish settlement was continuous from Morocco to Egypt, and numerous place-names on the Tripolitanian coast suggest a very ancient Jewish tradition. A Christian cemetery of the fourth century at Sirte contained chiefly Jewish names, perhaps of people connected with imperial domains of the area. A Jewish community at Oea (now Tripoli), which possessed competent scholars, is attested by Augustine (fifth century). The Boreion community indicates a longstanding settlement; its temple

was converted into a church, and its Jews were forced to accept Christianity by Justinian (527–65). Ibn Khaldūn (14th century) thought the Berbers on Mount Nefusa were Judaized and derived from the Barce area (Cyrene) – like the Jarawa of the Algerian Aurès – but his statement is tentative and the traditions of Judaizing Berber tribes, despite the extensive modern literature concerning them, have been shown not to be pre- or early Islamic.

[Shimon Applebaum]

Arab-Ottoman Period

The Arabs conquered Cyrenaica in 642 and swiftly took the rest of North Africa. They spread Islam among the local populations but allowed members of monotheist religions (referred to as People of the Book (ahl al-kitāb)), namely Christians and Jews, to keep their religion by accepting the status of Protected Peoples (ahl al-dhimmah). According to late Arabic sources, the Jews were dispersed among the Berbers who lived around Mount Nefusa (central Tripolitania) before the Arab conquest, but in Jewish sources, the Jews of this district are only mentioned from the tenth century onward. The Jews also believed that the Jewish population of the entire region originated there. From the frequent repetitions of the surname al-Lebdi in 11th- and 12th-century sources, it can be concluded that there was also an important Jewish population in Lebda, near the harbor town of Homs, and also in the oasis of G(h)adames. There was also a Jewish population in Barce and in other localities. Between 1159 and 1160, the Jewish population suffered as a result of the victory of the Almohads, but the rulers did not take any lives or force conversion.

There is no extant information on Libyan Jewry during the next 400 years. According to a later source, 800 Jewish families fled from Tripoli to Tajurah – situated to the east of the latter – and to Jebel Gharyān (Garian) – in the interior of Tripolitania – as a result of the Spanish invasion of 1510.

Libya was under Ottoman rule between 1551 and 1911, though in the 1711–1835 period, Tripolitania was ruled by the Qaramanlī dynasty, which originated in the Ottoman military and retained nominal allegiance to the Ottoman Empire. Direct Ottoman rule in Libya resumed in 1835. After the Ottoman conquest of 1551, the Jews prospered again. At that time, R. Simeon Labi, a Spanish kabbalist refugee, settled in Tripoli (1549–80) rather than continue to the Land of Israel. He strengthened the position of Judaism and introduced Sephardi traditions of Jewish learning. According to a manuscript which belonged to M. Gaster (now BM Or. 12368), A sad and bitter event happened to the people of the Mahgreb,

i.e., the Jews of Libya were in great distress during the years 1588–89 as a result of the revolt against the Turks which was fomented by the mahdi Yaḥyā b. Yaḥyā. Many of them were forcibly converted to Islam, but with the suppression of the revolt, they returned to Judaism. There is, however, no mention or allusion in Jewish sources to this period of persecution.

The community of Tripoli gained strength with the arrival of Jews from Leghorn (Livorno, referred to as Gornim), most of whom were merchants of Sephardi origin. In Tripoli, in contrast to some other Mediterranean cities, the Gornim did not constitute a separate congregation due to their relatively small number, but many of them were of a higher socio-economic level, with strong commercial, social, and familial ties across the Mediterranean. In 1663, the Shabbateanleaders

). These were the temporal leaders of the community and belonged to a small number of wealthy families with strong ties to the Muslim authorities.

Purim of ash-Sharif

on 23 Tevet commemorates this event, about which R. Shabtai Tayyar wrote a poem, Mi Kamokha. During the famine and plague of 1784–85, there was much suffering among the Jews, and they were threatened with grave danger when Ali Gurzi, known as Burgul,

was appointed pasha of Libya. After a year and a half, he was banished from the town, and in commemoration of their deliverance, the Jews of Tripoli celebrate Purim of Burgul

every 29 Tevet. R. Avraham Khalfon wrote another Mi Kamokha poem in honor of this event.

Jewish quarter

) in Tigrinna contained about 300 Jews. They earned their living as goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and peddlers among the Bedouin in the area.

In the mid-19th century, the traveler Benjamin the Second (Israel Benjamin) found about 1,000 Jewish families (about a third of the population) in Tripoli. There were four competent dayyanim and eight synagogues. In 1906, N. Slouschz visited Libya, and his descriptions have become a historical source of information. Most of the information in his books about the 18th and 19th centuries stems from his guide Mordecai Hacohen, whose history was based on earlier sources and includes numerous observations on the current conditions of the Jews in the urban centers and the rural hinterland.

At the end of Ottoman rule, there were no important incidents in the history of Libyan Jewry, apart from the fact that in 1909 they, like all citizens of the Ottoman Empire, were subject to the compulsory military service law. Jews – of an Orthodox religious background – feared that they would be forced to desecrate the Sabbath and other religious holy days and eat non-kosher food in the course of military service. However, the law was only in force for a short time since Libya shortly thereafter fell to the Italians, and the Ottoman command respected Jewish religious restrictions. The Jews even benefited from the military training that some 260 of their young men had received since the latter could protect the community in the interim period between the fall of the Ottoman regime and the complete Italian occupation of Tripoli when the town suffered from attacks by Arab rioters.

[Haïm Z’ew Hirschberg /

Rachel Simon (2nd ed.)]

Italian Rule

On October 11, 1911, Tripoli fell to the Italians, who, within two months, took the rest of the Mediterranean coastal urban centers of Libya. Most of Tripolitania was also conquered within the next two years, but the Sanusi resistance prevented the conquest of most of Cyrenaica. During World War I, most of the hinterland was regained by the Arab and Berber resistance with the help of the Ottoman and German military.

Following World War I, Tripolitania was retaken by the Italians, but internal Cyrenaica was fully conquered only by the early 1930s when the Sanusi-led opposition was crushed. Although there were Jewish communities in the Tripolitanian and Cyrenaican hinterland, most of the Jews were under Italian rule from late 1911. The first 25 years of Italian rule passed peacefully for the Jews as far as Italian treatment of Jews was concerned. They retained equal rights, and the number of those in government employment grew, as did the numbers of those who became prosperous and attended urban Italian state schools. During this period, Zionist activity went unhindered.

The Jewish population of Libya in 1931 was 21,000 (4% of the total population). They were dispersed in 15 localities, with about 15,000 of them in Tripoli. In 1936, the Italians began to enforce fascist legislation, especially in Tripoli, where most of the trade was in Jewish hands. This legislation aimed at modernizing social and economic structures, similar to the then-current conditions in Italy. The authorities started to hinder the freedom of the Jews, who were forced to open their shops on the Sabbath, and those who refused to do so were punished, imprisoned, and some even whipped in public. With the implementation of anti-Jewish racial legislation in late 1938, Jews were removed from municipal councils, some were sent away from government schools, and their papers were stamped with the words Jewish race.

[Haim J. Cohen /

Rachel Simon (2nd ed.)]

Holocaust Period

When the Benghazi area fell to the British on February 6, 1941, the Jews were overjoyed over their deliverance and their meeting with Jewish Palestinian soldiers serving in the British army. This did not last long, and on April 3, 1941, when the city was recaptured by the Italians, young Arabs assaulted the Jews of Benghazi. The British reoccupied Benghazi briefly on December 24, 1941, and this time the Jews were much more careful regarding their contacts with the British army. The January 27, 1942, reoccupation of Benghazi by Axis forces was followed by the systematic plunder of all Jewish shops and the promulgation of a deportation order: 2,600 persons were deported into the desert to Giado, 149 mi. (240 km.) south of Tripoli, where they lived under extremely harsh conditions. During their 14-month exile, 562 people died of starvation or typhus. In March 1941, the Italian governor of Tripoli took discriminatory measures against all Jews and ordered Jewish organizations to cease all activities. In April 1942, the Jews of Tripoli were compelled to declare all their property, and those between 18 and 45 years of age were sent to forced labor: some 1,400 persons to Homs and 350 to lay the railway line linking Libya and Egypt. They, together with the rest of the population of Tripoli, were subject to severe bombing by the Royal Air Force. Jews with French and British nationality were declared enemy nationals

[Robert Attal /

Rachel Simon (2nd ed.)]

During this period, Zionist activity was paralyzed. In general the relations with the Muslim population did not worsen, and village Muslims sometimes gave sanctuary and shelter during the three years to Jews who fled to them, although in the towns fascist propaganda reached and influenced the young Muslims. During World War II the men of the Jewish Brigade conducted various political and cultural activities among the Jewish population. The Jewish Palestinian soldiers were greatly impressed by the knowledge of Hebrew among Libyan Jews and their Zionist aspirations. Although there was not much Jewish immigration to Palestine prior to the late 1940s, and the community as a whole was pro-Italian, the events of World War II and the 1945 riots in Tripoli and its vicinity changed the political attitude of the Jews: they did not trust Italy anymore and feared for their life and property under independent Arab rule. This resulted in the mass immigration to Israel of some 95% of the community within three years (1949–51).

The British Occupation

During the British occupation (1942/43–51), the Jews were able to reopen their schools, although, in this period, they suffered from persecution by Muslims, which was unparalleled in the past. On November 4, 1945, there were Muslim riots against the Jews of Tripoli and neighboring towns. In Tripoli, the masses ran wild, killing and wounding many Jews, looting their property, and setting fire to five synagogues. On November 6, troublemakers from Tripoli arrived in Zanzur (c. 30 mi. (48 km.) from Tripoli) and incited the Muslim population against the 150 local Jews, of whom half were murdered. Jews were also killed at Meslātah, Zawiyah, Tajurah (10 mi. (16 km.) from Tripoli) and at Amruz (2½ mi. (4 km.) from Tripoli). According to various estimates, from 121 to 187 Jews were killed, and many were wounded during these incidents. Nine synagogues were burned down, and damage to property was half a million pounds sterling, a very large sum for a poor community. The British authorities did not succeed in immediately stopping the excesses because they had Arab soldiers and policemen in their service who generally joined in the riots with the masses when sent to protect Jews; only when forces came from outside, especially Sudanese soldiers, were the rioters dispersed. After the riots, about 300 rioters were brought to trial, of whom two were sentenced to death. The leniency of the sentences and the incitement by the Arab countries regarding Palestine encouraged Libyan Muslims to persecute the Jews again in June 1948 in Benghazi and Tripoli. However, this time some of the Jews were ready to defend themselves since after the 1945 attacks, a Jewish defense organization with members of both genders was set up in Tripoli by an emissary from Palestine (1946). Tripoli Jews used hand grenades and repelled marauders trying to enter the Jewish quarter; before the rioters could be stopped, the police arrived, but 14 Jews had already been killed. Most of the rioters were Tunisian volunteers on the way to the Palestinian front.

Contemporary Period

After the 1945 riots, Jews began leaving Libya, most of them immigrating to Palestine. Between 1919 and 1948, about 450 Jews immigrated to Palestine from Libya, most of them during the years 1946 and 1947, when about 150 immigrated there. When the State of Israel was established, Jewish flight from Libya increased; they left by way of Tripoli and Tunisia; Between May 1948 and January 1949, about 2,500 left the country. Only in February 1949 did the British permit legal immigration to Israel, and many immediately registered to emigrate.

Several officials of the Jewish Agency and Israeli government ministries operated legally in Tripoli and traveled throughout the country. These few Israelis were assisted by numerous indigenous Jews and, in collaboration with the local authorities, prepared the required travel documents. Because the disease was widespread among Libyan Jews, medical personnel of the OSE health organization and Israel checked prospective emigrants and treated those who were forbidden to enter Israel prior to recovery.

During the mass emigration, most Libyan Jews traveled directly from Tripoli to Haifa in Israeli ships. Israeli officials were also involved in cultural events and teachers’ training in Tripoli and its vicinity. Until the end of 1951, some 30,000 Jews emigrated, and only about 8,000 Jews remained in Libya. Most of them lived in Tripoli and about 400 in Benghazi, while the townlets and villages were almost entirely emptied of Jews.

Under the independent Libyan regime (from December 24, 1951), Jews did not suffer from persecution, and equal rights were guaranteed to them under the Libyan constitution. Nevertheless, Libyan citizens were forbidden to return home if they visited Israel (June 1952), and in 1953 the authorities closed the Maccabi Club. In June 1967, after the Six-Day War, there were anti-Jewish riots, and the Jews locked themselves inside their houses for fear of attack; 17 Jews were murdered, and many were arrested. After a time, the majority of the remainder left, mostly to Italy and to Israel. Following the coup by Col. Muammar Gaddafi on September 1, 1969, the 400–500 Jews remaining in Libya were concentrated in a camp in Tripoli. These included Libyan citizens, bearers of foreign citizenship (British, French, Italian), and those bearing no citizenship. The government claimed that this step was taken to defend the Jews against incursions on their property. After the coup, Jews were not allowed to leave Libya, although ultimately, all of them were released, and some of them succeeded in leaving Libya. On July 21, 1970, the revolutionary regime announced the nationalization of Italian and Jewish property, mostly of Jews who had left Libya indefinitely.

Social, Economic, and Religious-Cultural Conditions

Demographically, it should be noted that Libyan Jews, of whom there were about 20,000 in 1911, were mainly concentrated in the town of Tripoli (c. 12,000), but many were scattered in towns, townlets, and villages all over the country. According to the 1931 census, there were 24,534 Jews, and in 1948 about 38,000 Jews in Libya, of whom about 20,000 were in Tripoli. This shows that there was no mass emigration before 1948, nor was there considerable migration within the country. At the end of 1970, only some 90 Jews remained in Libya.

Until the late 19th century, Libyan Jews spoke mostly a Jewish dialect of Maghrebi Arabic, which included Hebrew words. Because Muslim neighbors usually understood the local Judeo-Arabic, Jewish peddlers often used a unique argot among themselves when doing business with Muslims. Jewish communities in Libya, as elsewhere in the Jewish world, made sure that boys received formal education in community schools enabling them to read the Bible and prayer books. Studies in these schools consisted of learning the Hebrew alphabet and reciting Hebrew and Aramaic texts. Since the spoken language was Judeo-Arabic, most Jewish men did not understand what they recited nor the readings from the Bible, the Zohar, and other Holy Scriptures at the synagogue which they attended on the evenings or the Sabbath; most of them could not write either. The community did not offer any formal education to Jewish girls.

The wide dispersal of Libyan Jewry into dozens of communities, many comprising only a few families, sometimes affected their economic and educational circumstances. With the opening of Christian schools in Tripoli in the 19th century, several Jewish boys and girls, especially those from families with commercial and social ties with Europe, attended these schools. The religious leaders of the community, but even wealthy families with ties to Europe, preferred their children to receive a Jewish education. This prompted Jewish merchants from Tripoli to initiate the opening of an Italian school in Tripoli in 1876, which Italian Jews ran. This school, which accepted girls from 1877, taught secular subjects, focusing on Italian culture, but included also Hebrew and Jewish subjects.

The Alliance Israélite Universelle opened a school only in Tripoli (in 1890 for boys and in 1896 for girls), with emphasis on French culture and secular subjects, as well as Hebrew and Jewish subjects. In both the Italian and Alliance schools, the Jewish subjects were taught by indigenous teachers who usually did not receive any pedagogic training, while the secular subjects were taught by Italian formally trained teachers and Paris-trained Alliance teachers from France, the Ottoman Empire, and North Africa. Under Italian rule, Italian state schools were established in Libya, and many Jews preferred to send their children there, mainly in Tripoli and Benghazi; in many small towns, they made do with studying at a heder. For this reason, a large proportion of Jewish children outside the main towns received no modern education, and girls had no formal education whatsoever. However, in comparison to the beginning of the century, the younger generation contained far fewer illiterates. The Jews also opened a private high school in Tripoli in 1936, when they were expelled from Italian high schools for refusing to attend school on the Sabbath, but they were forced to close it in 1939.

As a result of the anti-Jewish racial legislation of 1938, Jews could not attend state schools and tried to organize communal education for boys. Following the British occupation (1942/43), Jewish communal education was resumed, and the Jewish Palestinian soldiers in the British army helped the communities of Benghazi and Tripoli to establish schools for boys and girls with a curriculum based on Jewish education in Palestine. Jewish soldiers participated in the teaching and in teacher training for those schools. Many of the teachers in the Tripoli school were previous members of the Ben-Yehudah Society. In 1947, a Hebrew teachers’ seminary was opened in Tripoli with the help of educators from Palestine. It trained teachers for the Hebrew school in Tripoli and later also for the vicinity, but it closed down after the mass emigration.

Libya’s most prominent rabbis included R. Masʿud Hai Rakaḥ, author of the work Ma’aseh Roke’aḥ on Maimonides; R. Abraham Ḥayyim Adadi, author of Va-Yikra Avraham; and R. Isaac Hai Bukhbaza (d. 1930).

Apart from the Tripoli community, which contained a number of important merchants and officials, most Libyan Jews were occupied as artisans; a few were peddlers and farmers and thus worked hard for their living. Peddlers often traveled alone in the countryside for lengthy periods of time, in some instances returning home only for the High Holidays and Passover. Despite the strict segregation between non-kin men and women in Libya, Jewish peddlers could trade directly with Muslim women, and they usually felt safe among the Muslim nomads and rural population. The statements of 6,080 breadwinners who immigrated to Israel from Libya between 1948 and 1951 show that 15.4% were merchants, 7.5% were clerks and administrators, 3.0% were members of the liberal professions (including teachers and rabbis), 6.1% were farmers, 47% were artisans, and 7.1% were construction and transport workers. The remainder (13.9%) worked in personal services or were unskilled laborers.

As a result of their poverty, disease was widespread among Libyan Jewry; they suffered mainly from trachoma, tuberculosis, and eczema, so much so that children in school had to be classified according to illness. Following the inception of legal Jewish immigration to Israel, the OSE began work in Tripoli in 1949 to care for schoolchildren and convalescents who were sent to a talmud torah in the town, where healthy children were kept. However, in April 1950, only 30% of the 2,000 Jewish schoolchildren were healthy; thus, the Israeli immigration authorities had to screen potential immigrants for illness and provide them with medical care before permitting them to immigrate.

Zionist Activity

By the turn of the 19th century, news about the Zionist organization had reached Libyan Jews, and several members of the communities of Tripoli and Benghazi tried to establish local Zionist branches. Correspondence kept in the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem includes letters sent from Libya between 1900 and 1904 acknowledging the receipt of Zionist publications in Hebrew, French, and Ladino. The authors of these letters were ready to organize Zionist activities and collect dues (shekel) for the Zionist organization, and they even sent some dues that they had collected. One letter, in particular, demonstrates excitement regarding the Zionist idea and readiness to get involved in Zionist activities. It seems, though, that these letters remained mainly unanswered.

A short time after Italy conquered Libya, contact was made between Libyan Jewry and the Italian Zionist Organization, mainly due to the newspapers that reached Libya. In 1913 some of the readers of these newspapers, led by Elijah Nehaisi (1890–1918) of Tripoli, tried to found a Zionist organization. At first, only an evening talmud torah was founded (1914) in order to spread the Hebrew language, and then the Zion Society was established (May 1916), and the committee of this Zionist association succeeded in entering the Tripoli community committee, gaining 11 of the 31 places as members of their association (June 1916). The Zion Society published the first Zionist newspaper in Libya, Degel Ẓiyyon (1920–24). In 1923, the association changed its name to the Tripolitanian Zionist Federation. The Ben Yehuda Association, established in 1931, was very active in spreading the Hebrew language in Tripoli. In 1933, it published a weekly entitled Limdu ’Ivrit! (Learn Hebrew!

). The association also opened a Hebrew school in Tripoli, ha-Tiqvah, in 1931 for adults and children of both genders, which was attended by 512 pupils (1933); their numbers rose to 1,200 in 1938/39. All the teachers in this school were indigenous self-taught Jews of both genders, and several pupils became teachers as well. This nucleus of teachers was very active in education following the British occupation. In 1939, the school was closed, and the association disbanded on government orders as part of the anti-Jewish racial legislation.

When Libya was conquered by the British (November 1942–January 1943) and Jewish Palestinian soldiers came to the country, Zionist work was resumed. A number of Zionist youth organizations were established with the initial help of emissaries from Palestine, and several Hebrew newspapers were published (Ḥayyeinu, a Hebrew monthly, 1944; Niẓẓanim, Hebrew monthly, 1945–48; Ḥayyeinu, Hebrew, Italian, and Arabic weekly, 1949–50). In 1943, the He-Ḥalutz (the Pioneer

) organization for youth movement graduates was set up, and an agricultural training farm (hakhsharah) was established near Tripoli; it was abandoned in November 1945 when the anti-Jewish riots broke out; The ten trainees immigrated to Israel (1946). Subsequently, agricultural training was renewed until the 23 trainees were forced to abandon the farm during the June 1948 pogroms.

In May 1946, an emissary from Ereẓ Israel founded a defense organization in Tripoli, which was trained in the use of weapons and manufactured homemade bombs; it defended the Jewish quarter in Tripoli during the June 1948 riots. In 1946, illegal immigration to Ereẓ Israel also began, achieved by illegally crossing the frontier into Tunisia and from there to Marseilles. In 1948, illegal immigration to Ereẓ Israel was organized through Italy. Hundreds emigrated in this way until legal immigration became possible (February 1949).

Since Libyan Jews were observant, most of the Zionist organizations were religious, including the youth groups founded after 1943. These were later affiliated to Ha-Po’el ha-Mizraḥi.

[Haim J. Cohen /

Rachel Simon (2nd ed.)]

Attitude Toward Israel

When the UN General Assembly resolved (November 21, 1949) that Libya become independent before January 1, 1952, Israel, itself a newcomer to the UN, cast its vote for the resolution. This gesture of goodwill received no reciprocation, and Israel did not repeat it in the case of any other Arab state. Anti-Jewish outbursts accompanied the announcement about the impending independence, and Israel took all precautions to enable Libya’s Jews who wanted to settle in Israel to reach their destination before the critical date. Close to 90% of Libyan Jewry settled in Israel up to the end of 1951.

Independent Libya joined the Arab League in March 1953 and adopted a hostile attitude toward Israel, though it was mainly declaratory. Libya took part in Arab summit conferences, joined the Arab boycott against Israel, conducted anti-Israel propaganda, and attacked Israel at the UN. The situation became more critical during the Six-Day War (1967), when widespread strikes of Libyan oil workers, as an expression of Arab solidarity, brought the flow of oil to a temporary stop, hitting the U.S. and Western Europe, which allegedly aided Israel and shaking the conservative rule of King Idrīs.

After the war, Libya allowed Palestinians to live and work inside its territory, but only in limited numbers. It permitted collections for Palestinian organizations, founded a school for al-Fatḥ orphans, and played host to several delegations from these organizations. Libya, like other Arab oil states (Saudi Arabia and Kuwait), contributed an annual share ($8,000,000) to Egypt and Jordan, according to the resolution of the 1967 Arab summit conference in Khartoum.

A drastic change occurred in Libya’s attitude toward Israel after the overthrow of the monarchy on September 1, 1969, and the rise of a revolutionary regime. Libya now adopted the militant line of the extreme Arab states in regard to Israel, as well as against the West in general. Muammar Gaddafi, chairman of the Revolutionary Council, announced from the start that the new regime opposed political solutions to the Israel-Arab conflict and did not believe in the possibility of a successful peaceful settlement. He promised to mobilize all of Libya’s rich resources to assist the armed confrontation with Israel. At the Arab summit conference in Rabat (December 21–23, 1969), he also promised to extend a considerable part of Libya’s oil revenues (which amounted to $1,000,000,000 annually) to reinforce the Arab front. Libya set up a holy war fund

out of state grants, special taxes, and individual donations.

The following meeting in Tripoli (December 25–27, 1969) of the presidents of Egypt, Sudan, and Libya, who agreed to establish an alignment of the three countries, underscored the new regime’s desire to join the Arab struggle against Israel. Libya drifted more and more into the sphere of influence of Nasser, who exploited the situation to deepen the Egyptian military and economic penetration into Libya, a step which became possible after the liquidation of the American and British military bases there and the expulsion of foreigners in 1970. The regime acquired considerable quantities of arms that could serve the Arab cause at the front. On November 8, 1970, the presidents of Libya, Egypt, and Sudan decided to establish a union,

or federation, of their countries to bring about closer military, economic, and political links; in 1971, Syria joined this bloc. Nonetheless, these and other attempts at political-military union proved futile. Libya assisted the Palestine organizations financially and politically.

Following the anti-Jewish riots that broke out in Tripoli in June 1967, in which some 20 Jews were killed and Jewish property was set on fire, an almost complete emigration of the 3,500 Jews in Libya took place. Only 200 to 300 remained in 1969, 90 in 1970, and a mere handful in 1972; there were no Jews left in Libya by the end of the 20th century. There were thus hardly any Jews left in the country when King Idrīs was deposed, and the republic was proclaimed in September 1969, headed by Col. al-Gaddafi, who became the most radical and extreme of the anti-Israel, anti-Zionist Arab leaders.

A few days after the proclamation of the republic, an edict was issued authorizing the government to sequestrate the assets and property of Jews who had left the country. This edict was made law in February 1970, but in view of its blatant anti-Jewish nature, it was suspended and replaced in May by another law which provided for the sequestration and transfer to an official custodian of the property of persons whose names were handed in by the Ministry of Interior. In an appendix not mentioned in the law itself, 620 names were given, 605 of whom were known to be Jewish.

In July 1970, however, the Libyan government undertook, by a special law, compensation for the confiscated property. According to this law, special government committees were to determine the value of the property, and compensation would be paid through government bonds redeemable in 15 years. There is no information on whether any such bonds were received, and it is probable that its purpose was merely to give legal sanction to the expropriation of Jewish property.

Following the visit of President Anwar Sadat to Jerusalem in November 1977, Libya joined the Rejection Front of the Arab States, which opposed any negotiations with Israel.

Since Gaddafi was killed on October 20, 2011, Libya has been in chaos, with warring factions seeking to fill the vacuum. An interim government was formed in 2021. Mohamed al-Menfi, a former ambassador to Greece, became head of the Presidential Council, and Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, a businessman, was named Prime Minister.

In August 2023, after decades of hostility, the possibility of a breakthrough in relations occurred when Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen met his Libyan counterpart Najla Mangoush in Rome. Cohen said, “I spoke with the foreign minister about the great potential for the two countries from their relations” and the importance of preserving Jewish heritage in Libya.

A Libyan official told the Associated Press the meeting followed U.S. efforts to encourage Libya to normalize relations with Israel during a visit to Tripoli by CIA Director William Burns.

Ben Fishman, former director for North Africa on the National Security Council, said, “Dabaiba likely viewed outreach to Cohen as a signal to the United States that he is forward-leaning on engagement with Israel, despite his country being historically supportive of the Palestinian cause. Similarly, when he faced political pressure at home late last year, he answered Washington’s long-desired request to arrest and extradite Pan Am 103 suspect Abu Agila Masud, after which he endured protests and accusations of legal overreach.”

The possibility for rapprochement was set back, however, when Israel publicly disclosed the meeting. Israel insisted it had been approved by Libya “at the highest levels,” and a Libyan official told AP that Mangoush briefed the prime minister when she returned to Tripoli.

Nevertheless, widespread rioting in Libya followed the publicity of the meeting. Mangoush was initially suspended and then fired. She reportedly fled to Turkey due to threats on her life.

Libya’s Foreign Ministry subsequently insisted the meeting was “unplanned and incidental” and that Libya rejects normalization with Israel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

EARLY PERIOD: P. Monceaux, in: REJ, 44 (1902), 1ff.; N. Slouschz, Travels in North Africa (1927); S.A. Applebaum, Yehudim vi-Yevanim be-Kirene ha-Kedumah (1969); Hirsch-berg, in: Journal of African History, 4 (1963), 313ff.; Zion, 19 (1954), 52–56 (a bibl.). MODERN PERIOD: R. De Felice, Jews in an Arab Land: Libya, 1835–1970 (tr. from Italian by Judith Roumani, 1985); F. Suarez et al. (eds.), Yahadut Luv (1960); I.M. Toledano, Ner ha-Ma’arav (1921), 88; I.S. Bernstein, in: Sinai, 19–20 (1946–47); G. Scholem, Iggeret Avraham Mikha’el Cardozo le-Dayyanei Izmir (1954); Hirschberg, Afrikah, 1 (1965), 5–17, 11, 173–206; idem, in Bar-Ilan, 4–5 (1967), 415–79; R. Attal, in: Sefunot, 9 (1965), a bibl.; I.J. Benjamin, Acht Jahre in Asien und Afrika (18582), 230–7; M. Cohen, Gli ebrei in Libia, usi e costumi (1928); M. Eisenbeth, Les Juifs de l’Afrique du Nord (1936); G.V. Raccah, in: Israel, 23 (Florence, 1938); S. Groussard, Pogrom (1948); R. Attal, Les Juifs d’Afrique du Nord – Bibliographie (1975); H.Y. Cohen, Asian and African Jews in the Middle East – 1860–1971; Annotated Bibliography (1976). HOLOCAUST PERIOD: Rabinowitz, in: Menorah Journal, 23 (1945), 115–26; E. Kolb, Bergen-Belsen (Ger., 1962), 64; P. Juarez et al. (eds.), Yahadut Luv (1960), 197–201. ADD. BIBLIOGRAPHY: R. Simon, Change Within Tradition among Jewish Women in Libya (1992); idem, “The Socio-Economic Role of the Tripolitanian Jews in the Late Ottoman Period,” in: M. Abitbol (ed.), Communautés juives des marges sahariennes du Maghreb (1982), 321–28; idem, “The Relations of the Jewish Community of Libya with Europe in the Late Ottoman Period,” in: J.-L. Miège (de.), Les relations inter-communautaires juives en Mediterranée occidentale XIIIe–XXe siècles (1984), 70–78; idem, “Jews and the Modernization of Ottoman Libya,” in: The Alliance Review, 24 (1984), 33–40; idem, “It Could have Happened There: The Jews of Libya during the Second World War,” in: Africana Journal, 16 (1994), 391–422; idem, “Jewish Participation in the Reforms in Libya during the Second Ottoman Period, 1835–1911,” in: A. Levy (ed.), The Jews of the Ottoman Empire (1993), 485–506; idem, “Language Change and Political-Social Transformation: The Case of the Libyan Jews (19th–20th Centuries),” in: Jewish History, 4 (1989), 101–21; idem, “Jewish Female Education in the Ottoman Empire, 1840–1914,” in: A. Levy (ed.), Jews, Turks, Ottomans: A Shared History, Fifteenth through the Twentieth Century (2002), 127–52; idem, “Shlichim from Palestine in Libya,” Jewish Political Studies Review, 9 (1997), 33–57; idem, “Education,” in: R.S. Simon, M.M. Laskier, and S. Reguer (eds.), Jews in the Modern Middle East and North Africa (2002), 142–64; idem, “Zionism,” in: ibid., 165–79; H.E. Goldberg, “Ecologic and Demographic Aspects of Rural Tripolitanian Jewry, 1853–1949,” in IJMES, 2 (1971), 245–65; idem, Cave Dwellers and Citrus Growers: A Jewish Community in Libya and Israel (1972); idem, “Rites and Riots: The Tripolitanian Pogroms of 1945,” in: Plural Societies, 17 (1978), 75–87; idem, “Language and Culture of the Jews of Tripolitania: A Preliminary View,” in: Mediterranean Language Review, 1 (1983), 85–102; idem, Jewish Life in Muslim Libya: Rivals and Relatives (1990); idem, “Libya,” in: R.S. Simon, M.M. Laskier, and S. Reguer (eds.), ibid., 431–43; H.E. Goldberg and C. Segré, “Mixtures of Diverse Substances: Education and the Hebrew Language among the Jews of Libya, 1875–1951,” in: S. Fishbane, J.N. Lightstone, and V. Levin (eds.), Social Scientific Study of Judaism and Jewish Society (1990), 151–201; The Book of Mordecai: A Study of the Jews of Libya, trans., ed., and annotated by H.E. Goldberg (1993); M.M. Roumani, “Zionism and Social Change in Libya at the Turn of the Century,” in: Studies in Zionism, 8:1 (1987), 1–24.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

“Libya,” Wikipedia.

Lauren Marcus, “Libyan FM flees for her life after meeting with Israeli counterpart,” World Israel News, (August 28, 2023).

David Israel, “Libyan Foreign Minister Suspended, Exiled, following Meeting with Israeli Counterpart,” Jewish Press, (August 28, 2023).

Jonathan Lis, “After Libya Fiasco, Netanyahu Instructs: No Secret Diplomatic Meetings Without My Green Light,” Haaretz, (August 29, 2023).

Ben Fishman, “The Rise and Immediate Fall of Israel-Libya Relations,” Washington Institute, (August 29, 2023).